By Steven Kelly, University of Wisconsin. Contributor at the International Political Economy Hub blog- Huffington Post

The United States Congress recently finally approved the 2010 International Monetary Fund (IMF) quota and governance reforms. While the delay since at least 2012 in approving these reforms demonstrates the general lack of understanding of the institution’s importance and benefits among many of the world’s policymakers, the stipulations that came with this final approval make it even clearer. One of the less unreasonable stipulations was a requirement that the U.S. IMF Executive Board member join his fellow members concerned about moral hazard to push for a repeal of the “systemic exemption” enacted in 2010 which allowed the IMF to lend to Greece despite its insolvency as a means to prevent financial collapse in Europe. Looking at the financial panic that ensued after allowing Lehman Brothers to fail in the United States in 2008, welfare concerns certainly argued in favor of throwing Greece a lifeline.

Despite the importance of such fire-prevention by economic policymakers, given that Europe’s economy later “double-dipped” into recession, is today still recovering weakly, and lacks consensus amongst its policymakers to get it out of economic stagnation, it is worth considering the counterfactual in Europe’s case.

Yes, economically-speaking, the IMF lifeline to the nearly-in-default Greek government was likely a good idea towards policymakers stated goal of avoiding (additional) systemic financial collapse. However, given that the politics of Europe have prevented a robust economic recovery since then, one has to wonder if the political environment would be more recovery-friendly had the IMF let Greece collapse. The tune of the economic recovery plan in Europe since 2010 has been austerity and then, when that doesn’t work, more austerity. The eurozone (EZ) periphery countries that over-borrowed after EZ accession and ran up massive current account deficits-most notably Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Greece-have been forced to undergo drastic spending cuts and tax increases to get their financial houses in order. Meanwhile, the countries that were running surpluses have not been required to undergo countervailing stimulus measures. Thus, the recovery plan in Europe has been dubbed to have a “deflationary bias”-demand has been curbed in deficit countries via required austerity measures but is not required to increase in surplus countries. Thus, Europe’s economy has been facing a chronic problem of weak demand and weak inflation, despite a mild pickup due to the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing (QE) program.

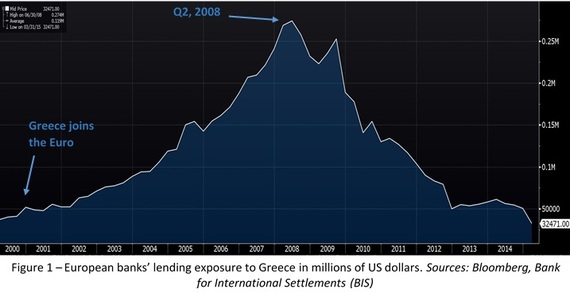

It is often overlooked that Europe’s deficit countries would not have been able to recklessly borrow if the surplus core countries of the eurozone-Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France, and others-had not recklessly lent (Figure 1).

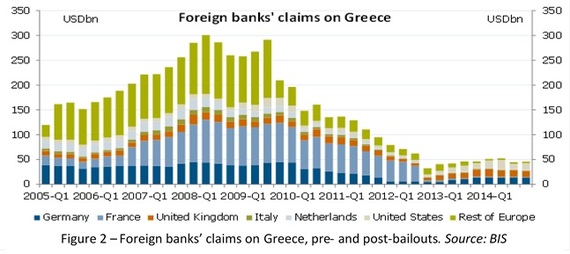

Indeed, outside of Greece, the biggest exposure to Greek government debt and Greek banks’ liabilities was in the financial institutions of the EZ core (Figure 2). The 2010 bailout prevented a Greek collapse that would have permeated widely across Europe’s financial institutions, especially those in the surplus countries. The lack of recognition of this fact has led to political acceptance/determination in surplus countries of the harsh austerity conditions that have been imposed upon the EZ periphery countries in the current (deflation-biased) recovery framework.

Had Greece been allowed to fail and financial contagion spread across the eurozone, the politics of the surplus countries likely would have changed drastically, much like we’ve seen in the deficit countries–the rise of Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, and others. Surplus countries would have clearly felt the economic pain as their banks and financial institutions began to fail, get bailed out, or get nationalized. EZ core countries would have had to wind down their surpluses to protect their own economies and spur local demand; certainly, surplus country governments would not have been able to get off blame-free if the Greece contagion had been let loose. The voters of core EZ countries would have demanded more action–much more than their demands today of simply making the deficit countries pay for their own ails.

Had the IMF let Greece fail, its contagion would have left Europe in an even greater recession, but perhaps that would have allowed for a greater recovery on the back of European policymaker consensus and orientation towards increasing eurozone-wide demand–and thus, growth. Germany and others have resisted changes to the eurozone’s structure that would allow the EZ to be better prepared for future recessions because of concerns over moral hazard behavior among deficit countries. Their concerns are that creating more effective government backstops and risk-sharing among EZ countries will provide the EZ’s deficit countries with an implicit government guarantee–allowing them to resume their fiscal misbehavior and cause another crisis. In reality, it is the surplus countries’ own financial institutions–which lent recklessly in the lead-up to the crisis–that received the implicit government guarantee.