Despite Greece’s problems, Eurozone recovery is strengthening

By Simon Nixon, Wall Street Journal

ENLARGE

ENLARGEAfter weeks of brinkmanship between Greece and the eurozone, one might think the outlook for Europe was bleak. Since the election of a radical leftist-led government in Athens in January, a breakup of the supposedly irreversible single currency has looked more likely than ever. It took an 11th-hour deal finalized last week to avert imminent Greek bankruptcy—and already this fragile truce is under strain.

Eurozone policy makers claim that they only tolerated a degree of vagueness in a list of Greek reform commitments required as part of that deal to help Athens obscure the scale of its climb-down from its domestic audience. But Athens insists the lack of detail is evidence of “constructive ambiguity” that leaves the exact nature of what it has agreed open to continued negotiation. Thus the uncertainty over Greece’s fate is set to continue.

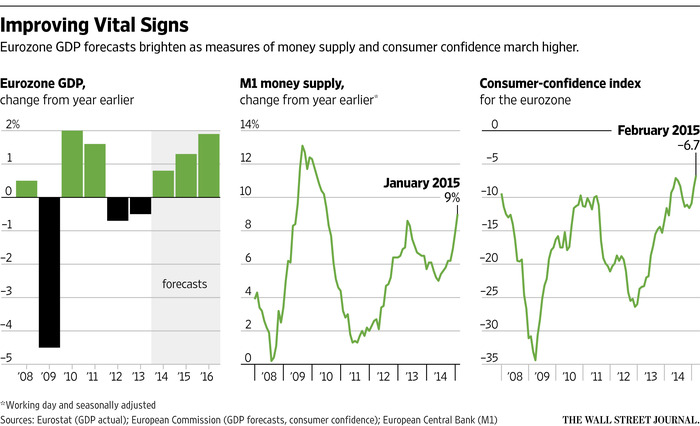

Yet focusing on Greece only tells part of the story. Equally important to the long-term fate of the currency bloc is growing evidence that the recovery is strengthening, thanks to a weaker currency, which has fallen 19% against the dollar since the start of 2014; a falling oil price, which is likely to add up to 1.5 percentage points to the level of output this year, according to Huw Pill, chief European economist atGoldman Sachs ; and the lower borrowing rates and boost to confidence from the European Central Bank’s new government-bond buying program due to start this week.

For the first time since 2007, the European Commission expects every country in the bloc to post positive growth this year. Its forecast of eurozone growth of 1.2% this year was made before the ECB announced its quantitative-easing program. Goldman Sachs last week raised its forecast for growth this year to 1.5%.

Eurozone money supply—cash and bank deposits—rose at an annualized 9% in February; the last time it rose this fast, the eurozone economy was soon growing by more than 2%, notes Holger Schmieding, chief economist of Berenberg Bank. Bank lending is growing again for the first time since 2008. Recent surveys suggest economic confidence is returning.

True, growth is likely to remain well below levels in the U.S. and U.K. and output in many countries remains below peak levels.

But the aggregate eurozone data masks important national variations. Germany is motoring again after a wobble last year: Growth in the fourth quarter was 0.7% and unemployment is down to a post-unification record low of 6.5%.

Of particular interest to Keynesian economists who have long urged Germans to spend more, Germany’s largest trade union last week agreed a new 3.7% annual wage increase that is likely to apply to its 3.5 million members nationwide, the largest rise since 2007.

Meanwhile, some of the fastest growth in the eurozone is being delivered by former crisis countries such as Spain, Portugal and Ireland. The commission forecasts growth in Spain will hit 2.2% this year but privately Spanish officials are hopeful the outcome will be between 2.5% and 3%, driven by increased consumer spending and business investment. Spanish house prices have finally stopped falling for the first time since 2008.

Even in France and Italy, the two countries that have made the least progress on reforms and whose economic weakness undermined hopes of a stronger eurozone recovery last year, the outlook is improving. French unemployment finally fell in February and survey evidence suggests a recovery in the service sector. In Italy, consumer confidence has hit a 14-year high and fear of unemployment a 10-year low. The Italian economy is finally expected to return to growth this year, perhaps as soon as this quarter.

ENLARGE

ENLARGEThese days it is a truism to point out that the biggest risks to this recovery are political. Greece has demonstrated how a tentative recovery can be quickly snuffed out by a political crisis and change of government. Since last December, activity in Greece has slowed, tax receipts have collapsed and an estimated €20 billion ($22.35 billion) of deposits have been withdrawn from the banking system, raising the prospect of a renewed credit crunch.

Populist parties similar to Greece’s Syriza are running high in the polls in a number of eurozone countries, their support reflecting unemployment that remains alarmingly high and anger at the corruption of traditional political elites. These include Spain, where a new radical leftist party, Podemos, is leading in many polls, and Ireland, where Sinn Fein is also performing strongly. Both countries face elections in the next 12 months.

But political risks can cut both ways. The combination of crisis in Greece and recovery elsewhere is changing the terms of debate.

The key lesson of the Greek crisis is that no country can be truly sovereign or economically successful without access to markets. If the government can’t fund itself, it’s unlikely the country’s banks and companies will be able to either.

The contrast between Greece and Spain, Portugal and Ireland, where capital is once again flowing, helping to create jobs, is stark. No surprise then that the governments of those countries have been the least willing to yield anything to Athens that might strengthen the hand of domestic opponents. Indeed, it is striking that Portugal’s center-right coalition last week drew level in the polls with the opposition socialists, while in Spain, a new centrist party is drawing some support from Podemos.

More importantly, the recovery has altered the balance of power in the eurozone; Athens has discovered that it has even less leverage than it thought over its creditors.

From 2010 to 2012, it was the fear of contagion to other crisis-hit countries that led the eurozone to provide two successive bailouts to Greece. This time, there has been no market pressure on the eurozone to buckle to Greek demands. As a result, the balance of risks between a Greece exit from the eurozone, with the damage this might do to the illusion of irreversibility, versus the very real risk of undermining the legal and institutional foundations that govern the monetary union looks more evenly balanced.

The fact that Greece’s brinkmanship has so far damaged no one other than ordinary Greeks may yet prove the most decisive new political reality to emerge from the current crisis.