By ELENI KONIDARI, Open Democracy

In his historical visit to Greece earlier this month, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan unexpectedly brought up the Treaty of Lausanne, condemning Greece for violating it with regards to the lives of the Muslim minority in Western Thrace. Therefore, he asked for the Treaty to be revised so that it becomes relevant again.

Although Erdoğan brought the discussion about Lausanne to an international audience (Financial Times, The Guardian, The New York Times, BBC to name but a few) the Lausanne box is always open within the local politics of Western Thrace, and on various occasions also comes into the public realm at a national level in Greece when there is discussion around the Muslim minority in Thrace, Turkishness or Islam in Greece.

The Treaty of Lausanne is an international law dating back to 1923. A Peace Conference was held in Lausanne at the end of the Greco-Turkish war in 1922 that also marked the birth of the Republic of Turkey. In an era of radical nationalism, the first agreement in Lausanne was a compulsory exchange of populations – a mild yet, at this scale, unprecedented means of ethnic cleansing: ‘Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion’ had to move to Greece and the ‘Greek nationals of the Moslem religion’ had to move to Turkey.

From the exchange were exempted the ‘Muslims’ of Western Thrace and the Greek-Orthodox from Istanbul, Gökçeada and Bozcaada, creating the respective minorities in either country. Due to a series of discriminatory measures and a pogrom followed later by expulsions, the number of Greek minority members in Turkey has dramatically diminished to virtual non-existence. The Turco-Muslim minority group in Greece, a largely rural population in the North of the country, has kept more or less its number, having suffered nonetheless decades of overt institutionalised discrimination that was only officially denounced in the 1990s.

Nikos Kotzias, the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs, notorious for his nationalist background, tried to capitalise on Erdogan’s statement to further the Greek nationalist, Turkish-phobic rhetoric. Meanwhile, a few days after Erdoğan’s comments about the rights of people in Western Thrace, a boat arrived on the Oinouses island in the Aegean with 32 Turkish nationals on board seeking political asylum in Greece. If we are concerned about minority rights’ protection and struggle and want to break with hypocrisy, better not to be distracted by what is preached from the top but rather look at how international law operates in the vernacular in the concerned communities and review what needs to be changed at a grassroots level.

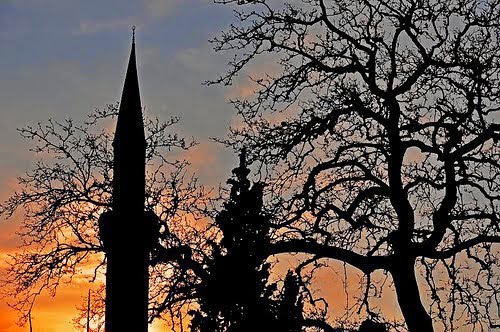

In the aftermath of the Peace Conference in Lausanne, Western Thrace became a borderland; both fixed and fluid. Fixed by the frontier that the river Evros/Maritsa poses between the two states and the imposition of a limit, a border. Fluid by its character as a world-in-between – a melting pot within a landscape of cultural trauma. Eyerman (2001) defines cultural trauma as ‘a dramatic loss of identity and meaning, a tear in the social fabric, affecting a group of people that has achieved some degree of cohesion’. The minority and majority groups in Thrace as well as the ‘Greek nation’ as constructed in mainstream narratives have all experienced through Lausanne ‘a dramatic loss of identity and meaning’.

The Greek nation, as imagined, has experienced a biblical loss. In Greece, the events prior to the Peace Conference are memorialised as the ‘Asia Minor Disaster’. In Western Thrace, a group glued under the collective identity ‘Muslim minority’ experienced a radical challenging of their belonging to their homelands. Thracian Muslims have been the historical residents of the region and they also enjoyed collectively, for centuries, a majority identity as Muslim subjects in the Ottoman Empire. After Lausanne, they turned into alien subjects.

On the other hand, the newcomers, the Lausanne-made refugees from Turkey, forcibly uprooted from theirs and their ancestors’ lands, came to a region where they had to establish themselves vis-a-vis people who felt tightly linked to the trauma they suffered. It was the Turks, the Muslims, that had to be their neighbours, simultaneously living reminders of a potential re-loss; the foot of Turkey in Greek territories.

The Treaty of Lausanne in Western Thrace has been experienced in the Thracian society at large as a story of victimisation and as such has defined the way citizenship and social equality has been experienced by both sides in the area: minority and majority.

For the minority group, Lausanne constitutes what they often call their ‘birth certificate’ and ‘Constitution’. Living in a country that does not deal well with minorities, the group is tightly anchored to the one international law text that forces the Greek government to acknowledge their existence and to grant them rights.

Symbolically, the Treaty of Lausanne is a powerful totem in the Freudian sense. It operates as a sacred symbol which represents the origins of the minority group and functions as their guide and rescuer. Its sacred character makes it untouchable, especially because the group’s collective identity derives from the shared fate that unites all minority members in relation to it.

The Treaty of Lausanne stated the rights conferred to the non- Muslim minorities in Turkey and specified that the same rights should be conferred to the Muslim minority in Greece. This simple sense-making quote, that the two minorities should enjoy the same rights, has been used ever since by both the Greek and Turkish authorities as a way to equally mistreat the minorities and to tie their destinies to the Greco-Turkish relations.

This way Lausanne opened an arena for dependency politics in regard to the minorities. It has also opened a dead-end discussion that goes no further than highlighting the atrocities and violations in both camps to justify oppression and limit the dialogue to the tight Lausanne boundaries: a claustrophobic vacuum that is perceived as the only space to guarantee protection, when in fact very little has been achieved. Greek nationalists use Lausanne to deny rights, whatever can be deniable.

Minority patriotism and Turkish nationalism in Greece use Lausanne to claim what is claimable. And the battle goes on in a vicious cycle. It has been a small elite within the minority group in Thrace that mainly advocates for the rights of their people responding to the state’s rhetoric by adopting the same one in the same terms.

This has not only had the effect of reproducing the oppressive for the group ideology – nationalism – but also in a second degree oppressing the rights of individuals that do not identify as Turks within the minority. What most of the ordinary people of minority labelling agree with in Thrace, is that this situation of conflict continues because it confers both monetary and symbolic capital to many. Nationalism operates as a profitable business locally: play the game well and you can win money, status, jobs.

I don’t know if the Treaty of Lausanne is anachronistic. I am, however, certain that what needs to be revised is the anchoring of people to the Treaty in order to claim equal and free lives. If it is understood that neither the Greek nor the Turkish state have a tradition in truly wanting to protect minorities, the struggle for change has to be reinvented at its grassroots. At the community level, a law that has symbolically being synonymous to trauma and dependency and springs directly from an era of radical nationalism, can only establish, as it has done so far, a long-term sense of powerlessness.

The more people experience their identities through victimhood, the more they are looking for a saviour, the more powerless they will continue to be. At this level of community discourse and lived experience, Lausanne is not liberating but rather a barrier to building a radical new way of establishing minority rights in Greece, beyond the bubble of Western Thrace, that need not only be limited around religious, linguistic and ethnic otherness but the very essence of citizenship.