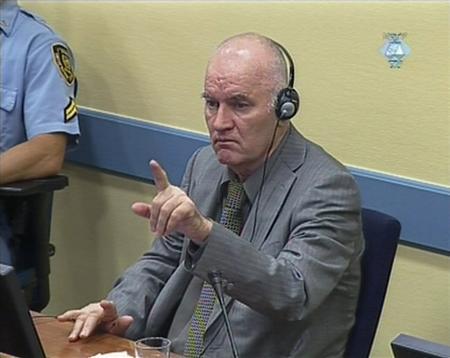

Former Bosnian Serb army commander Ratko Mladic faced the U.N. war crimes tribunal on Friday as a defiant general who never lost a battle, denying the charges against him as “obnoxious” and “monstrous.”

Formally charged by a U.N. tribunal which has waited 16 years to see him in the dock, he began with a wary appeal from a “very sick man” but ended with a defiant flourish of his old bravado, predicting he would be acquitted.

“The whole world knows who I am. I am General Ratko Mladic,” he said at the end of his first appearance, a tense 100 minutes.

“I defended my people, my country … now I am defending myself,” he told the court and rapt public gallery. “I just have to say that I want to live to see myself a free man.”

Sitting in the same chair as political chiefs Slobodan Milosevic and Radovan Karadzic, co-accused in a conspiracy to carve a Great Serbia from the wreckage of multi-ethnic Yugoslavia, Mladic began by greeting the court with a salute.

He said he was in poor health and needed more time to study the indictments against him. But by the end of the session, the general in this lifetime soldier had reasserted itself.

He told Judge Alphons Orie indignantly he did not want to hear “a single letter or word of that indictment” read out.

As expected, Mladic declined to enter a plea, and Orie set his next hearing for July 4.

“NO REMORSE”

Mladic shook his head in denial as Orie, reading a summary, described the slaughter of 8,000 Muslim men and boys at Srebrenica in July 1995, of which his second-in-command, Radislav Krstic, was convicted of in April 2004.

“He showed no remorse, he mocked the court,” said Ramiza Gurdic whose two sons and husband were killed by Mladic forces.

“It took him only three days to kill thousands of our loved ones and now he says he needs two months to read the indictment,” she said, watching Mladic on Bosnia television.

Once an intimidating figure on the battlefield, Mladic now looks his 69 years. His mouth drooped slightly at one corner and his speech sounded slurred, the possible result of a stroke.

After making the hand signal for a “timeout” to his lawyer Aleksandar Aleksic, he obtained a 10-minute private session with microphones turned off, to discuss his health problems.

Afterwards he told the court he had been treated with “fairness and dignity” since his arrest, but had one request.

“I don’t want to be helped to walk as if I were some blind cripple. If I want help, I’ll ask for it,” he said.

Medical care of defendants is a primary issue for the tribunal, after the death in custody of Milosevic in 2006, in the fourth year of his trial. Karadzic was arrested in 2008 and has been on trial since October 2009.

Mladic is also charged with crimes against humanity for the 43-month siege of Sarajevo from 1992 to 1995 in which 12,000

were killed by Bosnian Serb forces in a sustained campaign of “sniping and shelling to kill, maim, wound and terrorize.”

Dressed in a gray striped suit with a gray shirt and sober black checked tie, he frequently wiped his cheeks and mouth, stroked his chin and placed his hand on his forehead.

He listened intently to Orie, nodding or shaking a finger.

MOTHERS OF SREBRENICA

Arrested in a Serbian village, Mladic was extradited by Serbia on Tuesday to become the tribunal’s biggest case.

He had been branded “the butcher of the Balkans” in the late 1990s for his ruthless campaign to seize and “ethnically cleanse” territory for Serbs following the break-up of the Serb-dominated Yugoslav federation of six republics.

Serb nationalists believe Mladic is a hero soldier who simply defended the nation, doing no worse than Croat or Bosnian Muslim army commanders as the federation was torn apart in five years of war that claimed some 130,000 lives.

Ending years of anxious waiting to see him to brought to justice, relatives of the dead watched Mladic in court.

“I came here today to see if his eyes are still bloody,” said Munira Subasic, whose 18-year-old son and husband were both killed by Serb forces in Srebrenica.

“In 1995 I begged him to let my son go. He listened to me and promised to let him go. I trusted him at that moment. Sixteen years later, I am still searching for my son’s bones.”

The International Tribunal for former Yugoslavia, set up in 1993, expects to wind up its work by 2014. It has issued 161 indictments and has now accounted for all but one fugitive.

Serbs say the fact that two-thirds of them were Serbian is proof of the court’s bias. Hague prosecutors say it is a reflection of which side carried out the biggest war crimes.

For most of his years at large, Mladic managed to live discreetly and safely in Belgrade, relying on loyal supporters.

But as pressure mounted on Serbia to arrest him or watch its bid for European Union membership wither, his network of support dwindled, and at the end he was captured alone.