Elsewhere in Syria on Sunday, residents reported heavy gunfire in Homs, Syria’s third-largest city, and in Lattakia on the Mediterranean coast.

Amid rising defections from the army’s lower ranks, the core of people around Mr. Assad—who command army divisions and control the multilayered security apparatus—has further tightened, analysts say. Mr. Assad’s younger brother, Maher, is leading the crackdown in Jisr al-Shoghour, according to residents and activists, after deploying his army unit into other protest hotspots.

Maher Assad is the closest family member in President Assad’s inner circle, but the regime’s core includes allies that span political, economic and military circles. Key personalities include Mr. Assad’s brother-in-law Assef Shawkat, who serves as the army’s deputy chief-of-staff, Rami Makhlouf, a business tycoon and the president’s cousin, and Ali Mamlouk, the head of security.

Protesters in Idlib, the governorate in which Jisr al-Shoghour sits, have said they heard orders cited from “Abu Wael,” or Mohammed Nasif Kheirbek, deputy vice president for security affairs.

“In final decisions the family is key and it would seem inconceivable that Bashar could throw key regime members under the bus at this point,” said Andrew Tabler, a Syria expert and fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Maher Assad is characterized as a brutal and unstable character who spent his life in the military. He was one of the first targets of U.S. sanctions in this uprising which referred to the role of the army unit he commands, the Fourth Division, in the siege of the southern protest hub of Deraa.

Analysts say he is being advised by Mr. Shawkat, who was replaced as head of military intelligence last year, while security forces take a lead in commanding other army troops.

“The security forces are commanding the army unless it is the Fourth Division,” said a well-connected businessman in Homs. Mr. Mamlouk is former deputy of the Air Force Intelligence, a unit of Syria’s intelligence apparatus that activists identify as the most brutal to activists in detention.

As essential to the Assads’ ability to consolidate control, as they face the biggest challenge of their rule, is tycoon Mr. Makhlouf. Under U.S. sanctions since 2008 for alleged corruption, he is believed to have recently bought shares and Syrian pounds to prop up the stock market and currency. But as protests move past their third month, activists say the failing economy will tip over Syria’s large merchant families—key supporters of the regime—to the protesters’ side.

Army defections remain key to a potential showdown between the Assad core and the Sunni community, which dominates the rank-and-file of the army, analysts say. Every day this week, testimonies by defected army conscripts have emerged. A 21-year-old conscript who fled to Jisr al-Shoghour from Damascus earlier this week said troops live in near isolation, with no televisions or telephones, and have no information on the protests in Syria’s streets until they are deployed.

“They tell us we’re going to fight armed criminals, and we get to the streets and see kids, and elderly men, and just normal people with no weapons,” he said.

The Washington Institute’s Mr. Tabler said “The weak spot here are the rank-and-file and mid-officer corps breaking away,” adding that this was likely the scenario developing in Jisr al-Shoghour.

“Minority regimes like the Assads by their nature are galvanized against the kinds of splits like those in Egypt and Tunisia,” Mr. Tabler said. “However, even galvanized steel has a breaking point.”

Syria’s military took control of a northwestern town after surrounding it for days, as President Bashar al-Assad’s regime appeared to close ranks in the face of growing international condemnation, alienating a key ally and retreating into isolation.

The 45-year old Mr. Assad—once widely revered by Syrians as young, dynamic, and pragmatic—has sunk out of view for almost two months, as protests continue to roil and a brutal crackdown has killed over 1,400 civilians. Mr. Assad was last seen on state television addressing his new cabinet on April 16, only his second public appearance in Syria’s three-month-old uprising.

On Monday, the Syrian government imposed an international travel ban on a cousin of Mr. Assad, the Associated Press reported. The report said the move appeared to be an attempt by Mr. Assad to show that he is serious about investigating the bloodshed.

State-run SANA news agency reportedly said the ban was imposed on Brig. Gen. Atef Najib, who ran the security department in the southern province of Daraa. The uprising erupted there in mid-March after the arrest of 15 teenagers who scrawled antigovernment graffiti.

Judge Mohammed Deeb al-Muqatran of the Special Judicial Committee said the travel ban is precautionary in order for Gen. Najib to be available for questioning, the report said.

This week, Mr. Assad retrenched from diplomatic communication. The president’s office stopped taking calls from United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, after several telephone conversations in which the secretary-general urged restraint from Syria’s strongman, a spokesperson for Mr. Ban said on Friday.

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has built a strong personal relationship with Mr. Assad, on Friday accused Syria’s regime of cruelty and said several telephone calls with the president indicated the regime was “taking it all very lightly.” Mr. Assad appeared to have lost a longtime ally in Ankara’s toughened stance over the weekend.

A regime crackdown on restless cities has seen a military operation focused in the northwestern town of Jisr al-Shoughour, where the government vowed to root out armed gangs it said killed 120 police and security-force members a week ago.

On Sunday morning, residents of Jisr al-Shoghour said about 160 tanks moved into the town after shelling it from the outskirts over the weekend. The tanks shelled homes and one attack helicopter sprayed machine-gun fire between 7 a.m. and 9 p.m., a resident said. Syria’s state news agency said two “gunmen” and one soldier were killed in clashes, after which the army took complete control of the town. The state agency also reported the discovery of a “mass grave” in the town, that it said contained bodies of security-force personnel killed by the armed groups. The deployment of attack helicopters on Jisr al-Shoghour and the burning of acres of fields and hilltops in the area, as reported by residents of several towns, have represented an escalation in the attacks.

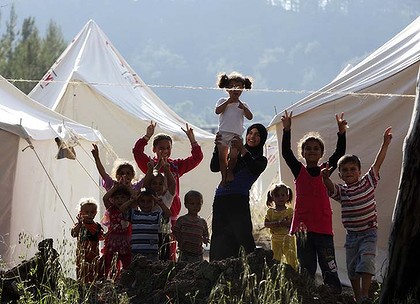

Across the border with Turkey, where thousands of refugees are being hosted in camps, a 27-year man who identified himself as Ali crossed over to get aid supplies and said “dissidents from the army blew up two bridges in the city.” Jamil Saeb, a resident of Jisr al-Shoghour and activist, said military tanks couldn’t move into the town on Saturday due to “some defectors who were trying to resist.”

Elsewhere in Syria on Sunday, residents reported heavy gunfire in Homs, Syria’s third-largest city, and in Lattakia on the Mediterranean coast.

Amid rising defections from the army’s lower ranks, the core of people around Mr. Assad—who command army divisions and control the multilayered security apparatus—has further tightened, analysts say. Mr. Assad’s younger brother, Maher, is leading the crackdown in Jisr al-Shoghour, according to residents and activists, after deploying his army unit into other protest hotspots.

Maher Assad is the closest family member in President Assad’s inner circle, but the regime’s core includes allies that span political, economic and military circles. Key personalities include Mr. Assad’s brother-in-law Assef Shawkat, who serves as the army’s deputy chief-of-staff, Rami Makhlouf, a business tycoon and the president’s cousin, and Ali Mamlouk, the head of security.

Protesters in Idlib, the governorate in which Jisr al-Shoghour sits, have said they heard orders cited from “Abu Wael,” or Mohammed Nasif Kheirbek, deputy vice president for security affairs.

“In final decisions the family is key and it would seem inconceivable that Bashar could throw key regime members under the bus at this point,” said Andrew Tabler, a Syria expert and fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Maher Assad is characterized as a brutal and unstable character who spent his life in the military. He was one of the first targets of U.S. sanctions in this uprising which referred to the role of the army unit he commands, the Fourth Division, in the siege of the southern protest hub of Deraa.

Analysts say he is being advised by Mr. Shawkat, who was replaced as head of military intelligence last year, while security forces take a lead in commanding other army troops.

“The security forces are commanding the army unless it is the Fourth Division,” said a well-connected businessman in Homs. Mr. Mamlouk is former deputy of the Air Force Intelligence, a unit of Syria’s intelligence apparatus that activists identify as the most brutal to activists in detention.

As essential to the Assads’ ability to consolidate control, as they face the biggest challenge of their rule, is tycoon Mr. Makhlouf. Under U.S. sanctions since 2008 for alleged corruption, he is believed to have recently bought shares and Syrian pounds to prop up the stock market and currency. But as protests move past their third month, activists say the failing economy will tip over Syria’s large merchant families—key supporters of the regime—to the protesters’ side.

Army defections remain key to a potential showdown between the Assad core and the Sunni community, which dominates the rank-and-file of the army, analysts say. Every day this week, testimonies by defected army conscripts have emerged. A 21-year-old conscript who fled to Jisr al-Shoghour from Damascus earlier this week said troops live in near isolation, with no televisions or telephones, and have no information on the protests in Syria’s streets until they are deployed.

“They tell us we’re going to fight armed criminals, and we get to the streets and see kids, and elderly men, and just normal people with no weapons,” he said.

The Washington Institute’s Mr. Tabler said “The weak spot here are the rank-and-file and mid-officer corps breaking away,” adding that this was likely the scenario developing in Jisr al-Shoghour.

“Minority regimes like the Assads by their nature are galvanized against the kinds of splits like those in Egypt and Tunisia,” Mr. Tabler said. “However, even galvanized steel has a breaking point.”