By Andrey Sushentsov, Associate Professor, Moscow State Institute of International Relations

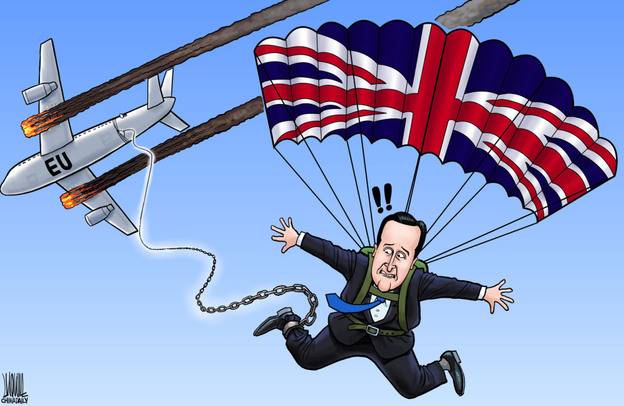

It is puzzling to observe from Moscow the ongoing Brexit debate in Britain. The UK press, some experts and even politicians seem to propel Russia and Vladimir Putin personally to be among the most interested parties in the issue. Both critics and proponents start their analysis of a Brexit’s international implications with the notion that “Putin will be rubbing his hands”.

The argument behind this logic is very vague, simplistic and often ridiculous. For Russia, the possibility of a Brexit has the same basic implication as for everybody else in Europe and the world– uncertainty. Both the economic and global political consequences of Britain leaving the EU are difficult to predict both for Russia and the EU. And Russians – historical pessimists – assess that negative consequences will be more widespread if the European status quo shatters. That is why Russian leaders have so far refrained from commenting on Brexit.

What the “rubbing-hands Putin” logic omits?

First and foremost it is the economic interdependency that connects Russia with both the EU, and the UK. In Russian foreign trade, finance and investment links with the EU continues to be number one priority.

For several decades, the EU has been the leading trade partner for Russia, with 46% of its foreign trade share in 2015 – a total of 249 billion USD. Granted, Britain has a marginal role in Russia’s trade with the EU, and there are little to no joint production chains. However, Brexit will no doubt impact the whole of European trade and inflict the most significant harm to Russia’s top economic partners in Europe – the Netherlands and Cyprus. London-based Global Counsel’s report indicates these countries as the most highly exposed to Brexit consequences. Russian dependency on Cyprus’ off shore financial services forced Moscow to assist Nicosia in financial turmoil of 2008-2011, providing it with a 2.5 billion euro preferential credit.

There are doubts that Brexit will diminish London’s position as the top European financial center, however nobody knows exactly what will happen. For Russia, it is a matter of significant economic importance. Moscow’s foreign direct investments in the UK in 2014 amounted to 9.1 billion USD (with another 60.9 billion USD in British Virgin Islands). According to Russian data two other important destinations of Russian FDI’s are Cyprus (19.7 billion USD) and Netherlands (19.1 billion USD).

Russian foreign currency reserves, the third largest globally, are largely invested in foreign government securities, with Britain’s share 9.4% and the EU share around 62%. More importantly 41.5% of Russian reserves are nominated in Euros. Russian foreign reserves – currently at 360 billion USD – are expected to depreciate if Brexit hurts economically Britain, the EU or both.

Lastly, leading Russian companies use London as the prime European financial center. Most of Russian majors came to the London Stock Exchange (LSE) in late 1990s. Currently companies from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) constitute up to 17% of total trade in London, featuring Russian majors Gazprom, Rosneft, Lukoil, Sberbank, Tatneft, Megafon and Rusagro. Five Russian companies are in the LSE’s top 20, with Gazprom in the lead for several years. If Britain becomes a less important financial center in the event of a Brexit, Russian companies will have to change their public offering priorities. It is indicative that in recent years Russians have more eagerly entered the Shanghai and Hong Kong Stock Exchanges, and some have delisted their shares from LSE.

If economic repercussions of a Brexit for Russia can be somehow calculated, it is much harder to estimate its international political implications.

The current fragmentation of the EU is an ongoing slow surprise for Moscow that it was not prepared for and that was in no way a result of Russia’s doings. Actually, Russia was expecting the EU to eventually consolidate and become an independent global player free of US patronage. Besides, it is easier to trade and relate with the single body in Europe, not facing the perspective of having 28 representatives at the table discussing minor trade or visa issues. This was the basis of the idea to build a common space “from Vancouver to Vladivostok”, which Moscow still nourishes. By creating the Eurasian Economic Union, Russia intended to gain leverage over the EU and at some point in the distant future “integrate integrations”, merging the EEU with the EU. What will happen with this perspective after Brexit is unclear. The big challenge for Moscow is to think this through.

It is clear that Brexit will bring a new balance of power in the European Council. How would German-French competition look like without Britain covering up disagreements? Will Paris and Berlin merge closer?

Alternatively, Europe will face a stronger Germany that will turn EU into its own project, introducing fiscal union, facilitating Grexit and a few other exits from the Eurozone. In this perspective the EU will not be a union of 27 nations anymore, but a “Germany plus”. Is this good or bad news for Russia? That is an open question, but if history is a reference – there are reasons to avoid this eventuality.

The most important unknown is what role Britain would choose after Brexit? Not many people in Russia believe it will aspire to be an independent global player. To stay relevant and avoid territorial integrity problems London can opt to build a stronger alliance with the US. A few pro-American states in Eastern Europe can join such a new political bloc. No doubts, sanctions-related activity would drive the Russians away from cooperation with a Anglo-Saxon alliance that would build a “Polish-Baltic wall” on the border with Russia. On the other side of Europe the core EU countries – Germany, France, Italy, etc. – can consolidate a block that will tend to normalize ties with Russia. In a generation, we can face two different Europe’s that will compete with and challenge each other – hardly a future any of us want.

No doubt, Brexit will inflict economic harm on both the UK and the EU. Eventually it will affect Russia, forcing its companies and government economists to change financial priorities and seek for a different safe haven. Incidentally, it can result in diminishing Russian presence on European financial markets and its reorientation toward Asian ones, thus strengthening Russia’s “turn to the East”.

An English proverb states “measure twice, cut once”. Its Russian equivalent is as old as the British one. It says, “Measure seven times, cut once”. Brexit is a highly uncertain enterprise with long-term widespread repercussions. If I were British, I would follow the Russian proverb on this occasion.

The opinions articulated above represent the views of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address the pressing foreign, defence, and security policy challenges of our time.