By David Lepeska, Ahval

The news last week that Hakan Şükür, likely Turkey’s best-ever footballer, had been reduced to driving an Uber and selling books to make ends meet in the United States came as a shock to many Turks, and highlighted the lightning-fast decline of the Gülen movement.

In 2013, Şükür was a Turkish sporting icon and a parliamentarian for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which for more than a decade had been allied with Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen, a fellow Islamist.

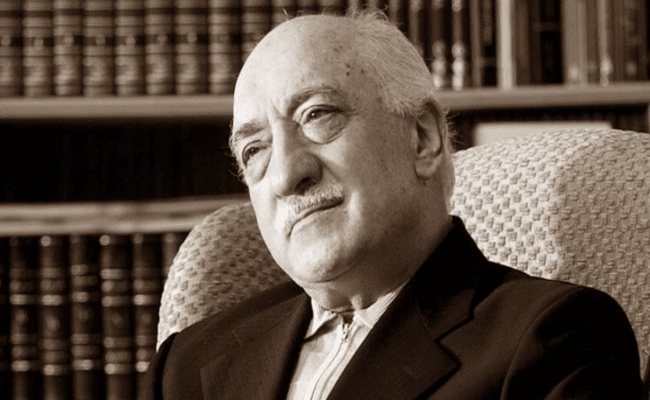

Back then, the Pennsylvania-based Gülen had millions of followers worldwide. His network ran thousands of schools around the world, businesses worth billions of dollars and a handful of publishing and media outfits. The movement also had thousands of members working within Turkey’s judiciary, police forces and military.

The AKP joined forces with the Gülenists to subdue the Turkish military in two long-running, widely questioned coup-plot trials, “Ergenekon” and “Sledgehammer”, which put hundreds of mainly secularist military officers in prison.

Then came the failed coup of July 2016, in which some 250 were killed. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan blamed the Gülenists for the plot and labelled it a terrorist group (known in Turkey as FETÖ). As Istanbul mayor in the 1990s, Erdoğan officiated at Şükür’s marriage to his first wife. Now police have issued a warrant for Şükür, who has been linked to Gülen, and seized millions of dollars of his assets as part of a series of nationwide purges.

More than 150,000 civil servants have been dismissed and some 50,000 alleged Gülenists thrown in jail. Turkey has forced the closure of hundreds of Gülen schools and businesses around the world and pressured foreign governments, mainly African and former Soviet states, to hand over more than 80 Turkish citizens with links to Gülen.

But in Europe, thousands of exiled Gülenists have generally received a warm welcome and been allowed to carry on with their lives. This has emerged as a source of tension for Turkey, particularly with Germany, where Turkish officials have said that some 14,000 Gülenists now live. In 2018, an AKP spokesman said Turkey expected Berlin to take concrete steps against the Gülen movement and extradite thousands of its members.

Kristian Brakel, Istanbul head of Berlin-based think tank the Heinrich Boll Foundation, said there was little German authorities could legally do.

“When it comes to the Gülen movement, the majority of people who are with the movement in Germany are people who of course have no criminal record whatsoever,” he told Ahval in a podcast. “That doesn’t mean the organisation is free from blame, but it becomes very difficult to sentence individuals who have not committed a crime in Germany.”

Tens of thousands of suspected Gülenists have fled Turkey, but still the purge continues. Turkey arrested another 176 soldiers last week, adding to the thousands of officers and servicemen detained for links to Gülen.

“Erdoğan smashed the whole organisation, after they have been together for years,” exiled Turkish journalist Can Dündar, former editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet newspaper, told Ahval in a podcast. “Their power has disappeared all of a sudden.”

The evidence suggests that at least a handful of Gülenists played key roles in the failed coup. But it is more than likely that the vast majority of the movement’s members had no idea about the plot. Turkish citizens face a steady stream of pro-government media coverage, and as a result largely agree with the AKP view.

Exiled or in Turkey, in jail or living freely, today many members of the movement are, like Şükür, just looking to survive. Few global organisations have fallen as hard and as fast as that of Gülen.

“The movement is still breathing because in many Western countries people are still participating in its activities,” said Ahmet Kuru, political science professor at San Diego State University who was previously connected to the movement. “Still, we might say it is dead in Turkey, and even globally, as it does not have a bright future.”

Meanwhile, Gülen himself is nearing 80-years-old and has appeared frail in recent years. He is widely seen as a stubborn figurehead who remains unwilling or unable to admit his mistakes.

“We haven’t heard anything from Gülen himself, about what was going on, what happened, what was wrong and what was right,” said Dündar. “If it’s such a powerful organisation, there must be self-criticism.”

Gökhan Bacık, a political science professor at the Czech Republic’s Palacky University and an Ahval columnist, takes a similar view. “Let alone aiming for change, the movement does not appear to even recognise it has any problems,” he wrote in a column this week.

Gülen has denied any involvement in the coup, but said little beyond that. Instead of coming clean and beginning to move forward, Bacık pointed out that the organisation had allowed key figures accused of criminal activity, like Barbaros Kocakurt and Cevdet Türkyolu, to remain in their posts, while other leaders had been in place since the 1970s.

Several Gülenists have launched organisations focusing on human rights, including one that sponsored anti-Erdoğan ads during last year’s United Nations summit, and another that mainly reports on Turkey’s violations of the rule of law.

“Now they are defending the principles we have been defending for years,” said Dündar, who found it comical that former partners in questionable democratic practices, the AKP and the Gülen movement, now view each other as anti-democratic. “They just realised the danger of each other, which we’ve been aware of for years.”

The AKP government may now be helping other Islamic sects emerge to fill the void left by exiled Gülenists. Religious orders have been a powerful force in Turkey for decades, with the most significant being the Naqshbandi, a conservative brotherhood with several branches. The AKP sprang from one branch, and a shadowy group called the Menzil hails from another.

In their book “Metastasis”, published last year, Turkish journalists Barış Terkoğlu and Barış Pehlivan argued that the government has since 2014 been replacing Gülenists with members of the Menzil group. Independent Turkish outlet T24 recently reported dozens of appointments in the police that referenced Menzil membership, and said the group was present in all Turkey’s 81 provinces.

The Menzils’ main objective is self-interest; they seek power and influence first and foremost. Menzils also run sizable businesses, schools abroad, publishing outfits and a university.

“The network built by the Menzil bears an uncanny resemblance to the one the Gülenists once commanded,” Istanbul-based journalist Killian Cogan wrote in Foreign Policy last week. “Over the past few months, the acronym METÖ – a play on FETÖ – has widely circulated in Turkish media.”

But analysts say the Menzil has nowhere near the reach and influence of Gülenists at their peak, nor is it as disciplined or tightly connected as the Gülen movement. The Gülen movement’s strict authoritarianism, in fact, now appears to be its Achilles’ heel.

“The Gülen movement is an organisation in the true Turkish style, and that means that it brooks no dissent,” wrote Bacık, adding that Gülen has never been accountable. “The group’s successes are attributed to him, but when it comes to its failures, his involvement is denied.”

Bacık said that Gülen never cared much for the civil side, making a priority of infiltrating military and government institutions, rather than developing schools, organisations and businesses, which is what the movement must rely on today. The group’s survival likely depends on Gülen and his fellow leaders finding a way to change and admit their failings.

“They need that self-criticism, and then we can negotiate with them what went wrong and what will be their position in the political and social life of Turkey,” said Dündar. “But for the moment all I see is a total retreat and they don’t know what to do.”