By Jenny Paris, The Wall Street Journal

A little before midnight, signals of the Greek Radio and Television, known as ERT, went silent after 47 years of operation.

Defying the government’s orders, most of the network’s 2,700 fired journalists and technicians remained at the broadcasters’ headquarters and continued streaming programming online through the night while hundreds of protesters had camped outside.

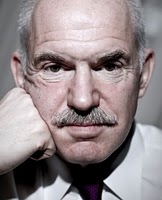

The government’s decision is its boldest move yet after resisting for years to comply with demands by international lenders to slash its bloated public sector workforce, and will no doubt be seen as a defining moment in the country’s economic struggles.

But it’s also a big political gamble that could threaten the unity of the ruling coalition, which has brought together the main conservative party with the socialists and a small leftist party in an unlike and fragile partnership.

Both junior partners, the Pasok and Dimar parties, opposed the move and have said they won’t back legislation for the creation of a new broadcaster in parliament. Whether they’ll grudgingly allow the government to proceed with its plans or will rebel against the decision, risking an early election, will depend on the public’s reaction in coming days.

In a country where blank television screens are associated with disturbing memories of the 1967-1974 military dictatorship, the political risk for prime minister Antonis Samaras may go beyond a showdown with the laid-off journalists. The country’s main labor unions have called a general strike for Thursday to protest the decision, while some commentators have likened the workers’ protest to the occupation of Greece’s Polytechnic School by students in 1973 that eventually led to the ouster of the military junta.

In a harshly worded statement, the radical leftist opposition Syriza party described the decision as a “coup that is directed against not only the ERT workers but the entire Greek people.” For Syriza, which had seen its lead trimmed in recent opinion polls, this could be an opportunity to regain its popularity further threatening the government’s survival.

Yet, for some in the public the move may be seen as long overdue after years of mismanagement and political patronage had created what many saw as a wasteful government public relations machine. With their incomes slashed and slapped with steep taxes, Greeks still had to continue to finance ERT through their electricity bills. And the company’s oversized staff was the result of jobs handed out by each new government to its supporters, so they could continue to report favorably on it.

Known mainly for its lengthy news broadcasts and documentaries, ERT is also unlikely to be missed by the wider public which in recent years had been increasingly tuning in to the popular soap operas and more sensationalist news reports offered by the private TV channels. ERT’s three channels had a combined audience of about half of that of an average commercial station.

Ironically, its online programming is now attracting more viewership than ever before, while support messages are the top trend on Facebook and Twitter among topics in Greece Wednesday.

“While the public perception of ERT has hardly been uniformly positive, the sudden appearance of blank screens across the country will enter the public consciousness in a way which other measures may not have done,” Alex While, and analyst at J.P. Morgan Chase, said in a note. “Further strikes throughout this week are likely, and it is possible that the Government could be forced to back down following party meetings over the coming 48 hours. The next few days will provide an important indication of whether Greece is slowly working itself loose of past political constraints, or will be dragged back.”