By Timothy B. Lee

If you’ve used Facebook on a desktop or laptop computer, you might have noticed the “trending topics” box in the right rail. While the title gives the impression that the list is automated, a Gizmodo piece last week reported that a group of 20-something journalists help algorithms choose which stories appear in this box and write headlines and brief summaries for them:

hey. look what’s trending on Facebook. pic.twitter.com/8rWNavwq4p

— Kashmir Hill (@kashhill) May 9, 2016

And on Monday, Gizmodo dropped a bombshell: A former member of this team alleged that the trending topics team was systematically skewing the results to favor liberal viewpoints. According to Gizmodo’s source (who declined to be named, so it’s hard to verify his claims), Facebook’s trending topics team tended to be dismissive of stories that came from right-leaning news outlets such as Breitbart, Washington Examiner, and Newsmax — waiting instead until more mainstream news organizations like the New York Times or the BBC covered them.

“I’d come on shift and I’d discover that CPAC or Mitt Romney or Glenn Beck or popular conservative topics wouldn’t be trending because either the curator didn’t recognize the news topic or it was like they had a bias against Ted Cruz,” the former Facebook contractor, who identified himself as a conservative, told Gizmodo.

This has triggered predictable — and justified — consternation among online conservatives. “It is beyond disturbing to learn that this power is being used to silence viewpoints and stories that don’t fit someone else’s agenda,” argued a press release from the Republican Party.

Facebook insists that the allegations are untrue. “There are rigorous guidelines in place for the review team to ensure consistency and neutrality,” wrote Facebook’s Tom Stocky late on Monday.

Behind this story is a deeper question that unnerves everyone — including established, mainstream outlets — in a media ecosystem that’s increasingly dependent on Facebook’s whims: The company’s power is vast, and that power is not always deployed in ways that are transparent and accountable.

Mark Zuckerberg has always said he wants to build Facebook into “a utility,” and he’s arguably succeeded. But utilities, because they’re so important, are highly regulated. Facebook is approaching utility-level importance, but it answers to no one — not even, given Zuckerberg’s control of the company, its shareholders.

The irony here is that the government used to more actively regulate large media companies to prevent them from abusing their power. Conservatives were skeptical of these policies, and they have largely gotten their wish online. As a result, we now have an unregulated free market for internet content. And it has put a lot of power in the hands of left-leaning CEOs like Zuckerberg.

The feds used to strictly regulate the power of big media organizations

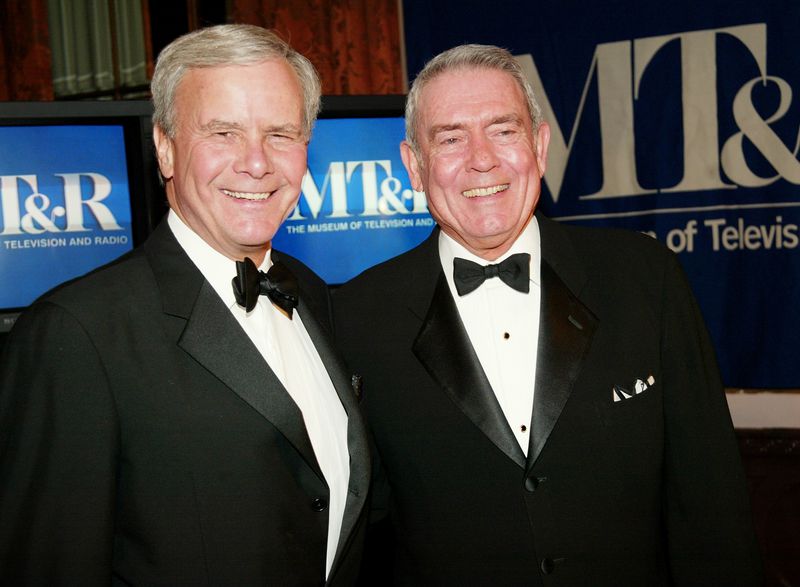

Photo by Evan Agostini/Getty Images

Tom Brokaw and Dan Rather never had as much influence over the news as Mark Zuckerberg does today.

During the second half of the 20th century, broadcast media and daily newspapers played a dominant role in the information diets of ordinary Americans. A typical American city might have one or two daily newspapers and three or four local television stations. There might also be a couple dozen radio stations, only a few of which carried significant news programming.

Strictly speaking, these weren’t the only sources of news. But they had enough influence that the Federal Communications Commission established a complex set of regulations designed to ensure that influence wasn’t abused.

For example, a 1975 regulation made it illegal for a company to own a major newspaper and a television station in the same market. Also, in the late 20th century, no company could own television channels reaching more than 35 percent of the country — a cap that was bumped up to 45 percent in 2003.

In 1949 the FCC instituted the Fairness Doctrine, a controversial rule requiring broadcasters to give “equal time” to opposing points of view on controversial issues. The repeal of this rule in 1987 paved the way for talk radio hosts like Rush Limbaugh, who are known for offering a strongly one-sided point of view to listeners.

These rules existed because regulators believed it was dangerous for any single company to exercise too much influence over the national political conversation. By carefully limiting media consolidation, the FCC hoped to provide room for a diversity of voices to be heard.

But in the past couple of decades, this approach has fallen out of favor. Conservative policy experts have argued that the proliferation of media organizations has made it unnecessary for the government to micromanage the structure of the media sector.

“Americans are in no danger of seeing their news and information monopolized, least of all by newspapers,” wrote the Heritage Foundation’s James Gattuso in 2008, arguing to liberalize the broadcast-newspaper cross-ownership rule. “Rather than increased concentration, recent decades have brought an historic expansion of information sources and their diversity.”

And conservatives have largely won this argument. Today, cable television networks and the internet are much more lightly regulated than the broadcast media giants of yesteryear.

The internet changed the nature of media power

In the 20th century, power came from owning the means of distributing content — like a printing press or a broadcasting tower. If your town only had two daily newspapers and four television channels, the companies that controlled those six outlets had outsize influence over public debates.

Not anymore. Thanks to platforms like Medium and YouTube, anyone can distribute text, audio, and video content worldwide for free. But being able to publish something globally isn’t the same as getting a lot of people to read it. Instead, power has shifted to companies like Google, Twitter, and especially Facebook that help their massive audiences filter online content.

In some ways, these new media platforms are more powerful than old-fashioned media companies have ever been. Facebook, for example, has a billion daily active users — a far larger loyal audience than any television network or newspaper has ever had.

BEING ABLE TO PUBLISH SOMETHING GLOBALLY ISN’T THE SAME AS GETTING A LOT OF PEOPLE TO READ IT

And these companies’ role as the internet’s gatekeepers gives them a lot of power over other media companies. Facebook and Google each account for double-digit percentages of the traffic of many online news organizations. Most news sites spend a lot of time thinking about how to maximize the traffic they receive from Google and Facebook. This leads to articles like the Huffington Post’s infamous 2011 article, “What Time Does the Superbowl Start?” (and its many imitators), whose entire purpose was to get a good ranking on Google’s search results for people wanting to answer that question.

Similarly, the curiosity gap headlines innovated by Facebook-first publishers like Upworthy and now emulated all across the internet (“You’ll never believe what happened when…”) are an effort to generate high click-through rates and thus win favor from Facebook’s content algorithms.

But in other ways, Facebook and Google are not as powerful as the media giants of the past. While many people use Facebook, there are many, many other sites that help you find interesting content. All of them are available with just a couple of clicks. And while Facebook and Google can drive traffic to content they think is worthwhile, they have very little power to stop the spread of content they don’t like; people can always share using other platforms like email or Reddit.

The “trending topics” snafu illustrates both the extent and the limits of Facebook’s power

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Gizmodo’s report that a small group of Facebook contractors may have been manipulating users into reading more left-leaning content highlights just how powerful Facebook has become. There’s no evidence that Mark Zuckerberg or anyone else in Facebook’s leadership made a conscious decision to skew the trending topics box in a left-wing direction. Yet so many people spend so much time on Facebook that even a small shift in the platform’s approach could have a big impact on what people read online.

And in principle, Facebook could do a lot more. People spend most of their time interacting not with the trending topics box at the right of the screen but with the news feed in the center. If Zuckerberg wanted to really shape people’s media diets, he would have his engineers tweak how the newsfeed works to steer people toward favored content.

A particularly chilling example, suggested by the Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer, would be for Facebook to turn itself into a turnout operation for Zuckerberg’s favorite political candidates. Facebook’s own experiments have shown that telling people their friends have voted increases the odds that they’ll vote too. If Facebook showed those buttons only to Democrats — and it would be easy for Facebook to figure out who was likely to be a Democrat — it could swing a close election.

But the reaction to Gizmodo’s latest story also illustrates that Facebook’s power could prove relatively fragile. The news that Facebook may have been manipulating the trending topics box has rocketed around the conservative internet, generating a volume of bad press that has to hurt even for a company of Facebook’s size.

And the current furor is tiny compared with the backlash that would occur if it were revealed that Facebook management was deliberately trying to manipulate the political system. That could easily trigger a broad conservative boycott of Facebook and could even create an opening for one of its rivals to gain market share at Facebook’s expense.

Precisely because the danger of backlash is so high, it’s unlikely that Zuckerberg will ever be so ham-handed as to explicitly censor or promote content on an ideological basis — or to try to directly manipulate an election. But even subtle tweaks to Facebook’s algorithm can have profound effects. For example, Facebook’s current model has contributed to the internet’s “filter bubble” effect, in which people disproportionately read content they agree with, giving a boost to candidates with extreme views.

Facebook’s power is a real concern

It wouldn’t make sense to try to directly regulate the behavior of major internet platforms. Not only would good regulations be fiendishly difficult to write, but there’s a good chance they’d get struck down on First Amendment grounds.

Nevertheless, it’s worth taking seriously the dangers that can come from excessive concentrations of power and thinking about ways to limit that power. One obvious way to do this is by scrutinizing mergers more carefully. Back in 2012, for example, the Federal Trade Commission quickly approved Facebook’s proposal to acquire Instagram, which quickly became one of the largest social media sites on the internet.

It’s probably not fair to blame the FTC for missing the significance of this merger, since Instagram has grown fast over the past four years. But federal regulators should think harder the next time Facebook (or a large rival such as Google) wants to acquire a fast-growing online platform like Instagram.

There’s also room for users to engage in self-help here. If you find it creepy that a secret Facebook algorithm has so much influence over your reading habits, there are a lot of other ways to find news stories that are less prone to manipulation. You can subscribe to your favorite sites using an RSS reader. You can spend more time on Twitter, which shows posts in a more chronological order, leaving less room for manipulation. Or you can browse the web the old-school way: bookmarking the homepages of your favorite news sites and visiting them directly.