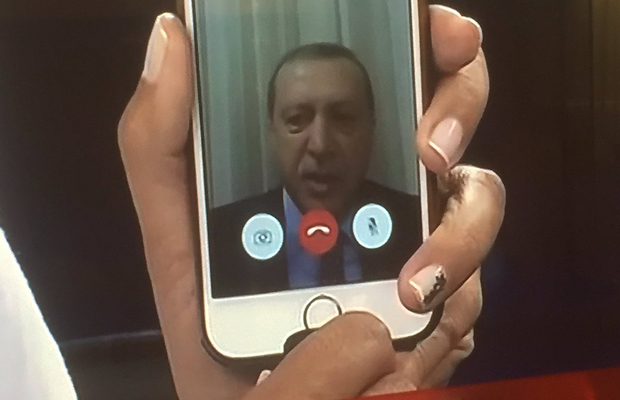

Turkish coup leaders sought to defeat the flow of information, but with an iPhone Erdogan’s extraordinary address helped defeat them

By Graeme Baker, Middle East Eye

It is a moment that will perhaps go down in history as the first coup foiled via iPhone.

No doubt aware that state broadcaster TRT was in the hands of army rebel, having seen bridges over the Bosphorus lined with their foot soldiers and tanks heading for Ankara’s parliament, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan did the extraordinary.

On CNN Turk, an arm of the US-based broadcaster, a telephone was held to the camera by the presenter, a lapel a microphone pressed close to the speaker, and Erdogan’s face came into focus. FaceTime with Erdogan was under way.

“We will overcome this,” Erdogan said, urging his supporters to take to the streets to protest against the attempt to overthrow him.

“There is no power higher than the power of the people.

“Go to the streets and give them their answer… I am coming to a square in Ankara. This was done from outside the chain of command. Those who are responsible, we will give them the necessary punishment.”

Up until that point late on Friday, the coup plot appeared in the ascendency. Within minutes of Erdogan’s brief appearance, social media sites such as Twitter began to fill with pictures of civilians on the streets of Istanbul and Ankara, shouting down the coup and its supporters.

Control of the airwaves is crucial for any attempt to seizing power by force, and the coup’s leaders thought they had it: A statement, on TRT, apparently delivered at gunpoint, said that a “peace council” was in full control of Turkish government, that martial law was in effect, and that a new constitution was being prepared.

Erdogan was having none of it and nor were his supporters, nor those who opposed the military takeover. Within hours, the attempt to remove the elected government was in disarray.

But not before bloodshed and violence on the streets of Turkish cities.

Social media again played its part in relaying the events as they happened – the “livestream” service Periscope ran countless feeds of protesters marching on coup strong points, retaliations by troops, and in the final hours to civilians standing on tanks, and soldiers with machine guns surrendering to crowds armed with phones.

And by the early hours of Saturday morning, TRT, itself a global operation with offices in London, was back on Twitter posting under the hashtag #failedcoup.

In coups of the past, such information was difficult if not impossible to obtain. In Turkey on Saturday it flooded the internet. And that, perhaps, is where the putsch faltered and failed.

Ali Turksen, a former colonel in the Turkish military, told Middle East Eye that Erdogan’s appearance via FaceTime was the catalyst for the counter-coup. The people heeded his message and took to the streets, he said.

“Once the people decided to heed his call and took to the streets, the coup was over,” he added, but stressed Erdogan needed the people’s support.

Turkey’s mosques also played their role in launching the counter-coup. Shortly after 1am on Saturday, calls to prayer could be heard blasting from many of Istanbul’s minarets, hours before dawn. It was a call to protest.

Twitter has “gone dark” in Turkey on numerous occasions to prevent dissent.

Powerful laws threatening prison for insults against the state have put many in jail.

Newspapers have been taken over by the state, and journalists imprisoned for, among other things, endangering national security with scoops on Turkey’s activities in the neighbouring civil war.

The use of FaceTime by the president will go down as a defining moment of the attempt to topple him.

But it also shows how Erdogan understands the power of information in an age where the coup plotters found, to their cost, it is almost impossible to control.