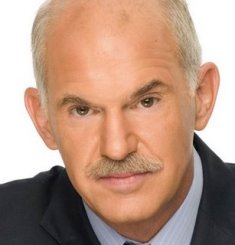

Optimistic after negotiating an emergency bailout deal with fellow E.U. member states, Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou sat down with TIME contributor Nicole Itano in his office at the Maximos Mansion in Athens this week. Highlights:

How much did you know about the situation Greece was in before you came to office? How big a surprise was this crisis to you?

That then translated into the economy — how we use money, whether we invested it correctly, whether we invested it in the wrong things, whether we just wasted it, whether it was lost through lack of transparency. And that just created the whole problem of the huge deficit and the huge debt. So putting our house in order is actually reshaping and re-launching Greece, but reshaping the whole political system. In many ways this crisis should be seen also as an opportunity.

When this crisis began you talked a lot about these larger issues, tackling corruption and tax evasion. And then there was this demand from the markets for immediate cuts. Did that force you to abandon efforts on some of the bigger structural changes?

What the markets were saying is we’ve heard this, we don’t believe you. Greece has lost its credibility. What I was saying all along is we have to bring back our credibility. That did in fact work. Credibility for Greece has come back. Of course, those are short-term changes. We have to get down to the deeper changes, which we’re already doing. So that’s this phase. Now getting beyond this immediate crisis — getting a breathing space to actually get down to the deeper — and I would say even more creative changes, in our society. (See TIME’s Greece covers.)

Is it Greeks who are expecting this change or the international community?

Both, I think. First of all, the international community because in a sense in the European Union we have become a test case of both the euro — its survival — and how to deal with this high deficit in a time of crisis. It’s not only a Greek problem. Our bad ways, if you like, or our difficulties or our wrong decisions, have exacerbated the problem of the international crisis in Greece. (Read: “Germany: Tensions at the Top.”)

So how do you deal with this? In fact, I think you’ll see in these crises two different types of political responses. One, which I would say is a more polarizing and more populist and even scapegoating kind of leadership role. And one which says, no, lets get down to the real issues, lets work together, lets be more collective in our response. Let’s be more democratic in our response.

You are the third Papandreou to hold this office. In style, you are a very different leader from your father and grandfather. Your father was a very populist leader in many ways. Is that difference just reflective of your different personalities? Or is it also that it’s a different time?

Every leader wants to put his or her imprint on the work that they do, and grow up in specific eras. I think there is a heritage which I’m proud of, which is a fight for democracy, a fight for social justice, a fight for freedom. My grandfather went to jail or exile six times in his life, fighting for his principles for democracy, or for his country. And my father twice. One of the reasons he went to the United States was that it there was a dictatorship in Greece. He was beaten up or tortured and then left. And then again during the dictatorship, all of us left Greece. That gives me a sense, when you go through a crisis, that I’m not the only one. There are generations that have been through even worse situations. And they’ve been able to survive and continue believing in their goals and in their dreams.

People call you a decent man. But politics is not always a decent game. In the right and tumble world of Greek politics, is decency an effective political strategy?

I’ve been in politics for quite a few years, it’s getting close to 28 to 29 years. So the fact that they call me decent after 29 years shows you can be decent in politics. There is this concept of politics as a dirty game. It’s a difficult game, but it doesn’t have to be dirty. I think this is what we need to bring to politics. I think politics around the world has very often been captured by big interests — lobbies they call them in the States. (See how Americans are spending now.)

So sometimes people also have unrealistic expectations of what their state or their democracy can provide. The Greeks of today or tomorrow, can they expect the same social support, the same social welfare state that the generations before them expected? Or are Greeks going to have to recalibrate their expectations?

We want to make sure the social system survives. We have to become competitive. Greece also has both negatives, but also a positive on this because our social system is not well organized, there’s a lot of waste. So in cutting down the waste, I think we can modernize it and make it even more efficient as far as costs. And this is where I think we can move ahead. There are countries that have been able to maintain a social welfare system, and see that as part and parcel of being competitive. That is the Nordic countries, or the Scandinavian countries, where they have a very important welfare system, but they’re at the top, most competitive countries in the world. I often like to say that the sense of welfare and security that a person needs, sometimes also helps in making that person more innovative, more risk taking, more entrepreneurial. (See pictures of the global financial crisis.)

Is that the model you’re looking at for Greece, the Nordic model?

I would say the Nordic model, of course with its Mediterranean dimension. Of course, we have a different cultural style, I think a more anarchistic kind of character. If you free that, in a well-defined framework, that can become a very innovative force.

But in Norway or Sweden, people have faith in the state, they have faith that the state functions. How do rebuild that faith — or perhaps build it in the first place. It’s easy to say you want to end corruption, but how do you actually change that political culture?

The first thing is to realize that it exists as a problem and that we’ve accomplished already. People are saying: ‘we do need this change. We do want to have a different state. We do want to fight corruption.’ How do you do that? I think here we don’t have to invent the wheel. For example, there are some things we can do which modern technology allows us to do, which makes things much easier. For example: putting every single signature of a public servant, from a minister to the local civil servant on the web, so that people can see where their money goes and what the decisions are. (See the 50 best websites of 2009.)

More checks and balances. Our budget is going to be under the scrutiny of the parliament, but also an independent body. More meritocracy in the public service. We now have a system where people will be chosen only on a meritocratic basis, not a clientelistic basis. This is slowly changing things.

Also, decentralizing this huge central government to regional and local government so that services are provided at a local level, but decisions are also made a local level, which makes it more accountable. When I was Minister of Education, for example, I would sign the leave of absence of the driver of a dean of a university. So if he had to take his holidays, I would have to sign that. This is crazy. This is micromanagement. But the reason that existed was that one hand people thought that was control, and that comes from a legacy of authoritarianism and dictatorship and so on, so a lot of power at the center of the state. But it also becomes easily clientelistic. You have to come to me for the smallest of favors. And then I’ve got your vote. And then I’ve been able to influence you. That’s what we’re changing.

Some people are going to resist giving up that power. I imagine people even in your own party. Are you willing to take those people on? Are you willing to root out corruption within your own party?

I said the first thing we have to do is change ourselves. We have to be the example, if you like, and lead by example in many ways. And this is what I did when I took on the party, took the leadership of the party. I said okay, the first thing we have to do is change. As a matter of fact, one of our slogans is “We’re changing ourselves to change Greece.” I think this is what we’ve been able to do. It’s not an easy process, but that’s the only way we can do this. (Read: “Greek Austerity Measures Spark Rising Protests.”)

Talking to people on the streets, one thing I heard again and again is that people want to see somebody punished for corruption and tax evasion. What is your response to that? Will people see punishment?

I get that all the time. This is the sense that I was telling you, that people feel that you do not have the rule of law, but the law of the powerful. So that’s what we have to change around, so it’s not as if simply because you’ve got money or simply because you have some high position somewhere you can do anything you want. We’re actually moving ahead on this. This is a central theme. We want to do this through democratic methods. We want to strengthen our democratic institutions. What has happened is they’ve been weakened by this clientelism.

Do you think your experience, having been born in America, raised in America and lived in Sweden, seen other forms of government in action, has that shaped or impacted your own expectations or ideas of what is possible in Greece?

First of all, I think this is an experience that lots of Greeks have. There are lots of Greeks in the diaspora, lots of Greeks in the United States. (See pictures of immigration in Europe.)

Sometimes, migration or living in different cultures can either make you a bit claustrophobic or defensive about your identity — and I think we may all go through that phase when we are in that migratory period — but it also can let you open up and let you feel happy about the fact that you have these different inputs and different cultures that you can use as resources. But this mixture of cultures I think also has, for me, done one more thing. You can see that Greeks in the diaspora have been very successful. I think one thing one can say is that it’s not in our DNA, it’s not even in our cultural DNA, to have these problems. We can succeed, we can excel.

This crisis has exposed some of the challenges of the European Union. Do you still have as much faith in the European project having gone through this recent crisis?

We are a staunch pro-European nation. I think Europe is in a transition, but I think it’s a very important transition. I would say it’s from being a peace project — which it still is — to being a model for a globalized society, a prototype for a globalized society. Europe began after the Second World War, so it basically was the dream to say: “Never again, war on this continent.” And as a matter of fact, it has succeeded in bringing in countries, making them more democratic. Greece, Spain, Portugal initially, then the Central and Eastern European countries. It still is a living peace project, creating hope in the region we’re living in, the Western Balkans, torn through wars, countries breaking apart. Europe is a peace project, but at the same time, it also is a project of what we should be able to see in a globalizing world. (See pictures of the global financial crisis.)

What does that mean? It means we pool our sovereignty. We, each one of these 27 countries, have given up some of our sovereignty to a higher body, the European Union. And said, we’ll be more effective if we work together. We’re different countries. We speak different languages. We have different backgrounds. We have different traditions. We’ve even been at war with each other at times, but we share a common pool of values: democracy, human rights, belief in the peaceful resolution of conflict, social cohesion and now, of course, the idea of a green economy. If we share these values, we can work together. And I think that means also regulating things: markets, our deficits, our economies.

Has this current crisis just been a bump in the development of Europe? Some more cynical analysts have said, this shows the European project is flawed and the euro is doomed.

It could have become a crisis — which would have, I wouldn’t say Europe would have imploded, but it could have created sort of an unraveling effect. I think what Europe has been able to do over the years is as it’s hit crises, it’s been able to creatively become stronger, to use the crisis as an opportunity and that’s what I’ve said also in the European Union. We want to use this as an opportunity to change Greece, but let’s also use it as an opportunity in Europe, to see what’s wrong in our rules and regulations in the eurozone. Do we need greater economic coordination and governance? In fact, the decision we made two days ago was not only about Greece, it was about Europe. It was about setting up a mechanism and even setting up a task force which may even bring in new rules, new ideas, new changes in the law, new changes in the treaty of how we govern our economy, and how we govern the European Union. That I think is the beauty of Europe, that even though it’s very complicated at times, lots of countries, lots of actors, it can also be very creative in dealing with things and move forward. (See pictures of immigration in Europe.)

Is the worst over for Greece?

I think the worst is over for the crisis that we’ve had, the sort of peak of the crisis. But there’s a lot of work to be done, difficult work. The pain is still there because the cuts, the wage cuts, the economic measures are biting and people will all feel this in the next few years. But if we do what is necessary, we’ll come out of this stronger and much more viable. And that’s what my hope is — and my belief is — that we can do this. Sometimes crises are catalysts for change. I do believe in a few years, we’ll be proud to say that we went through this very difficult time, and we’ve come out a Greece that is a different type of Greece — a new model of development, a green Greece, with green energy and tourism and so on, but also with greater capacity, more competitive, more transparent.