The Economist

A MONTH ago Greek membership of the euro was in peril, as Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s powerful finance minister, argued that Greece should leave the monetary union for at least five years in what he euphemistically called a “time out”.

Any such exit, which would almost certainly have turned out to be permanent, would have undermined a founding principle of the monetary union—that those joining the euro do so irrevocably. Even after euro-zone leaders meeting at a crucial summit managed to agree upon a framework for a bail-out agreement on July 13th the chances of it actually being concluded and avoiding a “Grexit” seemed slim. Mr Schäuble made clear in the following week that he still thought Greece should be temporarily expelled from the euro while Alexis Tsipras, the Greek prime minister, said he did not believe in the agreement he had just made at the summit.

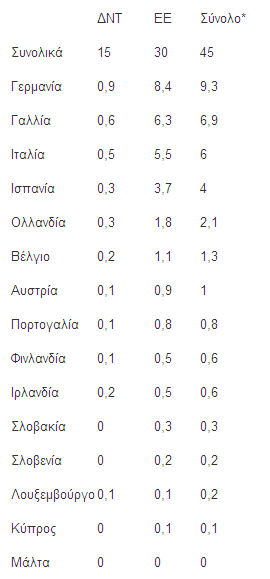

Yet, on August 14th, the Eurogroup of euro-zone finance ministers gave the green light to the bail-out, the third since May 2010, in which Greece will get up to €86 billion ($95 billion) in rescue funding over the next three years. The next hurdle is getting the consent of the German Bundestag, but this is unlikely to be a problem since the bail-out now has the support of Mr Schäuble. Even if national parliaments in smaller countries were to balk at the agreement this would not derail it because the voting procedures of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the euro zone’s rescue fund, allow decisions to be passed in an emergency with 85% of the votes, which are weighted by capital shares reflecting the size of economies. This means that whereas a large country like Germany can block such decisions smaller states cannot do so.

As a result, Greece looks set to get a disbursement of €13 billion ($14.4 billion) by August 20th, in time to redeem €3.2 billion of bonds held by the European Central Bank (ECB), which come due that day. A further €10 billion will be set aside immediately at the ESM to cater for a portion of expected bank recapitalisation needs in an economy traumatised by the events of late June and July when the banks were closed for three weeks and capital controls were introduced. Greece will get a further €3 billion in the autumn, subject to the government complying with “key milestones” in the formal agreement, the memorandum of understanding. Altogether then the first tranche of funds will amount to €26 billion. An additional amount of up to €15 billion will also be made available to bolster the banks (taking the total to €25 billion) no later than mid-November following a thorough appraisal of the banks including stress tests.

Unlike the first two bail-outs, the IMF is not involved, as yet. The fund remains scarred by its experience in the first one, in May 2010, when it sanctioned its contribution in order to prevent wider financial and economic contagion even though this meant breaking one of its cardinal rules, since it could not state with a high probability that Greek public debt was sustainable in the medium term. Now the IMF is insisting that euro-zone countries commit to significant debt relief going well beyond what has already been provided (for example by lengthening the maturities of European loans) as a condition for joining the new bail-out. This creates a dilemma for the Germans in particular. On the one hand they would like to have the IMF on board because they believe it would be a sterner taskmaster than the European Commission in monitoring Greece’s compliance with the agreement and would also contribute some of the bail-out money. On the other hand they are reluctant to offer the scale of debt relief that the IMF has in mind not least since this might spur similar demands from other rescued countries.

Even though the IMF’s role is yet to be determined the Eurogroup’s decision on August 14th marks an extraordinary turn of events, enabling Jean-Claude Juncker, the Commission’s president, to claim that Greece was now “irreversibly” part of the euro area. What has made the difference is the change of heart by Mr Tsipras, who had won power in January this year promising to end the era of reviled memorandums and bail-outs. That led to almost half a year of confrontation with international creditors, reaching a climax when he called a referendum in late June on their proposal and campaigned against it. Even though he prevailed in the referendum, with a 61% no vote, it was a Pyrrhic victory as the economy was strangled through capital controls while Germany backed by several other euro-zone countries sought to force Greece out of the euro. That forced the prime minister to junk his previous strategy and to accept the harsh terms set by creditors.

That decision on the part of Mr Tsipras has made the third bail-out agreement possible but it has split the ruling Syriza party, which has 149 seats out of a total of 300 in the Greek parliament, exposing the underlying divide between a majority of relatively pragmatic MPs in the party and a significant minority of vociferous and hard-line dissidents. On three occasions now, the Greek prime minister has had to rely upon the votes of the opposition parties to force through the harsh measures demanded by the rest of the euro area in order to pave the way for a final bail-out agreement. The dissent within Syriza has swelled. On the first crucial vote, just days after the summit, taken in the early hours of July 16th, 32 members voted against legislation and six abstained (while one was absent). In the vote of August 14th, preceding the Eurogroup summit, 32 voted against and 11 abstained, taking the total number of dissidents to 43.

The scale of the revolt is such that Mr Tsipras will probably have to call a vote of confidence in parliament. If that goes against him, it will precipitate an early election. Since the prime minister remains remarkably popular, that could reinforce his position as the leader of a more realistic party, shorn of Syriza’s hard-left wing, auguring well for the chances of Greece’s third bail-out agreement working. But this outcome cannot be taken for granted. Just as before, political risk could blight Greece’s prospects.