By Nora Fisher Onar*, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Turkey is often touted as an inspiration for the rest of the Middle East—a characterization it accepts and pursues. In recent years, Turkish policy makers have worked hard to establish “Turkey Inc.”: a model of a relatively free, stable, and increasingly prosperous Muslim-majority country with great economic and foreign policy leverage. But what does the Turkish experience actually represent for the Arab Middle East? How convincing is Turkey, Inc.—and can it really be emulated?

Perhaps the most attention has been paid to the free and fair rise to power of its Justice and Development Party (AKP), which Islamist movements in Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and Syria have heralded as a symbol of Muslim majoritarian democracy—even explicitly referencing it in the names and platforms of their own parties, movements, and factions. To both domestic and international observers, this might signal that, like the AKP in Turkey, Islamist parties elsewhere do not seek to dismantle their states’ secular framework—at least for the time being.

But in spite of its appeal to both traditional Islamists and “post-Islamists”—that is, those who fully reconcile their particular politico-religious commitments with globalization—the Turkish formula may not be replicable. Civil-military relations in Turkey have undergone a double-sided transformation over recent decades. As a consequence of the army’s intermittent censure, political Islamists had to moderate their demands and practices; simultaneously, the army—accustomed to the barracks and aware that interference in government hurt Turkey’s international standing—increasingly relied on civilian allies to pursue its agenda vis-à-vis the AKP. Eventually, the military relinquished control of crucial institutions (like the National Security Council), and the final showdown over control of the presidency in 2007 was fought not with bullets and tanks, but with web declarations, public rallies, and court cases. A similar tipping point regarding civilian control of the state is hardly a foregone conclusion in countries still under transition where national militaries continue to exert a dominant presence in political life.

Other countries in the region also lack the trajectory of Turkey’s economic development—particularly, the export-driven rise of the middle class experienced by religious constituencies across the Anatolian periphery—something that has underpinned the AKP’s moderation, political success, and interregional presence. Indeed, Turkey’s recent economic trajectory is a central component to its appeal in the Arab world.

Over the past decade, Turkey has tripled its GDP and—excluding a dip to -4% real growth in 2009—has ridden out the global economic crisis with relative equanimity. Commentators have argued that Turkey may be part of a second tier of rising economic powers (alongside South Korea, Mexico, and Indonesia) hot on the heels of the Big Four (Brazil, Russia, India, and China). This holds two implications: on a symbolic level, the Turkish experience (along with that of Indonesia and Malaysia) has dramatically undermined theories of Islam’s incompatibility with modernization, especially in the arena of economic governance. More tangibly, over the past decade Turkey has actively sought partners for sustainable trade-driven growth in a region long addled by the heady cocktail of oil wealth and chronic underdevelopment. Although economic partnerships were in no way guided by concerns for democratic governance—attested to by Turkey’s once cozy ties with authoritarian leaders—they also have had unintended consequences with positive implications for political reform. For example, the influx of cheaper, better quality Turkish goods in Syrian markets may have undermined a backbone of the Assad regime: its business cronies.

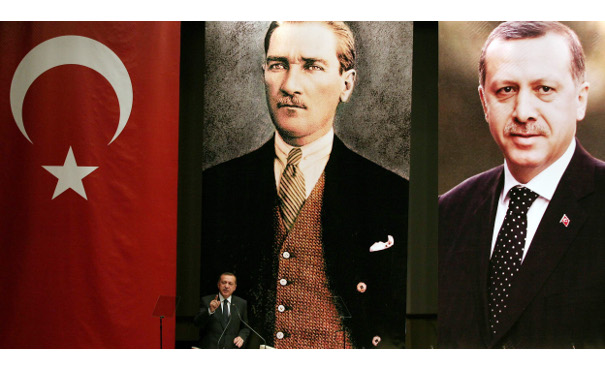

To understand the parameters of Turkey’s role in the region, we should also acknowledge the sensitivities that arise from the Ottoman legacy. Some believe that Ankara seeks to reclaim its historical leadership of the Middle East, the Caucasus, and the Balkans, something that can rub interlocutors the wrong way. Hence, Turkish foreign policy makers’ reluctance to employ Ottomanist frames of reference. But at the domestic social level, there remains a growing receptiveness to self-depiction as the benign heir to the Ottoman Empire. This is evident in the proliferation of cultural commodities that employ Ottoman referents, such as the recent record-grossing film Conquest 1453 about what western historiography calls the “fall” of Constantinople. In the film, Mehmet the Conqueror—played by an actor who bears a remarkable resemblance to a young Recep Tayyip Erdogan—is shown to be a forceful and compassionate protector of Muslims and Christians alike (though there is no mention of Jews). The image of Turkey as a “big brother” to downtrodden Muslims in places like Palestine, Nagorno-Karabagh, Kosovo, and Bosnia—characterizes an emerging “neo-Ottomanist” national image that seems to drive Turkish aspirations of regional leadership within the country and amplify Erdoğan’s profile abroad. Whether this is a matter of hubris or of capacity remains to be seen.

A final component that is crucial for evaluating Turkey’s example is that the country has yet to develop a framework for meaningful multi-ethnic, multi-sectarian co-habitation. Mounting violence on the part of militant Kurds and the state’s heavy-handed response fuels hostility between ordinary citizens. Recent court rulings suggest that vigilante terror towards prominent members of the Armenian and Alevi communities is permissible and will go unpunished. Disturbing numbers of journalists, scholars, and students who express critical views on these fronts are jailed. There is also deep concern in constituencies which embrace secular lifestyles that recent reforms in fields like education will yield an ever more restricted society. Given the need to put its own house in order and the fact that inter-communal tensions across the region are likely to become worse before becoming better, Turkey’s AKP must take very seriously its mandate to write a new and inclusive constitution. In the longer tem, Turkey must confront the standing challenge of the region—learning to live together despite differences—a challenge which is also Turkey’s own.

At the end of the day, the export of Turkey Inc. needs stable and predictable conditions in which trade and investment can thrive; hence, the commitment to the “zero problems” policy that Turkey employed with neighbors in its economic and foreign agendas over the past decade. Due to last year’s upheavals, however, this policy is unsustainable. Once well-placed to broker a dialogue between Iran and Israel, Turkey is now alienated from both as the two nemeses lock horns in what Graham Allison has called the “Cuban missile crisis in slow motion.” Should this spill into war, the delicate balance in Iraq may unravel into protracted sectarian and ethnic conflict, just as Syria’s brewing civil war may spill over into Lebanon. But even without an Israeli-Iranian showdown and an intensified conflagration in Iraq and Syria, the country’s Kurdish question is, quite literally, kindling awaiting a flame, as attested to by recent clashes during Nevruz/Newroz celebrations. All of this suggests that Turkey’s aspirations to regional leadership are tactically dependent on forestalling an Iranian-Israeli showdown—an end to which it should leverage all its diminished diplomatic capital in the two countries and in partnership with the United States.

Before the AKP and Arab Awakening, the received wisdom was that when it came to Islam, democracy, and secularism, one could have any two but never all three. Similarly, doubts have long been expressed as to whether political and economic liberalism can thrive simultaneously in a Muslim-majority setting. Taken together, it seems that if the purveyors of Turkey Inc. can show that liberal economics goes hand-in-hand with liberal democracy in a country governed by pious Muslims, the Turkish model-in-progress may achieve fruition and offer a timely example for the region.

Nora Fisher Onar is an assistant professor of International Relations at Bahçeşehir University in Istanbul. She is a Ronald D. Asmus Policy Entrepreneur Fellow with the German Marshall Fund and is a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for International Studies (CIS) at the University of Oxford.