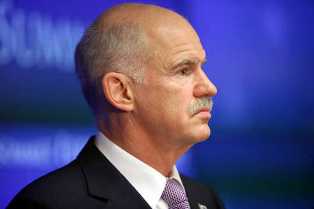

* Third-generation scion of political dynasty

* A Greek of the diaspora

* “Nice guy”, but unpredictable

By Deepa Babington, Dina Kyriakidou and David Lawder, Reuters

ATHENS, Nov 8 (Reuters) – As EU and IMF inspectors held talks in February on Greece’s failure to meet targets on reforms, Prime Minister George Papandreou summoned his cabinet to an urgent meeting.

The meeting was not on the deepening financial mess or on lenders’ demand the country pony up its family silver in return for bailout money. Instead, it was on Papandreou’s pet project — eco-friendly development.

While the inspectors debated whether Athens had done enough to merit another infusion of funds, Papandreou’s entire cabinet heard a two-hour presentation on environmentally friendly housing by architect Alexandros Tombazis and a speech by former German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer on “green growth”.

It was not the first time — or the last — that Papandreou would appear to be cut off from reality as he led a nation stumbling through its worst crisis since World War Two.

A third-generation scion of Greece’s leading political dynasty, Papandreou is almost universally described by those who know him as a “nice guy” — affable and polished, a diplomat who seeks consensus and offers a cosmopolitan perspective in the provincial world of Greek politics.

But critics and his own behaviour during the Greek crisis also paint a picture of a man who nurtures a progressive vision but lacks political savvy; an unpredictable character who can flounder when the going gets tough.

“He’s a great guy but you don’t want to be governed by him,” said Yannis Varoufakis, who advised Papandreou and worked as one of his speechwriters on economic policy issues from 2003-2006.

Initially drawn to the socialist leader’s open-minded views, Varoufakis says he left disillusioned by Papandreou’s chaotic and unpredictable management style.

The former adviser recalls that when he and other aides beavered away to formulate party education policy in 2006, Papandreou “dumbfounded” his team by walking into parliament and announcing a 10-point university plan no-one had heard of, let alone been consulted on.

Such unpredictability proved to be Papandreou’s Achilles heel. Days after euro zone leaders thrashed out a financial lifeline for Greece, Papandreou undid it all last week by calling for a popular vote on the plan. Hardly anyone — not even his finance minister — saw it coming.

In one fell swoop, Papandreou managed to roil markets, reopen the euro zone debt crisis, put his country on the path to default and out of the euro zone, and ultimately, do himself out of a job. The 59-year-old has announced he will step down to pave the way for a new coalition government without him.

“When he would feel overwhelmed he would take spontaneous decisions, more often than not of doubtful rationality,” said Varoufakis. “This is probably the last of those decisions.”

“SHOW SOME RESPECT!”

In many ways, the mild-mannered Papandreou has been an anomaly in the high-handed, macho world of Greek politics.

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, and educated in Canada, Sweden and the United States, Papandreou’s linguistic repertoire extends as far as Swedish.

Yet he can mangle his native language, at one point eliciting chortles from the opposition benches in parliament when he wrongly used a Greek expression, referring to “soft fingernails” to describe the EU’s soft stance on the previous government when the phrase actually means “childhood”.

“I am proud of being a Greek of the diaspora,” he shot back indignantly then, in 2010. “That’s enough! Show some respect, show some respect! I am a Greek of the diaspora and this was not my decision but because my father was exiled twice.”

Papandreou often practised his speeches before a mirror to avoid making grammatical errors, a government source told Reuters.

He prefers bicycling and canoeing between islands over sports seen by Greeks as more appropriately macho, like soccer.

“Green growth” is mentioned in virtually every address, including his Friday swansong speech before a confidence vote.

“Most of PASOK doesn’t even get George,” said an official at his socialist PASOK party.

The party his father founded after the fall of the military dictatorship adored the late Andreas Papandreou and for a while, in the nepotistic world of Greek politics, that seemed enough.

“George became prime minister by default, because of the great deal of affection the party had for his dad — they gave him minimal resistance and maximum tolerance,” Varoufakis said.

The eldest of four children, George was born to an American mother, Margaret Chant, and Harvard-trained economist Andreas, who was remembered, among other things, for his flamboyant love life and an unforgiving style that included firing ministers without warning.

Andreas himself had switched from academia to politics when his father Georgios Papandreou became prime minister in 1963.

Young George’s first brush with politics came in 1967, at age 14, when Greece’s new military leaders sent soldiers to the Papandreou home in Athens to arrest his father.

“Here was a kid whose first real taste of Greek politics was a soldier pushing the barrel of an American-made rifle into his temple, yelling upstairs that if Andreas didn’t come down, they were going to kill his son,” said Richard Parker, a Harvard lecturer who has known the Papandreou family since the 1970s.

“That was a huge shock to him.”

Fearing for George’s safety, his mother sent him off to her hometown of Elmhurst, Illinois, to stay with her sister, Evelyn Nottelmann. There George settled into a normal suburban Chicago life, going to the same public high school his mother attended.

Nottelmann, who said George has called her his “second mom”, recalls him doing well at the school and being popular.

She described him as an attentive and bright child who often played guitar with her son Greg, who was about the same age.

“Having him in our house just felt like we had another son,” she said. “He and his cousins had a lot of laughs.”

“TYPICAL AMERICAN STUDENT”

The young Papandreou’s socialist leanings came into full bloom at Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he forged friendships with fellow Greek students, including his now archrival and conservative opposition leader Antonis Samaras.

In an era marked by Vietnam War protests, Watergate and political upheaval in the United States, the two young men spent many discussions decrying the military junta ruling Greece, sometimes over pizza in their dorm rooms.

Their divergent views on Greece’s future were yet to be fully established.

Papandreou was a true socialist who preferred the student protest attire of the Vietnam War era — plaid flannel shirts, jeans and long hair, said Philip Tsiaras, a former classmate at Amherst. He strummed his guitar and sang protest songs.

Samaras was a conservative, “centrist” thinker who favored blue blazers — “probably Pierre Cardin” — with gold buttons, gray slacks and black loafers, Tsiaras said.

Despite being a descendant of the Greek political elite, George didn’t pretend to know a lot about European politics, said Amherst political science professor Ronald Tiersky, who taught him the subject.

But as a “typical American student” who was somewhat shy, he was eager to learn, Tiersky said.

“George was a young man who exuded integrity,” Tiersky said. “You really got the sense that this was someone who was willing to tell the truth and take responsibility.”

Papandreou would return to Greece in his late 20s and became active in his father’s party. In 1981, the same year his father became prime minister, he was elected to parliament — setting in motion a slow rise to the top of Greek politics.

Along the way, Papandreou held various ministerial portfolios including foreign affairs — where his discreet diplomacy skills came to the fore — and helped coordinate Athens’ bid for the 2004 Olympic Games.

He took control of the party in 2004, leading it through two election defeats. But his first serious challenge came in 2007, when he saw off a threat from Evangelos Venizelos — his current finance minister — for the party leadership.

A RELUCTANT LEADER

Papandreou initially seemed determined to usher in change to Greek politics.

He has said he decided to ignore the well-meaning advice he got when he was first elected a member of parliament — that he had to “bang the table” to show he was in charge.

“Even though we came in on a wave of popular support for change, people advised me that once in government, you had to take on the trappings of government and the traditional style of leadership,” he told the openDemocracy.net website in 2004.

“People would say you look weak if you’re not cursing the opposition and driving around in a big black car while always wearing a tie. Above all, to be ‘strong’ you’re always supposed to be giving orders.”

That was not his style. Tsiaras remembers him as a “down-to-earth guy” unafraid to get his hands dirty and gave an example from a dinner visit in New York when he was on a trip to the United Nations as foreign minister several years ago.

“The ice-maker was broken, so he got down on his hands and knees and fixed it,” said Tsiaras.

He also picked young talent for top party positions and tried to purge an old guard associated with decades of socialist graft. But his choices were often seen as erratic, especially when he became prime minister in 2009.

When Greece catapulted itself into the global spotlight as an economic basket case by the admission it had cooked its deficit figures, the ensuing crisis proved beyond his motley crew of advisers and aides, an odd mix of old PASOK devotees and foreign experts with scant knowledge of Greek reality.

Papandreou emerged as the only one in his government who could stand in front of international cameras and make a case for his country.

Over the years, his inner circle has been whittled down to advisers who do not disagree with him, says Varoufakis.

“DENMARK OF THE SOUTH”

In his two years at the helm, Papandreou was unable to effect any real change to endemic corruption in Greece or improvement in the lives of the average Greek.

With his political career in tatters, Papandreou has appeared isolated in recent months, with the anger directed at him by ordinary Greeks taking an emotional toll.

“I don’t think that George ever really wanted to be prime minister. He was the heir apparent, but it was almost something he had to do — it was something that was expected of him, a dynastic kind of thing,” said Tsiaras.

“The irony is that George has been forced to be a conservative, dictatorial leader. How else do you get the unions to stop doing what they do?”

Those close to him say he sees himself as a victim of Greece’s corrupt interests, a tragic hero who fought and lost the battle to turn Greece into “the Denmark of the south.”

Greek papers reported his first offer to resign in June came soon after he was heckled while walking on the street.

Nikos Sideris, a Greek psychoanalyst and author, said Papandreou became “trapped in a narcissistic fantasy” of seeing himself as a prince with the right to lead the country — a fantasy that came undone when he was booed by average Greeks.

“His narcissism was threatened,” said Sideris.

At what may have been his final speech in parliament, Papandreou last week said he was leading an administration that was being pelted with stones while “bearing a cross”.

“George is a real person in an unreal situation,” Tsiaras said. “I think if he had his druthers, he’d probably like to take his guitar and go somewhere … remote.”