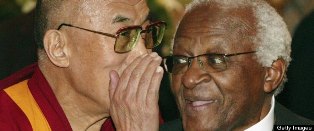

The Dalai Lama, wearing an orange visor, was on stage sitting next to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who had just flown in from South Africa. The Dalai Lama sat in his usual lotus position on a leather armchair that was a size too small for his folded legs. His knees stuck out a smidgen beyond the armrests.

“My main concern,” he said to Tutu, “what’s the best way to talk about deeper human values like love, compassion, forgiveness, these things. Not relying on God, but relying on ourselves.”

Tutu was hunched forward in his chair; he was carefully examining his hands, which were resting on his lap. He was dressed in a dark suit and a striking purple shirt with a decidedly magenta hue. A large metal cross hung below the clerical collar.

The Dalai Lama said, “I myself, I’m believer, I’m Buddhist monk. So for my own improvement, I utilize as much as I can Buddhist approach. But I never touch this when I talk with others. Buddhism is my business. Not business of other people. Frankly speaking”—he stole a glance at the archbishop and declared firmly—“when you and our brothers and sisters talk about God, creator, I’m nonbeliever.” He laughed, perhaps a little self-consciously.

It seemed to me that the Dalai Lama’s feelings about God have changed over the years. In an early interview, when I asked him if he thought there was a God, he answered simply, “I don’t know.” He took the view of an agnostic: he understood that it’s not possible to know one way or another whether God exists.

“In Buddhism no creator,” the Dalai Lama said at the Chan Centre. “But we also accept Buddha, bodhisattvas, these higher beings. However, if we only rely on these higher beings, we would just sit there, lazy.” He leaned into his chair, threw his head back, and rolled his eyes heavenward.

“Won’t help, won’t help. So that’s my view,” the Dalai Lama concluded

Tutu crossed his arms in front of his chest. He looked pensive, deep in thought. Then a smile creased his face. He said, “I was thinking when you were talking about God or no God, who you blame?” Tutu lifted both his legs from the floor and rocked back and forth in his chair. He was gripped in a fit of uncontrollable mirth. Perhaps it was an inside joke. If so, I didn’t get it. Perhaps he meant that if there is no God, then there is no one to blame but ourselves?

Tutu stared at the Dalai Lama as his trademark giggle filled the hall. The Dalai Lama then bowed deeply in homage, his head nearly level with his folded knees. He whipped off his visor and saluted his South African friend with an exaggerated flourish. Both men seemed to derive an enormous kick out of Tutu’s cryptic question.

Tutu said nothing more for the longest time. He was gathering his thoughts, preparing to expound further on the subject.

Although diminutive, all of five feet and four inches, his is an imposing figure. His facial features are broad and remarkably plastic.

Before Tutu could resume, the Dalai Lama pleaded, “I think . . . maybe I interfere. May I respond, just a little, just a little?”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” Tutu screeched in a loud, high-pitched voice that took the audience by surprise. He turned completely sideways and trained his eyes on the Dalai Lama, his face one of pure animation. The two elderly spiritual leaders, for one short, unforgettable moment, became kids again, horsing around and thoroughly enjoying each other’s company. At one gathering in Oslo, after a particularly rambunctious episode, Tutu admonished the Dalai Lama in mock seriousness, “Look here—the cameras are on you, stop behaving like a naughty schoolboy. Try to behave like a holy man.”

The audience at the sold-out Chan Centre was delighted with the bantering. It was heartening to see that these two global icons did not take themselves too seriously. That they could, without being the least bit self-conscious, display such childlike playfulness. The Dalai Lama was carried along by the archbishop’s animal vitality, his irreverence, his lighthearted theatrics.

He was so in synch with the African that he did something I have seldom seen him do before. He interrupted Tutu, with no regard for niceties or etiquette, in mid-thought.

But now that Tutu had given him permission to interrupt, the Dalai Lama turned serious. He said to the archbishop, “The problem is, if we involve religious faith, then there are many varieties and fundamental differences of views. So very complicated.

“That’s why in India”—he pointed a finger at Tutu for emphasis—“when they drafted the constitution they deliberately used secular approach. Too many religions there”—he counted them out one by one with his fingers—“Hindu, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, Sikhism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism. So many. And there are godly religions and there are godless religions. Who decides who is right?”

Now that the Dalai Lama had his say, he put his orange visor back on his bald pate.

Tutu replied, “Let me just say that one of the things we need to establish is that”—long pause—“God is not a Christian.” He paused again and turned to look at the Dalai Lama with a mischievous glint in his eyes. It had the intended effEct. The Tibetan leader laughed with abandon. Apparently, Tutu was not done with horsing around.

“Are you feeling better?” Tutu asked the Dalai Lama, who inclined his body far away from his friend and covered his eyes in mock surrender.

“We could go on, but . . .” Tutu turned thoughtful. He enunciated his words with great care, and paused for a long time after each phrase. He picked up the Dalai Lama’s earlier thread. “The glory about God is that God is a mystery. God is actually quite incredible in many ways. But God allows us to misunderstand her”—at this, the audience went wild; the applause was loud and spontaneous—“but also to understand her.”

“I’ve frequently said I’m glad I’m not God,” Tutu continued. “But I’m also glad God is God. He can watch us speak, spread hatred, in his name. Apartheid was for a long time justified by the church. We do the same when we say all those awful things we say about gays and lesbians. We speak on behalf of a God of love.

“The God that I worship is an omnipotent God,” Tutu intoned, opening his arms wide. He paused to let this sink in. Then he said, sotto voce, “He is also incredibly, totally impotent. The God that I worship is almighty, and also incredibly weak.

“He can sit there and watch me make a wrong choice. Now, if I was God,” he said as the hall burst into laughter, “and I saw, for instance, this one is going to make a choice that is going to destroy his family, I’d probably snuff him out.

“But the glory of God is actually mind-blowing. He can sit and not intervene because he has such an incredible, incredible reverence for my autonomy. He is prepared to let me go to hell. Freely. Rather than compel me to go to heaven.

“He weeps when he sees us do the things that we do to one another. But he does not send lightning bolts to destroy the ungodly. And that is fantastic. God says, ‘I can’t force you. I beg you, please for your own sake, make the right choice. I beg you.’

“When you do the right thing, God forgets about God’s divine dignity and he rushes and embraces you. ‘You came back, you came back. I love you. Oh how wonderful, you came back.’”

There was total silence in the hall. Tutu’s speech was a tour de force. The audience was captivated by his malleable facial features, which could change from fiery anger to deeply felt compassion in a heartbeat. His voice scaled multiple octaves. His arms and hands were in perpetual motion. He was a showman and preacher par excellence.

Later that day, Tutu and the Dalai Lama came together again in a small function room at the Chan Centre. They had another opportunity to expand on their views on religion before Tutu had to leave Vancouver.

“I think generally all religious traditions have good potential to improve human condition,” the Dalai Lama said to the archbishop. “However, some followers of religions, they are not very serious about one’s own teaching. They—out of selfishness, money, or power—use religion for personal gain. In some cases, because they completely isolated, so no idea about other traditions, value of other traditions. So that creates religious disharmony. But I think if you make balance, I think more weight to positive side than negative. Much, much more.”

“Yes, you are right,” Tutu replied. “And you have to remember that religion is of itself neither good nor bad. Christianity has produced the Ku Klux Klan. Christianity has produced those who killed doctors that perform abortions. Religion is a morally neutral thing. It is what you do with it. It is like a knife, a knife is good when you use it for cutting up bread for sandwiches. A knife is bad when you stick it in somebody’s gut. Religion is good when it produces a Dalai Lama, a Mother Teresa, a Martin Luther King.”

“And a Bishop Tutu,” the Dalai Lama interjected. Tutu stared at him, stuck a finger at his own chest, and admonished, “I’m talking!”

The Dalai Lama leaned back in playful recoil and laughed with abandon.

“But we’ve got to be very careful that we don’t say . . .” Tutu continued, ignoring him. But the Dalai Lama had trouble concentrating. His chest was heaving, his shoulders were jiggling with involuntary convulsions; he was having a hard time controlling his laugher. “Because there are bad Muslims, therefore Islam is a bad religion. Because there are bad Buddhists, Buddhism is bad. Just look at the Buddhist dictators in Burma,” Tutu said.

“We’ve got to say, what does your faith make you do? Make you become? I would not have survived without the faith of knowing that this is God’s world and that God is in charge, that evil is not going to prevail despite all appearance to the contrary. Yes, of course, sometimes, you want to whisper in God’s ear, ‘God, for goodness’ sake, we know that you are in charge, but why don’t you make this more obvious?’”

The Dalai Lama was not laughing any longer. He nodded vigorously as Tutu finished