Underestimating the Risk From Greece Would Be Unwise

By RICHARD BARLEY, Wall Street Journal

The eurozone is playing with Greek fire again. One suggestion is that, unlike in 2011 and 2012, the region is now strong enough to withstand a Greek exit from the euro. That is a dangerous idea.

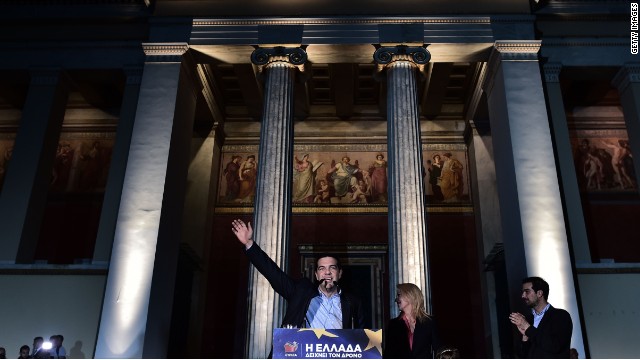

Greece’s elections, due Jan. 25, are being painted as a renewed referendum on whether the country remains in the single currency. That probably overstates the risks: the left-wing Syriza party, leading the polls, isn’t campaigning for an exit and a majority of Greek voters want to keep the euro. But a victory for Syriza, which wants Greece’s debt burden to be eased, will lead to tricky negotiations with the rest of Europe. If those negotiations become a standoff, events might yet conspire to propel Greece out of the euro.

To be sure, there is little sign of worry in financial markets over this risk, in sharp contrast to previous debates about “Grexit”. Greek bonds have collapsed, but 10-year yields for Italy and Spain are well under 2%; for Portugal they have fallen under 2.5%. Contagion is noticeable by its absence. But the decline in yields is a response to the prospect of the European Central Bank buying eurozone government bonds, an event that is much more likely than a Greek exit.

Yes, the eurozone is in a stronger position than it was three years ago. Countries like Spain, Portugal and Ireland have moved to address their problems, and firewalls like the European Stability Mechanism, the eurozone’s bailout-financing vehicle, are in place. Greece’s 2012 bond-restructuring means that exit and default aren’t a threat to the European banking system; the bulk of Greek debt is now owed to eurozone governments and the International Monetary Fund.

But a Greek exit would still pose fundamental threats to the euro in the long run. A key ECB tenet is that the euro is irreversible. ECB President Mario Draghi ’s pledge to buy eurozone government bonds if necessary under the Outright Monetary Transactions program was based on the idea that investors had irrational fears about a collapse of the euro. An exit would destroy these foundations: a precedent would be set. If one country can leave, so can others.

And while the eurozone’s institutional framework is stronger than it was, it is by no means complete. Political will has kept the single currency intact so far, but new parties that challenge the orthodoxy of euro policies are garnering support. Countries “have to be better off inside [monetary union] than they would be outside,” says Mr. Draghi. Yet Italy’s economy is barely bigger in real terms than it was in 2000. Unemployment is over 10% in nine eurozone countries.

Markets may be taking Greek risk in their stride for now—the election is still three weeks away. But to rely on that continuing would be complacent.