By Eric Spitznagel, Business Week

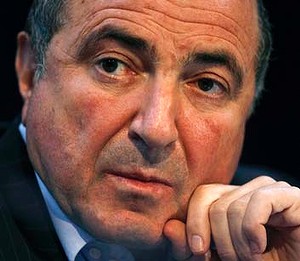

Who was Boris Berezovsky again?

A self-made billionaire—at the height of his wealth in 1997, Berezovsky’s estimated worth was $3 billion, according to Forbes—a former academic who, after the privatization of the Soviet Union’s state-run economy, built his fortune with investments in oil, cars, airplanes, aluminum, and TV stations. Berezovsky played an integral part in Vladimir Putin’s rise to power in 2000. Once elected, Putin lashed out against oligarchs, charging many with tax evasion. In 2000, Berezovsky fled to England, where he lived until his death.

What happened?

On March 23 he was discovered in a bathroom at his home in Ascot, Berkshire, by his bodyguard and pronounced dead by paramedics shortly after. The Thames Valley Police reported that Berezovsky was found with “a ligature around his neck and a piece of similar material on the shower rail above him,” and the death was “consistent with hanging.” But there was no suicide note, and, according to the police, the involvement of a second party “cannot be completely eliminated, as tests remain outstanding.” Nikolay Glushkov, a longtime friend of Berezovsky and a fellow Russian exile, suspects foul play. “The idea that he would have taken his own life is bulls- – -,” Glushkov told the Guardian. “Berezovsky had a lot of powerful enemies,” says Mark Galeotti, a professor at the Center for Global Affairs at New York University. One name that’s mentioned repeatedly is Putin’s.

Why would Putin want him dead?

“Putin understands that oligarchs are truly kingmakers,” Galeotti says. “And a kingmaker could easily become a king-breaker. So he set out to either force them to submit to the Kremlin or destroy them.” Oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky was arrested in 2003 on charges of fraud and sent to a Siberian prison camp, where he remains to this day. Berezovsky taunted the Kremlin from afar, speaking publicly about what he called Putin’s “major crimes in Russia.” In 2007, Scotland Yard allegedly advised Berezovsky to leave England because of a possible assassination attempt. (Putin is not the first to allegedly target Berezovsky: In 1994 he was nearly killed in a car bomb in Moscow. His bodyguard lost an eye and his chauffeur was decapitated.)

Berezovsky had money problems at the end. How’d he lose all that cash?

Berezovsky’s second divorce in 2011 cost him roughly $154 million. In August he lost a legal battle against his former business partner, Roman Abramovich, whom he accused of blackmail and breach of contract in coercing him to sell his stake of their oil company, Sibneftegeofizika (SNGF). The judge awarded Abramovich $5.6 billion and called Berezovsky “dishonest.” Berezovsky gave a final interview with Forbes the day before his death, saying, “I’m 67 years old. And I don’t know what I should do from now on.”

Has this kind of thing happened to other oligarchs?

In December 2007, Georgian billionaire Arkady “Badri” Patarkatsishvili—who, like Berezovsky, initially supported Putin and went into exile after Putin’s election—told the Sunday Times there was an assassination plot against him orchestrated by the Kremlin. He died a little more than a month later at his Surrey mansion of what pathologists concluded was a heart attack. In November 2012, Russian whistle-blower Alexander Perepilichnyy, who had been helping Swiss authorities uncover a money-laundering scheme by Russian officials, dropped dead while jogging outside his Surrey home, also of an apparent heart attack.

Will we ever know the truth about any of these guys?

Pathologists are working on Berezovsky’s toxicology and histology tests, which could take weeks. “If the authorities are looking hard,” Galeotti says, “they’ll find out if there are traces of poison.” Both journalists and conspiracy theorists on the Web, have pointed out that sodium fluoroacetate, a chemical used in pesticides, can cause heart failure and is difficult to identify. Peter Earnest, the executive director at the International Spy Museum, in Washington and a former CIA operations officer, says conspiracies thrive because sometimes they turn out to be true. “These Russian oligarchs dying in suspicious ways may sound like the plot of spy novels, but you never know,” he says.