By ROBERT D. McFADDEN, The New York Times

Glafkos Clerides, the president of Cyprus from 1993 to 2003, who as leader of his nation’s Greek Cypriot majority was a frustrated peacemaker in futile talks with Turkish Cypriots to reunify their long-divided Mediterranean island, died on Friday in Nicosia, the capital. He was 94.

His death was confirmed by Yianna Shiatou, the press attaché at the Cyprus Consulate in New York.

In a land torn by ethnic, religious and cultural rivalries, tugged by Turkey to the north and Greece to the west, Mr. Clerides (pronounced cleh-REE-dess) was a national leader for more than four decades after independence from Britain in 1960. World statesmen and both sides in the Cypriot tinderbox regarded him as a fair, skillful negotiator, seeking compromises for the elusive goal of reunification.

Mr. Clerides had been a World War II hero, a lawyer and fighter in the anti-British resistance, and an ally of Archbishop Makarios, primate of the Cypriot Orthodox Church and first president of the Republic of Cyprus. He also headed a Greek Cypriot delegation that helped write a new Constitution, was the leader of Parliament for 16 years and won two terms as president.

As Cyprus faced a succession of crises — a Greek-inspired coup, an invasion by Turkey, a 1974 partition into unequal zones, years of intercommunal fighting — Mr. Clerides negotiated cease-fires, accepted international peacekeeping buffers and sought to pacify militants with concessions, offering to cede territory and even to rewrite the Constitution in search of peaceful solutions.

In talks with Rauf Denktash, a Turkish Cypriot leader who had been his friend since childhood and his negotiating opponent for 25 years, Mr. Clerides — a voice of calm in a nation known for volcanic orators — won some tactical agreements, and came close to a breakthrough in their last reunification talks, in 2002.

But he was ultimately stymied by forces beyond his control: by allies and foes fearful of giving away too much, by governments in Athens and Ankara with their own agendas, and by walls of distrust between Greek and Turkish Cypriots that had taken generations to erect.

After losing his 2003 re-election bid, Mr. Clerides supported a plan by Kofi Annan, the United Nations secretary general, to reunify Cyprus and allow hundreds of thousands who had been displaced by partition to return to their homes. Turkish Cypriots, hoping to end their isolation, supported the plan overwhelmingly in a 2004 referendum. But Greek Cypriots, the vast majority of the population, soundly defeated it.

While reunification eluded Mr. Clerides, as it has all Cypriot leaders, he was credited as president with easing sectarian tensions, presiding over a prospering economy and leading Cyprus to the threshold of European Union membership, a process that he began in 1998 and that was achieved in 2004.

Mr. Clerides was the author of a four-volume memoir, “My Deposition” (1988-91), which he called “the anatomy of a national tragedy.” Mr. Denktash, his fraternal negotiating rival, who died in 2012, often quoted from it, saying it was a scrupulous record of events.

Glafkos John Clerides was born in Nicosia on April 24, 1919, the son of John and Elli Clerides. His father was a teacher who became a London lawyer. Glafkos grew up under British colonialism. Cyprus, settled by Greeks and conquered by Alexander, the Persians and the Ottoman Empire, had been placed under British rule in 1878, annexed in 1914 and made a colony in 1925.

Glafkos, like his father, went to London to study law. But when World War II began in 1939, he joined the Royal Air Force and flew bombing missions as a tail gunner. His plane was shot down in a 1942 raid on Hamburg, and he was captured by the Germans. He escaped three times from prison camps, but was recaptured each time. After the war, he was cited for distinguished service.

In 1945 he married Lilla Erulkar, an actress born in what was then Bombay who took the name Lilla Irene Clerides. She died in 2007. The couple had a daughter, Katherine, who survives him. She became a member of Parliament and a leader of his Democratic Rally Party.

Mr. Clerides resumed law studies at King’s College London, graduated in 1948 and returned to Cyprus to practice. As Britain rejected postwar calls for self-determination, Greek and Turkish Cypriots in 1955 formed separate resistance groups with divergent goals and plunged into four years of guerrilla war against the British and each other, aiming less at independence than at unions with their motherlands.

Mr. Clerides joined the Greek EOKA resistance, defending its fighters in courts by day and planning strikes with them by night, using the nom de guerre Ypereides, after an ancient Athenian orator. He accompanied Archbishop Makarios to London in 1959 for talks that led to a cease-fire and independence, and became minister of justice in the transition.

In 1960 he was elected speaker of the House of Representatives and became Nicosia’s chief negotiator in the conflict between Greek Christians, who with 80 percent of the island’s 750,000 people occupied the southern two-thirds of Cyprus, and the mainly Muslim Turks in the north, protected by Turkey 50 miles offshore. Intercommunal fighting in 1963 led to military intervention by the United Nations.

In 1974 Athens briefly deposed Archbishop Makarios, Turkey invaded Cyprus and United Nations peacekeepers partitioned the island. About 230,000 people were resettled. In the turmoil of shattered communities and threatened civil war, Mr. Clerides became acting president for five months until Archbishop Makarios returned.

It was only a bitter taste of the office he would occupy two decades later. He lost presidential races in 1983 and 1988, then narrowly won in 1993. (He was also a candidate in the 1978 election, but when his rival’s son was kidnapped, Mr. Clerides withdrew in a gesture of sympathy.)

His rapport with Mr. Denktash raised hopes that he might succeed where his predecessors had failed to unite Cyprus, but their 1996 talks crumbled. He was re-elected in 1998, but his last hope for reunification during his term faltered in the 2002 talks.

After losing the 2003 election, Mr. Clerides retired to Larnaca, on the southeast coast. His life and the history of modern Cyprus were re-examined in “Glafkos Clerides: The Path of a Country” (2008), by Niyazi Kizilyurek, a Turkish Cypriot professor.

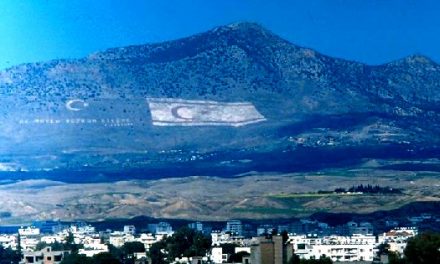

Cyprus is still divided. The Turkish side favors a two-nation state in loose federation, while the Greek Cypriot government wants a unified state that grants fair distribution of social and political rights to both communities.