“We’ll strangle this force at birth,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdodan warned Syrian Kurdish leaders this week, in a message aimed directly at the White House. He was referring specifically to the Kurdish military force the United States wants to set up in Syria as a kind of border patrol along the Turkish-Syrian border.

The force, expected to number some 30,000 fighters, isn’t really a new army. At least half its members are already operating in northern Syria as part of the Syrian Democratic Forces, a militia comprised of Syrian Kurds and Syrian Arabs which America set up more than two years ago to fight the Islamic State.

That militia’s approximately 15,000 members, who were trained and funded by Washington, had impressive success against Islamic State and became the most important “American” ground force in that war. Now that Islamic State is defeated and Syria’s civil war is winding down, the Kurds want to continue ruling the areas they liberated from the Islamic State and annex them to the Kurdish autonomous zone they created in northern Syria.

The new border patrol’s other 15,000 troops are supposed to join over the next two years, during which America plans to leave 2,000 “advisors and trainers” in Syria.

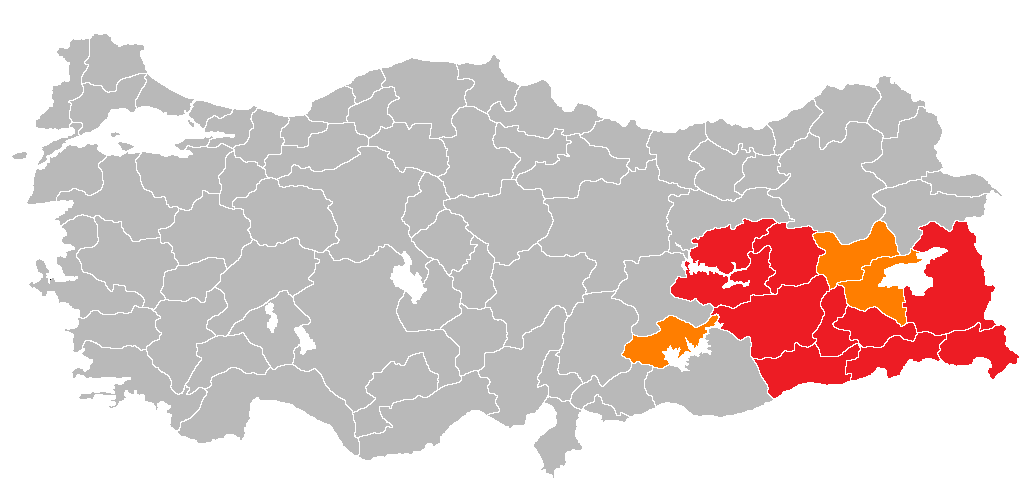

This idea frightens Turkey, which envisions its southeast border becoming an autonomous Kurdish canton with its own army backed by Washington. Therefore, it recently beefed up its own forces on the Syrian border in preparation for invading the Kurdish-controlled area around Afrin and Manbij.

Turkey regards the prospect of Syrian Kurds on its border much as Israel does the prospect of Iranian forces in Syria on its border. Just as Israel said it won’t permit it, Turkey is making clear that it won’t permit Kurdish forces near its border either.

If a diplomatic solution to this crisis isn’t found soon, Syria is likely to see a new war erupt – not a hot war between Turkish and Kurdish forces, but a diplomatic war between Turkey and America, which could cause real damage to relations between these two NATO members.

Erdogan’s advisor Ilnur Cevik warned this week that America was risking a Turkish invasion of Syria “on the model of its invasion of Cyprus in 1974.” Then, too, Cevik wrote in the pro-government newspaper Sabah, the West didn’t take Turkey’s warning seriously. “Today, Turkey is stronger and has greater resources, while the Americans are losers worldwide,” he added.

This warning is a bit surprising, since a rift with Washington would hurt Turkey far more than America. Washington, for instance, could impose sanctions on the Turkish bank whose deputy general manager was convicted of circumventing sanctions on Iran. It could also sanction Turkey for buying S-400 missiles from Russia, which are made by a company on the U.S. sanctions list.

Turkey is militarily capable of invading and conquering Kurdish-held areas around Afrin and Manbij, which are near the Turkish border. But though Turkey is aiming its arrows at Washington, the areas in question are actually under Russian protection. Russia even invited Kurdish representatives to a conference in Sochi next month slated to discuss de-escalation zones in Syria and a diplomatic solution to the war. It did this despite vehement objections by Turkey, which views the Kurdish organizations as terrorist groups.

Moreover, Syria’s Assad regime, backed by Russia, reached agreement with the Kurds to establish a Kurdish security zone around Manbij after Turkey threatened to conquer the city. Following the latest threat, the regime warned Turkey it would view such an invasion as a violation of its sovereignty, so its own forces would join the fight.

Does this warning also reflect Russia’s view? That’s what Turkish Chief of Staff Hulusi Akar and intelligence chief Hakan Fidan are trying to find out in their current trip to Russia. They want to know how Russia would react to a Turkish invasion, and perhaps even receive Russian “permission” to fight the Kurdish militias, just as Israel received Russian “permission” Israel to attack Hezbollah targets in Syria.

Russia isn’t likely to agree to a Turkish invasion, and it’s not clear whether Turkey would act without Russian permission. Moscow does oppose dividing Syria into cantons, but like the Assad regime, it recognizes that Syria’s stability depends partly on cooperation with the Kurds. Thus agreeing to a Turkish invasion might thwart the diplomatic solution Russia seeks.

In one Russia scenario, the Kurds would enjoy political and cultural autonomy while remaining part of Syria and obeying the new Syrian constitution slated to be drafted after the war. This scenario would force Russia to block Turkish ambitions to destroy the Kurds’ military force, but also to reach agreements with the Kurds about their operations along the Turkish border.

It would also force the Kurds to decide how to continue their diplomatic game with both Washington, which funds and arms them – effectively ensuring their military survival – and Russia, which offers them partnership in the diplomatic process. This is a critical decision, because American support for other militias has proven unstable over the long run. And judging by what U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said this week, Washington doesn’t intend to establish a Kurdish army. He told his Turkish counterpart, Mevlut Cavusoglu, that the new force won’t be an army, but a local force to protect the Kurds themselves.

Moreover, Washington has said Afrin and Manbij won’t be included in the new force’s area of operations. In other words, it won’t intervene if Turkey invades them. But Turkey said it wanted deeds rather than words – specifically, taking back the weapons America gave the Kurds, which Ankara claims America promised to do.

The Kurds’ dilemma isn’t only about which superpower to rely on. There’s also no agreement within the Kurdish region on how to continue running their geographically noncontiguous territory.

The dominant political force, the Democratic Union Party, doesn’t represent all Kurds in northern Syria, and despite its name, democracy isn’t one of its salient characteristics. It tolerates no criticism, and some of its opponents have been jailed or fled. Its military force, the Popular Protection Units, has failed to unite the Kurdish regions of northern Syria, and it is also at odds with Kurdish parties outside Syria, like those running Iraqi Kurdistan.

Thus the party’s desire to lead a united Syrian Kurdish zone must overcome not just the geographic split but also internal political rivalries. Syrian Kurdish pundits even say that when Syria’s civil war ends, a Kurdish civil war may erupt within Syria, just as happened in Iraqi Kurdistan.

But even before all these issues are addressed, the Syrian Kurds may need to decide whether and how to fight a Turkish invasion, should one actually occur.