By Desmond Lachman, Washington Examiner

Jan. 25, 2015 will be remembered as a watershed in the European economic crisis. On that day, Greece elected a radical, far-left government defiantly hostile to the current European policy of budget austerity and economic reform. The Greek electorate put the country on a collision course with its German paymaster that is almost certain to result in Greece being forced out of the euro before year-end.

It would be comforting if we, in the United States, could view Greece’s economic travails as occurring too far away to touch our economic welfare. Before indulging such wishful thinking, however, recall that a housing market collapse here in 2008, which at first was thought to be confined to a small part of the American economy, morphed into a global financial crisis that precipitated a deep worldwide recession. The European economy still accounts for a quarter of the world economy and is highly integrated with the global financial system. We cannot be complacent about fallout from the euro crisis.

Greece’s newfound defiance

It’s easy to see why the Greeks abandoned mainstream political parties and turned to a party on the far left. The country remains mired in an economic depression like the one the that afflicted the United States in the 1930s. Six years of recession have cut Greece’s economy by almost a quarter. Half its youth population is unemployed. The Greek middle class has been destroyed and the country’s social fabric has been torn asunder.

Humiliation at the hands of Greece’s creditors is stoking the fires of populism. In return for bailing Greece out for the past four years, its reviled “troika” of lenders — the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Economic Commission (EEC) — have forced Athens to accept extreme austerity. There have been draconian public spending cuts, big tax hikes, massive public sector job cuts, and pension payment reductions. The idea is to make the country more competitive within the euro straitjacket.

Throughout the election campaign, Alexis Tsipras, Greece’s youthful new prime minister, argued that the troika’s recipe had failed miserably both in Greece and throughout Europe’s economic periphery. He never tired of making the case that because the euro straitjacket prevents a country from devaluing its currency to boost exports and foreign investment, all the belt-tightening had proved counterproductive. Far from restoring Greek finances, austerity rendered the public debt even more clearly unsustainable.

The Greek government’s shaky start

Foreign observers hoped that, once in office, Mr. Tsipras would drop his electoral promises about confronting creditors. It was a false hope. If anything, Mr. Tsipras and Yanis Varoufakis, the flamboyant, leather-clad, tieless finance minister, have amplified their electoral rhetoric about the need for a new European economic model. They have won parliamentary backing for hardline negotiations with European partners for a new economic program for Greece when the current one expires in June.

On Feb. 8, 2015, in his first major address to the Greek parliament, Mr. Tsipras vowed to end budget austerity. He promised his government would raise the minimum wage, increase social spending, reverse public employment cuts, end property tax, and end the privatization of state assets. He did so knowing all his proposals would be anathema to the troika and to the German government in particular.

While pressing to end austerity, Athens also demands major debt relief and more money to tide it over for another six months while it dreams up a new economic policy. On a whirlwind tour of European capitols immediately following the Jan. 25 election, Mr. Varoufakis argued that Greece is simply not in a position to service its debt, which is now 175 percent the size of the entire economy. Rather than continuing the game of extending and pretending, Mr. Varoufakis has proposed a major write-down of Greek debt to a level it could afford to service.

Athens claims it has more leverage than its creditors in any negotiations. To the consternation of his Italian and Portuguese counterparts, Mr. Varoufakis points out that Italy and Portugal also have horribly weak public finances and citizens weary of austerity. Mr. Tsipras warns that if Greece abandoned the common currency, the whole euro project would unravel like a badly-knitted sweater.

Mr. Varoufakis also observes that if Greece is forced out of the euro, it would show plainly that membership is not irrevocable, and bank depositors in a eurozone country could lose their money. He repeated that a Greek exit could trigger bank runs in the rest of the eurozone. Mr. Varoufakis is plainly signaling to Berlin that Europe has much to lose by hanging tough against Greek demands.

A German brick wall

This has raised hackles in Berlin. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Wolfgang Schäuble, her finance minister, say Germany will not succumb to Greek blackmail. They note that if Greece wants to stay in the euro, it must honor its European commitments. And changes to Greece’s borrowing terms are to be made within the framework of Greece’s existing borrowing arrangements and no debt forgiveness will be countenanced.

Mr. Schäuble goes further, with his own diplomatic threat, saying Germany wants Greece to stay in the euro but won’t force it to do so. It’s up to Greece. If it keeps its European commitments it is welcome to stay. If it doesn’t, Germany won’t block the exits.

German constraints

Berlin is as constrained by domestic politics as Athens is. Germans are increasingly unsympathetic to the prospect of continually bailing out its impecunious southern neighbor. A recent poll showed that about half of all Germans now favor Greece leaving the euro. Mrs. Merkel also has to worry about the rise of a right wing Eurosceptic party, the Alternative for Germany, which has 10-12 percent support in state elections. Merkel cannot afford to be overly generous to Greece for it will weaken her right flank.

Merkel knows that any concessions to Greece could set a precedent for other European bankruptcies. If Greece gets a sweet deal, why not Ireland, Portugal and Spain? Such concessions could weaken incentives for debtor countries to abide by Europe’s rules. If there are rewards rather than penalties for breaking the rules, why would any country bother with austerity and reform?

Mrs. Merkel knows that the Greek negotiations are taking place against the backdrop of tremendous political change in Europe. Populist anti-European parties are on the march. In Spain, ahead of its year-end elections, the far-left Podemos party — its name is a translation of President Obama’s campaign slogan, “Yes We Can” — has risen from virtually nowhere and is now leading in the polls. In France, Marine Le Pen’s right wing National Front is France’s most popular political party. In Italy, all four political parties outside government favor leaving the euro. German generosity to Greece’s Syriza Party would be a gift for anti-euro forces in Europe who want to persuade their compatriots of the benefits of standing up to the Germans.

Bleak negotiating prospects

The constraints on Greek and German negotiating teams bode ill for achieving a durable new borrowing arrangement. The large differences between them relate not just to the thorny questions of debt relief and bridge financing, but also to what the appropriate size is for the Greek budget excluding interest payments. How is the Greek government to fund its ambitious social spending programs? How is it to make up for lost tax revenues? How will it get Greece’s structural economic reform back on track?

There is another cloud over the negotiations. It is the fact that German and European policymakers believe Europe could weather a Greek exit much more easily now than it could have during the meltdown of 2012. This is because most of Greece’s sovereign debt is now in official hands, not with privately-owned institutions. Default would not now pose a direct threat to the French and German banking systems. Since 2012, Europe has put financial firewalls in place that are meant to allow European policymakers to help other indebted countries on the European periphery from the fallout of a Greek withdrawal. They believe that this would insulate German and French banks. The firewalls include a well-funded European Stability Mechanism (ESM) which helps states in financial trouble, and the European Central Bank’s commitment to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

Europe’s Lehman moment?

But perhaps European policymakers are making a Lehman Brothers-type mistake by underestimating the risks of a Greek exit. In September 2008, American policymakers deciding what to do about Lehman’s acute financial difficulties grossly miscalculated the knock-on effects of letting the bank fail. They believed markets had used the six months since Bear Stearns’s rescue to anticipate the likelihood of a Lehman bankruptcy. With hindsight we know that the decision to let Lehman fail had devastating worldwide consequences.

A bank run following a Greek exit from the eurozone would tell depositors in the rest of the eurozone’s periphery that their deposits are not safe, neither recoverable nor backstopped by the ECB. Financial market contagion could spread from Greece to Italy, Portugal and Spain as depositors dash for their cash while it was still there.

Greek exit might also encourage political forces in core eurozone countries opposed to bailing out debtor nations. Greek financial and economic collapse would almost certainly trigger default on its 250 billion euro debt to the central bank, IMF and European Union. European policymakers could no longer maintain the fiction that lending to the European periphery was without high risk. All this will make future European bailouts difficult.

Policymakers might also be overestimating the strength of Europe’s financial safety nets. The European Stability Mechanism and an ECB that committed to buying many bonds to keep interest rates low are all very well, but they can only spring into action if the countries being supported commit themselves to IMF-style economic reforms — a questionable prospect.

Europe is a U.S. concern

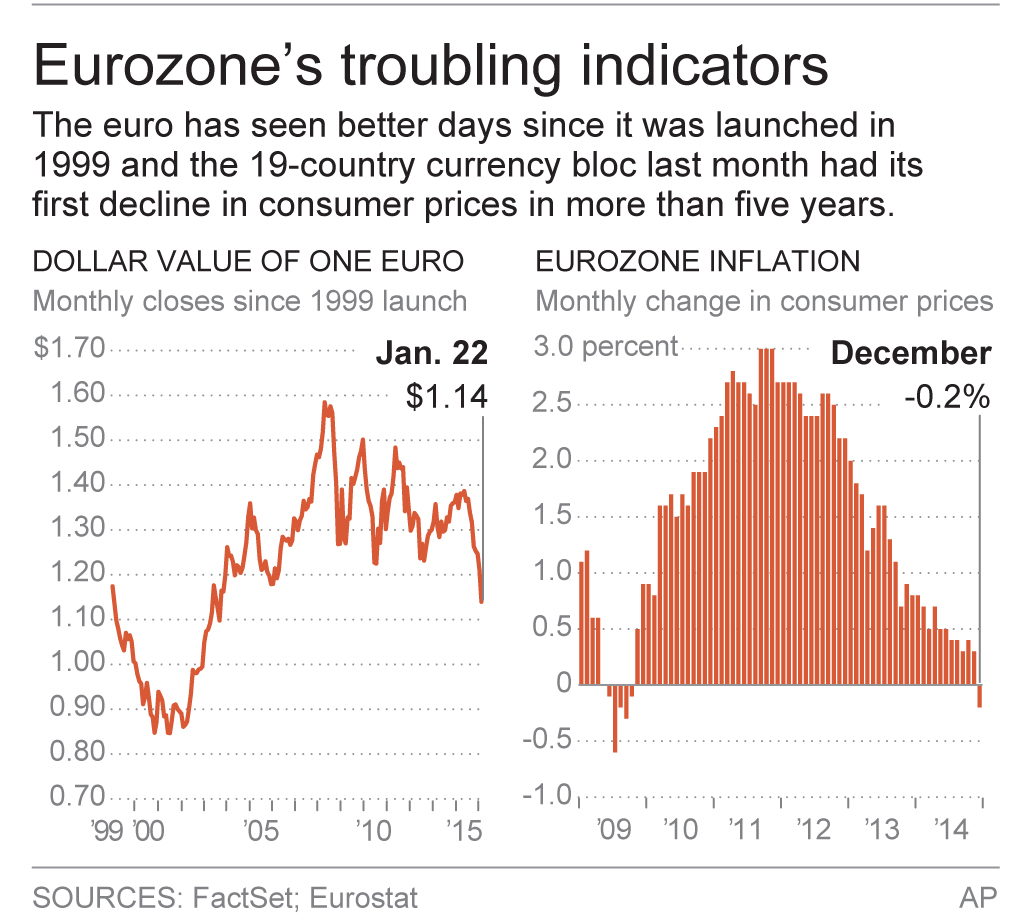

From an American perspective, Europe’s economic drama has to be of deep concern. This is not simply because the European economy is approximately the same size as that of the United States and because it would undermine growth globally if it stalled. Nor is it simply because crisis in the eurozone would further substantial strengthening in the dollar and undermine American business competitiveness. Rather, it is that the European banking system is highly integrated with the rest of the global financial system.

If there is just one lesson to be taken from the 2008 Lehman bankruptcy and the ensuing financial crisis, it is that everything is connected to everything else in the global financial system. Failure in one location ripples out to every other corner. The failure of one moderately-sized American investment bank produced a chain of events that brought the European banking system to its knees. So it’s impossible to ignore Greek flirtation with a break from the euro. It could bring defaults in Italy, Portugal and Spain.

From a U.S. policy perspective, two conclusions might be drawn. The first is that Washington should have every interest in preventing a Greek exit from the euro, and every effort should be made to help Athens and its European partners cut a deal. The second is that the Federal Reserve should not rush to start raising interest rates that might slow U.S. economic growth. If Greece is soon forced out of the euro, as appears to be a distinct possibility, growth here will face transatlantic headwinds.

Desmond Lachman is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a Deputy Director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.