By Mark Gilbert

With Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem saying it’s “unthinkable” that Greece will get any new aid by the time its existing rescue agreement lapses on June 30, the nation’s euro membership really is one minute to midnight.

But, with all due respect to Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s democratic right to pursue whatever course of action he believes to be in his country’s best interests, leading Greece out of the euro region and into the potential wasteland of failed statehood without an explicit mandate from the Greek public would be a monumental error of judgment.

Tsipras said on Wednesday that the government “will assume the responsibility to say ‘the big no’ to a continuation of the catastrophic policies for Greece.” But polls have consistently shown that Greeks don’t want to leave the euro. A poll for Greece’s Mega TV this week showed 56 percent would prefer a “bad” agreement that submits the country to yet more austerity; just 35 percent said they’d prefer to leave the common currency.

A rally in Athens on Thursday attracted thousands calling for the government to stay in the European monetary union. European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s European People’s Party tweeted that “we welcome the pro-EU rally yesterday in Athens clearly showing that people in Greece want to be part of the EU and the eurozone.” Ideally, mass rallies of this sort would also carry weight with Greece’s elected leaders.

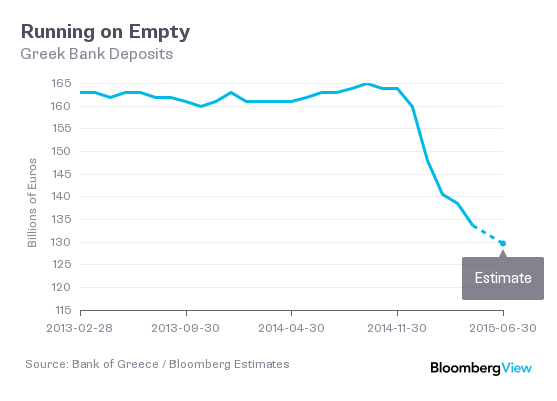

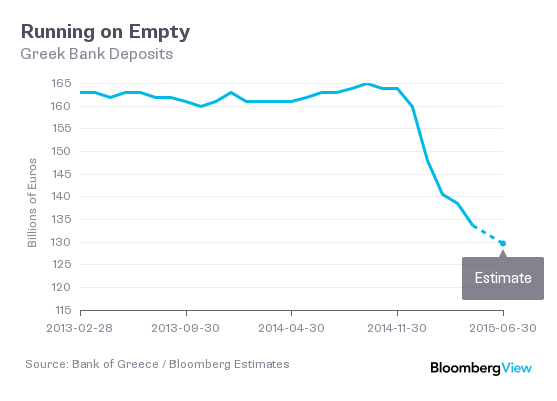

While Greeks aren’t yet storming banks, they are sucking their money out of the banking system at an accelerating rate. Withdrawals have already topped 4 billion euros ($4.5 billion) this month; 1.85 billion euros was taken out just on Wednesday and Thursday, a person familiar with the figures told Bloomberg News. And while Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis decried “pernicious ‘leaks’ to the press regarding Greece’s banking system,” it’s undeniable that insolvency looks increasingly unavoidable for the nation’s financial system. Estimates suggest there’s less than 130 billion euros left in Greek bank accounts, a drop of almost 20 percent so far this year:

The risk of capital controls that might close the country’s ATMs is prompting nervous tourists to favor cash over plastic, and stockpile banknotes in hotel safes. Asked by Dijsselbloem on Thursday whether Greek banks can remain open, European Central Bank board member Benoit Coeure said “tomorrow, yes. Monday, I don’t know,” according to Reuters. Bookmaker Paddy Power is offering odds of 4/5 on Greece leaving the euro, meaning a 1 euro bet wins 80 cents plus the return of your stake; in February, that same bet had a potential profit of 1.375 euros.

The wider question of whether the euro will be stronger (goodbye and good riddance to a turbulent member) or weaker (if one country can leave so can others) if Greece goes remains unsolved. Here’s what the currency did yesterday as traders parsed headlines about a possible deal that were swiftly followed by a German denial:

Just as it’s possible the euro might rally after a Grexit, it’s possible Greece might be better off out of the euro, with a massive devaluation of the new version of the drachma goosing the economy. But going that route should be a decision for the Greek people, not a leadership that’s squandered five months in fruitless bickering with the country’s lenders.

There’s no mechanism in place for the European Commission to kick a country out of the common currency; nor are there rules about how a voluntarily exiting member should go about its departure. But if Tsipras is the staunch democrat he claims to be, he needs to swiftly and unambiguously put the “in or out” question to his people — and then abide by their answer.