By WILLIAM R. RHODES, The New York Times

The euro zone’s political leaders and senior European Commission officials have drifted off for their summer vacations, apparently confident that the European Central Bank will guard against August surprises and hopeful that September’s German general elections will be followed by a wave of German generosity that will restore the region’s economic stability. The perspective from New York is one of rising disbelief in the complacency of those most responsible for the euro zone’s course.

The International Monetary Fund’s latest report on euro-zone conditions should be a wake-up call. It describes the root causes of pervasive weakness in growth as “persistent financial market fragmentation, weak bank balance sheets, low demand, and creeping uncertainty as well as structural weaknesses, all reinforce each other and contribute to contraction of real activity.”

While the president of the E.C.B., Mario Draghi, recently suggested that there were some signs of economic improvement in the euro zone, he, like the International Monetary Fund, admitted that the downside risks were substantial, as indeed they are. The I.M.F. sees euro zone G.D.P. declining for a second year in 2013 by 0.6 percent and then recovering modestly next year with growth of 0.9 percent.

Forecasts for the zone as a whole mask grave situations in some of the most troubled economies. In a new report on Spain, for example, the I.M.F. said that despite substantial economic reforms the jobless rate was unlikely to fall significantly in coming years and could well stand at 25 percent in 2018.

For many months now the euro zone’s authorities have failed to finalize critical features of an urgently needed banking union. Meanwhile, banks are striving to boost capital by deleveraging and selling assets. Small and medium-sized enterprises in many countries, which are the engines of employment, are starved of credit. The prospects in the countries on the periphery of a reduction in today’s record-level unemployment are bleak. These countries face a lost decade of economic progress that will trap tens of millions of people in misery.

Reviving growth requires investment, but investors’ confidence is almost certainly going to decline further. Not only is there no evidence of strengthening competitiveness in some of the hardest-hit countries on the periphery, several of the countries in the euro zone that were doing well are finding that attaining growth is increasingly difficult. Sluggish growth in many other parts of the world is compounding the export prospects of the euro zone countries as well.

Crucially important for investor sentiment is a sense that national leaders in the euro zone are finding ways to revive public confidence in their ability to restore stability and pursue a path to growth. The opposite is now the case. Despite the fact that some of the zone’s leaders are basking in the summer sunshine, the combination of all the unsettling daily political news from Rome, Madrid, Dublin, Athens, Lisbon and Paris is as bad as at any time since Greece’s budget malfeasance was revealed in December 2009 and the crisis started.

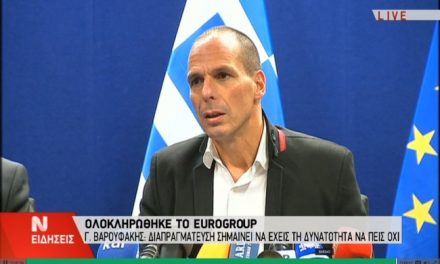

The disarray at the top of the government in Portugal has raised doubts about the country’s ability to follow through with economic policies that for a time looked as if they were on the right course. Allegations of secret party slush funds and payoffs to top politicians in Spain could undermine essential banking and budgetary reforms. The weak Italian coalition government could fall at any moment because of an array of political challenges. In Ireland, the public airing of taped conversations between bankers and officials at the height of the financial crisis is taking public confidence in government to new lows. In Greece, a former finance minister has been charged with corruption, strikes are mounting, the government is finding it very difficult to implement its privatization program and essential structural reforms.

The euro zone’s authorities have repeatedly underestimated the risks of crisis. They promoted austerity measures without recognizing the degree to which this would compound unemployment. They ignored warnings of likely contagion in early 2010, at a time when they should have moved fast to negotiate a debt restructuring, which wasn’t achieved until 2012. Now a further Greek debt restructuring is essential, but again euro zone officials are unwilling to consider this in a timely manner.

Corporate investors look at the full array of economic and political factors in the euro zone as they determine whether to make the job-creating investments that so many euro zone countries need. On almost every count, at least seen from this side of the Atlantic, economic conditions appear to be deteriorating. At some point this will become widely recognized across all segments of finance, and the E.C.B. will discover that just pumping in liquidity will not suffice to prevent economic conditions from getting worse.

Instead of vacationing, the euro zone’s leaders and key officials should be working together around the clock to set agreements to improve supervision of the financial system through a robust banking union; they should strengthen the mechanisms they have put in place to provide essential credit to countries in trouble; and they should revive serious thinking about a fiscal pact that commits all governments to budget stability. Just as importantly, they need to set firm timelines for implementing action on each of these core policies. The longer they wait, the tougher the problems will become and the greater will be the risk of serious shocks to the system.

William R. Rhodes, former senior vice chairman of Citigroup, is president and C.E.O. of William R. Rhodes Global Advisors, and the author of “Banker to the World: Leadership Lessons from the Front Lines of Global Finance.”