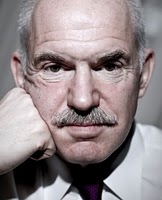

Guardian, Helen Smith

When George Papandreou, the Greek prime minister, swims, he cuts through the water with agility and speed. This week, the statuesque leader could be seen displaying Olympian stamina as he ploughed through the seas off the island of Poros. By contrast, Papandreou’s predecessor, Costas Karamanlis, preferred breast-stroke over crawl and more often than not the confines of a pool.

But, then, almost everything about the unmistakably fit, US-born Papandreou is different in manner and style of governance than Greeks are used to.As the politician who has led them through the country’s worst financial crisis in decades, his nine months in office have also been marked with more high drama than most as the governing socialists have tried not only to keep bankruptcy at bay but cope with a state now universally acknowledged to have failed those it was meant to serve.

“It has been crisis management, day in, day out,” he told the Guardian in his first major interview since Greece received €110bn (£92bn) of emergency international loans in May. “We knew that we had high debt and a high deficit with high inequality, high unemployment and negative growth … but we had no idea about the depth and breadth of the problems or the lack of good, transparent, democratic governance. When we found the deficit as high as it was [13.6% of GDP], we wanted to be absolutely transparent.”

Transparency is another hallmark of the 58-year-old son and grandson of former prime ministers, but in Papandreou’s case it has come at a cost – unprecedented austerity measures. It is a price that fellow progressive leaders, economists, academics and opinion makers, gathering in Poros to attend Papandreou’s annual international talk-shop, the Symi symposium, readily agree could still plunge Greece into social turmoil, poverty and despair.

For Papandreou there have been sleepless nights – even if he has displayed a rare coolness under pressure.

As the head of Socialist International, a global leftist network, he is not immune to the charge that, because of his government’s stringent public-sector cuts, the wrong people are now being made to pay for decades of profligacy, corruption, cronyism and tax evasion – chronic ills that have helped accrue a debt mountain in excess of €300bn, by far the EU’s largest.

In the last week, alone, the ruling Pasok party has passed legislation overhauling the pension system, shaking up labour laws and paring back benefits and allowances – rights that, unions say, have taken decades to win.

On Wednesday, it was the turn of policemen, firefighters and coast guard officials to take to the streets and protest against “barbarism”.

“Of course I feel very bad that we had to take these measures and that our financial sovereignty is under the tutelage of the so-called troika [the EU, International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank]. It’s not a happy state to be in,” said Papandreou.

“And the most painful thing is to take measures against people who were not responsible for the crisis … But you have to make tough decisions in politics. You can theorise about the options you have but in reality they are very specific. The option was: “Do we default or do we take these measures? Do we lose our pension system or do we save what we can? … it was a question of existence, of being able to pay civil servants their wages or losing that possibility”

Alone among Greek prime ministers, Papandreou has publicly declared that re-election is not his aim. If it means changing Greece “and mind-sets” for the better he will push through his modernising policies, whatever the political cost.

Already, he says, it feels like “a small revolution” as he has forged ahead with reforms, including new tax laws and a radical decentralisation plan, that no other prime minister has dared to enact in modern times. “My hope is that we will turn Greece into maybe the most transparent country in the world with everything on the web.”

Making the Greek economy more competitive by tackling corruption and bureaucracy are top priorities. So, too, is attracting badly needed foreign investment – and mobilising the younger generation to become a motor of change by setting up innovative start-ups and participating in grand schemes to “green” the economy by utilising Greece’s untapped potential through wind and solar energy.

The irony is not lost on Papandreou, or his aides, that much of this amounts to the dismantling of the state his father, Andreas, set up as Greece’s first elected socialist leader in the early 80s.

“I have always said I will be in politics to serve as best as I can and it will take me wherever it will take me,” says Papandreou.

“As long as I feel I am doing what I think is right and just for my country, for the Greek people, that is enough for me. Saving Greece from this crisis was the first thing on the agenda. We are now on a much more normalised road.”

But he also concedes that the path ahead is strewn with difficulties. After months of angry protests and bloody violence, culminating in the deaths of three bank employees in May, it is clear that the Greek people are not prepared to take austerity lying down.

For many, the recent respite is the lull before the storm – with worsening recession, galloping unemployment and mounting dissent within Papandreou’s own party looming on the horizon.

He accepts that in a nation where almost a quarter of the population lives under the poverty line, communication could be better.

In the months ahead, as measures really begin to bite, there will, he says, be greater urgency to “get out more into the neighbourhoods and countryside” to convey the message that Greeks must bite the bullet of austerity in return for seeing their country emerge reinvigorated out of the crisis.