By SUZANNE DALEY, New York Times

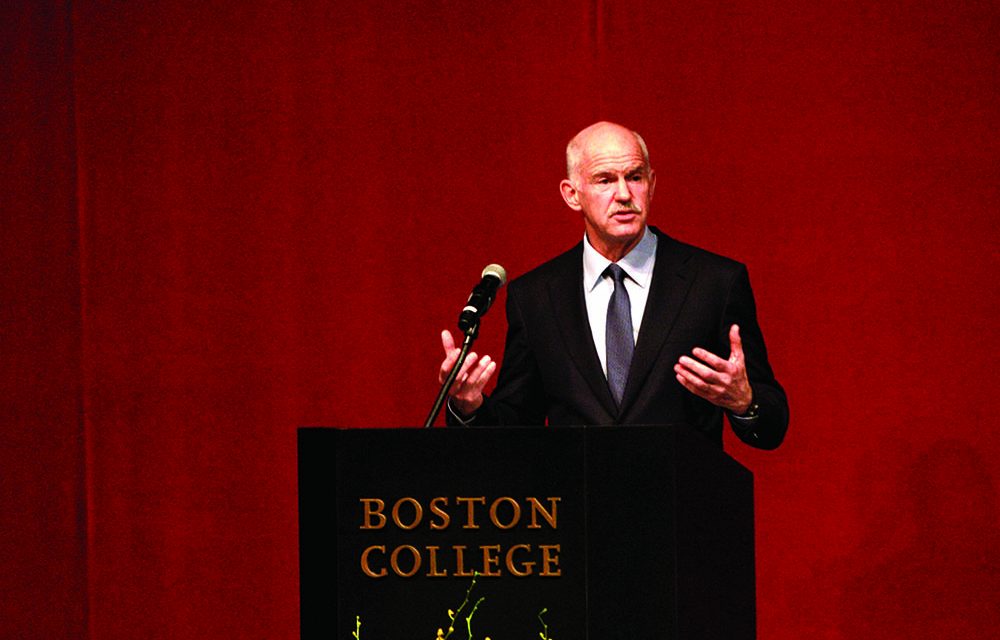

ATHENS — Former Prime Minister George A. Papandreou, who was forced to step aside in 2011, has burst back onto the political scene here with a bid to wrest control of his Socialist party from his successor.

Mr. Papandreou, who made his move in an open letter last week calling for an emergency party congress to pick a new leader, has thrown even more uncertainty into Greece’s volatile political landscape.

The party, Pasok, which has been part of a governing coalition for the past two years, has seen a huge decline in its popularity. But analysts believe that the return of Mr. Papandreou could bolster the party’s fortunes, reordering the fragmented political landscape, particularly if elections are held early next year as seems increasingly likely. Mr. Papandreou would be likely to draw votes away from Syriza, Greece’s new leftwing party, which at the moment is far ahead in polls.

Under some scenarios, political analysts say such a development could make Pasok a crucial player in determining who leads the country after the next elections, which could be held as early as March. It is far from clear, however, that Mr. Papandreou would succeed in ousting Evangelos Venizelos, who took over the party after Mr. Papandreou infuriated European Union leaders with his idea for a referendum on Greece’s bailout by international creditors.

Mr. Papandreou hoped a chance to vote on the issue would end the protests that had become a part of daily life in Greece. But European Union leaders believed that it would inject more uncertainty into financial markets and that it could collapse the euro. Mr. Papandreou’s call for an emergency meeting to choose a new leader even took members of his own party by surprise. Since then, a few central figures in Pasok have supported the former prime minister’s call. But Mr. Venizelos has dismissed the notion outright.

Analysts say it is hard to predict what will happen. “It is difficult to say who will win,” said Nick Malkoutzis, the editor of the political analysis website MacroPolis. “It is still very fresh. No one suspected that Papandreou would try and put himself back in

center stage.” Mr. Papandreou has not yet said he will try to lead the party himself, though people close to him said they believed he would. Regardless, the standoff within the party has been frontpage news for days, with some speculating that the party may simply split. Current polls suggest that Pasok would receive only 5 percent of the vote with Mr. Venizelos, who is one of the least popular politicians in Greece, as its leader. Mr. Venizelos has been considering partnerships with smaller political groups and a possible name change to the party in a bid to garner more support.

In his letter, Mr. Papandreou criticized the leadership of Pasok for focusing on such strategies instead of the needs of the people. In an interview, Mr. Papandreou said he had called for the party conference because “things are off track.” As a longtime party member, he said, he felt it was time to step up and take “responsibility.”

“After five years of hard sacrifices by the Greek people, you can’t do petty politics,” he said. Mr. Papandreou, whose father and grandfather were prime ministers, said he wanted to see a bottomup rejuvenation of his party and did not rule out the possibility that Pasok, which has been part of the ruling coalition with the centerright New Democracy, could team up with the leftwing Syriza in the future.

Mr. Venizelos, who is also deputy prime minister and the foreign minister, reacted angrily to Mr. Papandreou’s letter, saying in a formal statement that the party had already chosen a leader. Mr. Venizelos’s aides have also accused Mr. Papandreou of adding instability to the government at a time when it is trying to negotiate yet another deal with its creditors. Asked for comment on the move, one aide to Mr. Venizelos said he had “no time for such nonsense.”

New elections would not ordinarily be scheduled until 2016. But Parliament must choose a new president, a largely ceremonial job, in February with 180 out of 300 votes. If that cannot be achieved, which looks very likely at the moment, the current unity government, led by Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, must be dissolved and new elections scheduled. Recent polls show that Syriza, led by Alexis Tsipras, would win a March election, with about 28 percent of the vote. New Democracy is appealing to barely 20 percent of all Greeks. Pasok in recent polls would have about 5 percent of the vote, a far cry from the 45 percent that Mr. Papandreou won in 2009.

No one thinks Mr. Papandreou could get anywhere close to those numbers today. But Takis Theodorikakos, the head of the polling group GPO, said that with Mr. Papandreou at the head of Pasok it might score 4 or 5 percentage points higher. “He has a core of loyal followers,” Mr. Theodorikakos said. But, he added, there are many Greeks who blame him for signing the first bailout agreement and for the austerity cuts they have endured ever since at the hands of their creditors.

Since he stepped aside after just two years in office, Mr. Papandreou has remained a member of Parliament. But until recently, he said little and spent a lot of time out of the country.

Correction: November 28, 2014

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that George A. Papandreou’s father and grandfather were former Pasok prime ministers. They were former prime ministers, but the party did not exist when his grandfather was in of ice.