Some days ago a friend who was reading Ryszard Kapuściński’s “Travels with Herodotus” wrote me with an inspiring paragraph from the book: “A journey, after all, neither begins in the instant we set out, nor ends when we have reached our doorstep once again. It starts much earlier and is really never over, because the film of memory continues running on inside of us long after we have come to a physical standstill.”

Indeed, a journey stays with us a long time, and it continually shapes us.

It is then that I decided that instead of writing about the global problems tormenting us during the past months, I will write about my personal journeys — because they are still very much with me. I will talk about returning to two places that I feel a close attachment to: the Greek island of Crete, and the U.S. state of Texas. I have a special relationship with both places. Greece is where I traveled for the first time by myself, a coming-of-age journey, a place where I formed family-like bonds, and where I try to go at least once a year. I went to the United States because of my job, and I developed friendships that I feel grateful for. It is therefore hard to write in an impersonal way and describe the dynamics of the two, but I will try explaining why both destinations stay with me in assessing what’s going on in the world — in my world.

Ten years ago, I was flying to Crete, an island in the Eastern Mediterranean, to become a student at an institute on international relations that was gathering young people from the Mediterranean region and Eastern Europe. This year, I had the privilege to return and lecture at the institute – the International Academy for Advanced Studies. My emotions as I started lecturing are difficult to describe. Most of the talks one has in Chania are related, in one way or another, to the fate of the world. At least this is what I have experienced. Maybe because of its location — in the middle of the sea and almost as close to Africa as it is to Greece. Much of that dynamic, though, was due to the company of talented people with whom one can better understand how the “love of one’s own” can spur discussions that make cooperation between peoples seem so easy to accomplish. During the talks, both inside and outside the classroom, you start to realize that personal roots not only define the way we are, but also the way peoples in the world act in relation to each other — insight that is useful in the attempt to predict what will happen next. As George Friedman says: “The search for predictability suffuses all of the human condition.”

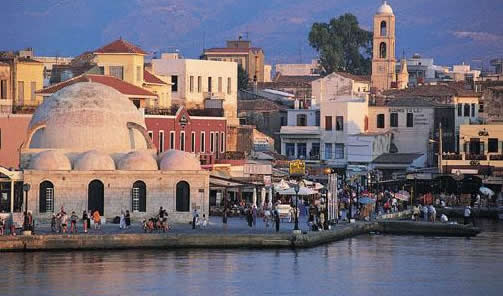

Philosophical discussions are definitely not new to Chania, considering its rich heritage. Born as ancient Kydonia in 3000 B.C., the city now called Chania lived through the Arab occupation (823-961), the Byzantine period (961-1252), the Venetian occupation (1252-1645), the Turkish occupation (1645-1897), the independent state of Crete from 1989 to 1913, when it became a capital, until finally became the largest island in Greece. Because of its history and location, which makes it a borderland of all civilizations in the Mediterranean, Crete has become a place where the West meets the East and the North meets the sunny South. The ancient port, with its old lighthouse, its mosque, and the ruins of a 17th-century church, brings you back in time — you ponder the troublesome history that the island has lived throughout the centuries. Day and night, the main cities on the island (and Chania in particular) gather merchants from the Mediterranean, each giving a different flavor to the place.

A landscape marked by pinkish oleanders and the scent of lavender blended with the sun-scorched agitation of Chania’s downtown, just as it did 10 years ago, as I went for a walk through the city. Strolling along the main street, I found the shop where I used to buy pistachios, the coffee shop where I had my first fredo on the island, and even the shop where I bought my leather wallet. The shopkeepers worked with the same frenetic energy today as I remembered them doing in the past, and the opening hours of the shops outside the touristy downtown district were just as unclear as they had been before. That made me realize that the crisis didn’t hit Crete. The island economy has managed to adjust itself, and while the food is cheaper relative to other places in Europe, the flow of tourists hasn’t diminished, but increased.

The economic development that took place on the island during the years before the crisis is visible. You can see the results of investment in infrastructure. Archeological sites that have received EU funding are prettier and more accessible. However, the real estate business has clearly stagnated during the last couple of years. Driving on the island, you see more houses that are deserted, in bad shape or left unfinished are than you would have seen 10 years ago.

Despite the signs of crisis, Crete’s quality of life doesn’t seem to have been substantially altered. The priority is living whatever life offers to the full, and smiling most of the time. A good conversation about the world, about a book, about good food can always create an environment that allows people to forget about everyday troubles, which are many. But the quality of life here was never reduced to economic success and has always gone beyond, with friendship and hospitality the main expression of the free Greek spirit in the Mediterranean.

The detachment of Greeks, the jokes about “who governs Greece,” the pleasure of holding discussions over coffee for long hours in the afternoon or even at night, the breeze of the Mediterranean, these things seduce everyone and make you forget all theories about efficiency and time pressure.

What stands out when you visit Texas, and especially its capital, Austin, is the way it has grown over the last few years, becoming a hub for businesses and attracting human resources. Everywhere you look in the downtown area, you will see a crane. Seven years ago I was amazed at how you would run into an empty plot of land while walking in the downtown area – now, an empty spot is hard to find. Apartments buildings have been built to accommodate the newcomers that the town attracts, from businessmen to college students. What has stayed the same are the main attractions: the trail and the Sixth Street. The trail by the Colorado River is the place where locals go to jog. Europeans visitors such as myself, on the other hand, use the benches along the trail to read by the river, or just walk around admiring the natural surroundings and the beautiful sunsets of Texas. This is why, to me, the trail is most beautiful during evenings. Sixth Street is where you go to socialize, and unlike in Greece, long discussions over a cup of coffee are not common at all here. The coffee is replaced with alcoholic beverages, and socializing takes place after working hours — mostly on Fridays and weekend nights. The coffee shops’ daytime clients would usually work on their laptops and do not talk much outside of the screens they are staring into. In the suburbs, life begins at 5 p.m., when families gather and start preparing dinner or doing housework. Everything is organized and well scheduled. Everyone seems to have a well-defined role in society.

What stands out when you visit Texas, and especially its capital, Austin, is the way it has grown over the last few years, becoming a hub for businesses and attracting human resources. Everywhere you look in the downtown area, you will see a crane. Seven years ago I was amazed at how you would run into an empty plot of land while walking in the downtown area – now, an empty spot is hard to find. Apartments buildings have been built to accommodate the newcomers that the town attracts, from businessmen to college students. What has stayed the same are the main attractions: the trail and the Sixth Street. The trail by the Colorado River is the place where locals go to jog. Europeans visitors such as myself, on the other hand, use the benches along the trail to read by the river, or just walk around admiring the natural surroundings and the beautiful sunsets of Texas. This is why, to me, the trail is most beautiful during evenings. Sixth Street is where you go to socialize, and unlike in Greece, long discussions over a cup of coffee are not common at all here. The coffee is replaced with alcoholic beverages, and socializing takes place after working hours — mostly on Fridays and weekend nights. The coffee shops’ daytime clients would usually work on their laptops and do not talk much outside of the screens they are staring into. In the suburbs, life begins at 5 p.m., when families gather and start preparing dinner or doing housework. Everything is organized and well scheduled. Everyone seems to have a well-defined role in society.

On a road trip to nearby Fredericksburg, I was told that Germans settled in the Hill Country south of Austin. Driving through Texas is relaxing, not only because the road is large enough for you to feel safe, but also because the sky seems to be nearer. Unlike driving through European countryside, you will not see houses or farms — you’ll mostly see the fences ringing rural plots, and sometimes the entrances to farms and ranches. That speaks a lot to the culture of Texas as well: The large plots of land offer the peace of mind that comes with privacy. Something that for a European equates to isolation, for the American is the perfect way of living – and if you ask how the police might protect residents in these areas, they would answer that there’s a gun in most houses ready at all times, but that in any event the crime rate is minimal.

Also due to large spaces, the community of villages is replaced in Texas with the community of shared values that sometimes relate to religious-based communities. The church plays an important role in people’s lives, providing a gathering place for those who share similar values. While religion is an important factor in politics and setting up communities, demography is another important element in understanding Texas. Latinos are the second-largest group in Texas after non-Hispanic European Americans. In downtown Austin, you mostly run into the descendants of European, but in time, you will discover that the city is far more diverse, a reality reflected, for instance, in the city’s cuisine. Mere miles south, San Antonio presents a completely different kind of city. Latinos are the majority. The food is tastier – and spicier – and the architecture is clearly influenced by neighboring Mexico.

The Texas that I’ve grown to know is very much like a multitude of colored patches that never mix together, yet coexist and develop in the same geography. The patches are formed of different cultures and communities, all of them bound by clear societal rules meant to develop the place they live in by subordinating themselves to the economic law of efficiency.

When I arrived in the United States for the first time, I was told that American society is still in the making, still discovering and struggling with itself, while European society is a civilization: a settled culture, a settled way of life that has had its fights and moved past them. I don’t like generalizations, and while I admit that the American society that I have come to know does indeed fight with itself, it is the same energy created through these struggles that makes the country capable of fostering so much talent and innovation. I believe that Europe still has its own fights to carry out, and hopefully, these will lead to new talent and innovation, allowing us to discover a new and better (even if not necessarily entirely settled) Europe.