By Alen Mattich, Wall Street Journal

Greek assets may be looking slightly more perky today, but Thursday’s sharp losses ought to be a worry for investors with exposure to Italy and Spain.

Greek government three year bonds took another beating, with yields rising above 10%–they were snapped up at under 3.5% when issued in July. But perhaps that shouldn’t be surprising. Investors are worried–with reason–they could find an anti-austerity government prepared to default on the country’s debt in power within the next couple of months.

Greek equities also suffered hefty losses, with Greek banks leading the falls. And that too makes sense in light of how closely linked finance firms have been shown to be since the first rumblings of the financial crisis in 2007.

But if Greek investors were running scared, there’s no reason for complacency anywhere across the eurozone’s southern fringes.

For one thing, Italian sovereign debt levels are just as menacing as Greece’s, even if yields remain near historic lows. But most worrying is the even bigger dependence of Italy’s banking sector on the government bonds.

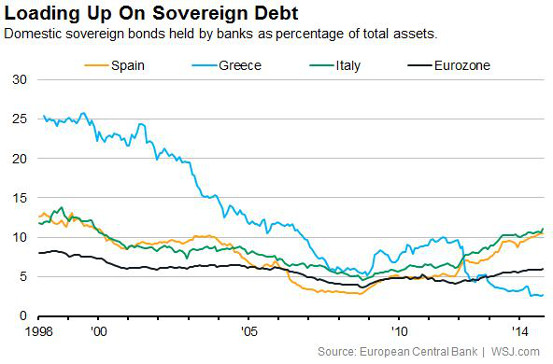

The latest data show that Italian banks hold more than 11% of their assets in Italian government debt, the highest proportion since the late 1990s. By contrast, Greek banks have steadily been trimming their exposure to the sovereign since the worst of the eurozone crisis–from 10% in the summer of 2011 to 2.7% now.

Nor are Italy’s banks alone. Spanish banks have also been increasing their holdings of domestic sovereign debt, doubling over the past three years to 10.5% now.

This especially matters because Italian and Spanish government debt has been bid up to record levels (sending yields to record lows). At these sort of valuations, it wouldn’t take a lot of bad news from Greece to once again raise the prospect of member countries abandoning the euro–or being ejected. This so-called convertibility risk would force up risk premia, as it did during the worst of the eurozone crisis and lead to a significant sell-off of sovereign debt across the region’s periphery.

Any significant drop in Italian and Spanish bonds–thus a rise in their yields–would quickly raise concerns about their banks’ capital adequacy. And that’s how vicious cycles start.

Weak banks then make people worry that they might have to be bailed out by sovereigns. But already high sovereign debt loads then increase prospects of sovereign default. It doesn’t take many iterations of this cycle for sovereign yields to rocket and banks shares to collapse.

This isn’t to say Italy or Spain will slip into one of these vicious cycles. Or even that this is any more than a very low probability risk. But to judge by Spanish and Italian bond yields, investors seem to be betting there’s no chance the deadly pas a deux between Europe’s sovereigns and banks will start up again.