Financial Times

For much of the post-cold war era, the EU's role in international affairs has been something resembling a Japan of the west.

An economic and trading power, it has tried to shape world events through foreign aid, tariff concessions and the occasional carefully crafted sanctions regime. It has tamed its own backyard through membership of the EU club, but such measures have had a marginal impact on the global order.

Like its east Asian counterpart, the EU has been an afterthought in high-end geopolitics, forced to be content with a few photo opportunities at G7 summits. When anything significant happened, Brussels would issue a strongly worded demarche and the big decisions would revert to London and Paris. If things got really bad, there was also that handsome relic of a US-led alliance out by the airport, Nato HQ.

But suddenly, and literally overnight, the Russian occupation of Crimea seems to have awakened Europe's mandarins to the fact that the EU can be a first-tier player in international events. If Russia views the EU as a strategic threat, the least we can do, Europe's own diplomats are suddenly saying, is view the EU in the same way.

"Just imagining this could have been done as a humdrum technocratic exercise like the EU does everything else, it shouldn't have been a surprise you couldn't do that," laments one veteran Brussels-based diplomat of the EU's approach to Ukraine before the crisis. "You can't take all the politics out of politics."

Officials in the EU's capital involved in closed-door deliberations since the Russian takeover of Crimea say there are still signs of narrow, diffuse short-termism on the part of several member states. But increasingly, the big powers have argued for strong, collective action in the interest of a long-term goal – even at the expense of short-term pain at home. This is the very definition of strategic thinking.

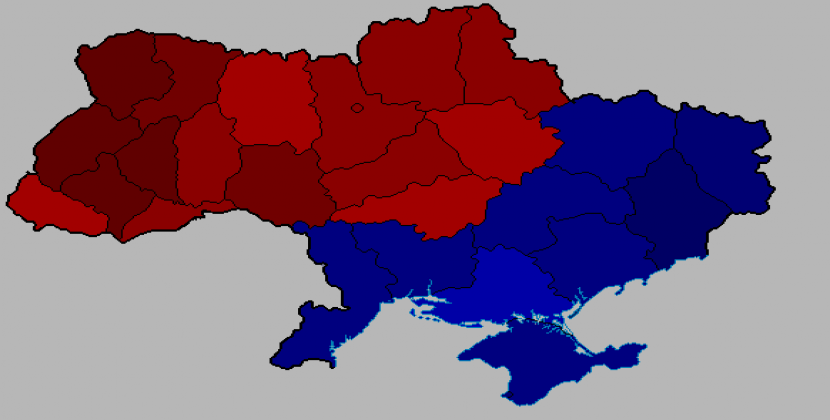

The tabular content relating to this article is not available to view. Apologies in advance for the inconvenience caused.

>"They normally don't think together at all and then when they think together it's short-term," says Jan Techau, a former German defence ministry official who has been a lonely voice for a "strategic Europe" since setting up a Brussels branch of the Carnegie Endowment think-tank four years ago. "They're now thinking together long-term. If this doesn't wake us up, nothing will wake us up."

The key player in this awakening, as it always is in the EU, has been Germany. For much of the post-unification era, Berlin's relationship with the Kremlin has been transactional, based on its deep and broad bilateral energy and business relationships. Eastern Europeans still fume at Germany's decision a decade ago to back a Russian pipeline through the Baltic sea, delivering Russian gas to German shores by bypassing its eastern neighbours.

But 10 days ago, after nearly daily calls with Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, German Chancellor Angela Merkel backed an unexpectedly strong move towards sanctions at an emergency EU summit. German mercantile interests were subsumed to the collective goal of upholding the postwar international system. The first targets of those sanctions are expected to be chosen by foreign ministers on Monday.

<>The current spate of strategic thinking could be a temporary case of the vapours. The EU's recent record has been less than encouraging. Brussels largely sleepwalked through the Arab spring despite repeated protestations that it was seriously revamping its approach to its southern neighbours.

But the kind of long-term strategy that could help north Africa – particularly opening up EU markets to southern Mediterranean agriculture and textiles so the region's economies can grow, politics stabilise and migrants stop attempts to cross on sink-prone vessels – has been stymied by short-term protectionism.

Similarly, the past 18 months has provided unseemly scenes of Ms Merkel, France's Francois Hollande and Britain's David Cameron making back-to-back-to-back pilgrimages to Beijing to hawk their countries' wares despite widespread allegations of Chinese commercial dumping in Europe and Sino-Japanese brinkmanship in the East China Sea.

But Jean Monnet, the French statesman credited as the EU's founding father, once said Europe would only be "forged in crises". It was a truism too often favourably cited during the eurozone conflagration, when such forging also threw millions out of work. But perhaps it may prove a more promising outcome in Ukraine.