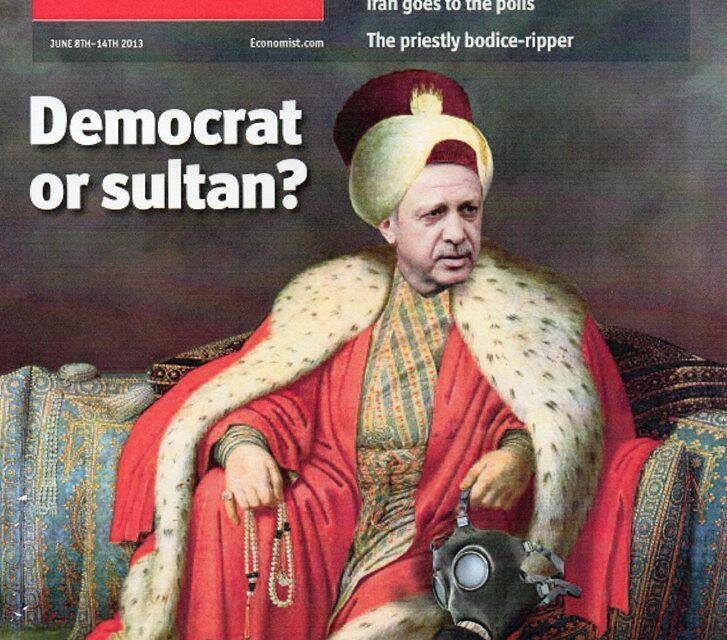

The Economist

BROKEN heads, tear gas, water-cannon: it must be Cairo, Tripoli or some other capital of a brutal dictatorship. Yet this is not Tahrir but Taksim Square, in Istanbul, Europe’s biggest city and the business capital of democratic Turkey. The protests are a sign of rising dissatisfaction with Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s most important leader since Ataturk. The rioting spread like wildfire across the country. Over 4,000 people have been hurt and over 900 were arrested; three have died.

The spark of protest was a plan to redevelop Gezi Park, one of the last green spots in central Istanbul. Resentment has been smouldering over the government’s big construction projects, ranging from a third bridge over the Bosporus to a crazy canal from the Black Sea. But only after this first protest was met by horribly heavy-handed policing did the blaze spread, via Twitter and other social media. A local dispute turned national because its elements—brutal police behaviour and mega-projects rammed through with a dismissive lack of consultation—serve as an extreme example of the authoritarian way Mr Erdogan now runs his country (see article).

For some observers, Turkey’s upheaval provides new evidence that Islam and democracy cannot coexist. But Mr Erdogan’s religiosity is beside the point. The real lesson of these events is about authoritarianism: Turkey will not put up with a middle-class democrat behaving like an Ottoman sultan.

Alighting from the democratic train

In some ways, Mr Erdogan has done well. GDP growth has averaged over 5% a year since his Justice and Development (AK) party took office in late 2002. The government also pushed through enough reforms to earn the start of membership talks with the European Union in 2005, a prize that had eluded Turkey for 40 years. Mr Erdogan has done more than any of his predecessors to settle matters with his country’s 15m repressed and restless Kurds. Turkey has come to be seen as a model for nations emerging from the Arab spring.

This record explains why AK has won three commanding electoral victories, the most recent in June 2011. Mr Erdogan remains popular, especially among small-business owners and the conservative Anatolian peasantry who make up most of the millions of recent migrants to the cities. Against a useless opposition, AK may well win again.

Yet there have long been worries about Mr Erdogan. He once called democracy a train from which you get off once you reach the station. He is disdainful of the cosmopolitan bourgeoisie of Istanbul and Izmir. His party’s religious roots led many to fear the Islamisation of Ataturk’s proudly secular state: a new law restricting alcohol sales lent credence to those worries. Some fret that, far from being a model of Islamist democracy, AK might expose the concept as an oxymoron.

Yet there are many in Mr Erdogan’s party who, like its co-founder, Turkey’s president, Abdullah Gul, disapprove of the prime minister’s authoritarianism and find his interpretation of democracy too narrow; and there are many non-Muslim leaders, such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Hungary’s Viktor Orban (see article), who behave high-handedly. The problem is not Islam but Mr Erdogan. He has a majoritarian notion of politics: if he wins an election, he believes he is entitled to do what he likes until the next one. Sometimes, as in defanging the coup-prone army, he has used power well. But over time the checks on him have fallen away. AK nominees fill the judiciary and AK people run the provinces; their friends win the big contracts. Mr Erdogan has intimidated the media into self-censorship: as the protesters choked on tear gas, the television networks carried programmes about cooking and penguins.

More journalists are in jail in Turkey than in China. Mr Erdogan has locked up whole staff-colleges of generals. Within his own party, people are afraid to stand up to him. His self-belief long ago swelled into rank intolerance. His social conservatism has warped into social engineering.

The risk is that he will now hold onto power even more tightly. Under AK party rules that limit deputies to three terms in the parliament, he must stand down as prime minister at the next election in 2015. He may be tempted to change the constitution so that he can become a powerful executive president, or run his party from the presidential palace, or simply change the rules so that he can stay on.

Ottomans are to be sat on, nowadays

For two reasons Mr Erdogan must abandon these ideas and prepare to pass leadership of AK, and executive power, to the more statesmanlike Mr Gul at the next election. One is that many Turks are tiring of him—just as poll-tax riots in 1990 signalled that Britons had tired of Margaret Thatcher, or the French rejected Charles de Gaulle after 1968. If Mr Erdogan stays, he may find his country increasingly ungovernable.

He also needs to preserve his achievements, which are already fragile and are at risk of unravelling. The economy has slowed sharply, partly because of recession in the euro zone, Turkey’s biggest market. Talks with the EU have ground to a halt and Mr Erdogan seems to have lost interest. Negotiations with the Kurds, particularly with Abdullah Ocalan, the jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, are on a knife-edge.

Mr Erdogan could use the promise of an orderly succession to set Turkey on the right course. The country needs a new constitution to replace the 1982 one drafted by the army; but it should be done by consensus among all parties and it should devolve rather than centralise power. Were Mr Erdogan to devote his remaining time to constitutional reform, to finding a settlement with the Kurds and to using revived EU talks to keep democracy and the economy on track, his place in Turkish history would be secure.

This week’s protests have not been all tear gas and streaming eyes. Ordinary people in ordinary districts have been banging pots and pans and hanging out flags to make their voices heard. Many Turks have found a new sense of unity that in time could foster genuine, pluralistic democracy—if only the sultan would listen. Much is riding on how he treats the protesters in Taksim Square.