by Ryan Mauro , FrontPage.

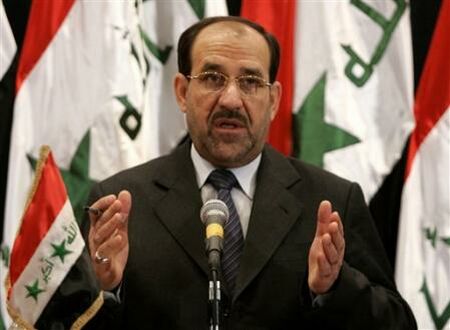

Iraq has steadily improved since the U.S. launched the "surge" of 2007. Security has increased, the economy has grown, democracy is taking hold, and cross-sectarian reconciliation is underway. All that could change, however, with the Iraqi government's decision, supported by Prime Minister Nouri Maliki, to ban 500 politicians for allegedly having ties to the outlawed Baath Party of the late Saddam Hussein.

On January 14, the Iraqi government's Independent High Election Commission sided with the Justice and Accountability Commission in its decision to ban over 500 politicians for allegedly having ties to the Baath Party. The earliest reporting said that these were nearly all Sunni politicians, indicating that the Shiite government was trying to minimize the strength of its sectarian rival ahead of the parliamentary elections on March 7, but Reuters received a copy of the list and found that two-thirds of those banned were Shiites. Many observers forget that, as Prime Minister Maliki has pointed out since the crisis began, 70 percent of the Baath Party membership was Shiite.

However, the effect is the greatest on the Sunnis, as some of their most prominent leaders have been kicked out of the political process without a public hearing. Among those banned are Defense Minister Abdulqadir al-Obeidi and Saleh al-Mutlaq, a Sunni leader who left the Baath Party in 1977 but has opposed the decision to ban the party. Mutlaq is far from a pro-American liberal. He has long demanded a U.S. withdrawal, courts Baath supporters, and has criticized America for branding "honorable national resistance movements" as terrorists. Still, Sunnis will interpret a ban on him as an act of Shiite-orchestrated oppression against them.

Furthermore, there is an obvious double standard here. As the Iraq the Model blog explains:

"While major existing partners in the political process are banned over alleged ties to the Ba'ath Party, the government is at the same time making deals with hostage killers like the group known as Asaib Ahl Al-Haq and is trying to persuade them to join the political process."

The ban is not necessarily sectarian in nature, but it is intended more to hurt the coalition of secular and religious Sunnis who have allied with former Prime Minister and secular Shiite Iyad Allawi to create a cross-sectarian, secular and anti-Iran political coalition that can challenge the ruling Shiite government and the more religious, pro-Iran parties. There were unconfirmed reports that this bloc was communicating with the Kurds about an alliance, which would make a decisive difference on election day.

Al-Maliki previously benefited politically when his Dawa Party ran on a non-sectarian, secular platform focused on security, and therefore is threatened by the ascent of a political bloc with similar credentials. Ahmed Chalabi, whose close ally is the head of the Justice and Accountability Commission, has thrown his lot in with the Iraqi National Coalition that includes pro-Iranian elements like the Sadrists and the Supreme Islamic Council. Al-Maliki originally formed his State of Law coalition to compete with this bloc, but has decided to ally with his former competitors following a meeting with Grand Ayatollah Al-Sistani.

To make matters worse, the Najaf province has reacted to a triple bombing by saying they are going to expel all residents with Baath ties and their families with very little notice for them to prepare. Current numbers are not available, but one report said that there were 130,000 Baathists in the province before Operation Iraqi Freedom began. Many Iraqis joined the Baath Party out of necessity, and relatively few fought to defend the overthrow of its rule. This extreme measure will almost certainly result in violence, and is seen in Iraq as an attempt to stifle secular and Sunni votes. Al-Maliki's Dawa Party surprisingly defeated the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council in Najaf during last year's provincial elections.

There is open talk of a Sunni boycott off the parliamentary elections, which would create a potentially insurmountable division between the sects. Should secular forces join in, then the division expands into political ideology. One Sunni politician who has been banned, Mustafa Kamal Shibeeb, is openly warning that "If there is no balance, there will be violence."

Neither violence nor a boycott will help the secularists or the Sunnis – or indeed anyone in the country wanting stability and progress. The correct approach would be for the banned politicians to turn it into political ammunition and encourage even greater turnout in order to prevent a monopoly on power in the hands of Al-Maliki and the pro-Iranian bloc he has formed an electoral alliance with. Unfortunately, the disenfranchisement of the Sunnis and the secular forces could lead to a disillusion with democracy and provoke strife that could quickly turn out of control.

Kenneth Pollack and Michael E. O'Hanlon warn that this "is just the kind of seemingly small problem that could unravel the entire political fabric of Iraq." Their statement came prior to the latest developments in Najaf. Iraq is about to face its biggest crisis since the astronomic levels of violence and near-civil war that preceded the surge. How the Iraqis handle it will have a profound impact on the West's security and the U.S. plan to finally withdraw its forces.