The European Central Bank told the newly elected Syriza anti-austerity government to address the country’s economic illness with urgent surgery and stop searching abroad for a miracle cure.

The ECB said it would no longer accept Greek bonds as collateral for monetary operations from next Wednesday. This means that Greek banks cannot use their bonds for cash funding from other banks, but they will have to ask the Greek central bank for liquidity.

This move is both technical and political and not a complete disavowal of the new Greek team. In fact, it removes the potential risk of Greek bonds from the books of European banks to those of the European central bank system to avoid that the weakest European banks would be tempted by possibly relatively high Greek interest rates or deep discounts to fill their coffers with potentially risky paper.

However, the Greek government is now under pressure to come up with a realistic and sound economic recovery plan in order to obtain the debt restructuring it desperately needs.

In Greece, several banks had been tapping their central bank for emergency funding as worried customers took their money away. This liquidity issue could be solved by the Greek banks by turning to other European banks with their debt as collateral. These banks would then go to the ECB and use it to get fresh funds.

That would have introduced a rotten apple in the cash system – the most sensitive part of the banking system, open to wild swings that can get multiplied through other market segments, starting with the currency markets. There the ECB said “Stop”.

The real Greek problem is about its debt and overdue economic reforms.

Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras won a landslide election victory on his promise to renegotiate the terms to a joint bail-out of the country by the ECB, European Union and IMF.

That bail-out, in the heat of the government-debt crisis, saved Greece and the euro and added extra hardship on the already suffering Greek people in an economy sapped by tax evasion, corruption, nepotism and megalomaniac projects such as the Athens Olympic Games.

Wages and pensions fell, consumption dropped, small businesses are having payment problems and state services do not function. The rich moved to their villas, some poor and young sought a better future abroad, in Britain, Germany or the United States. Others stayed put, short of money and robbed of a future.

Tsipras won because his new party did not bear any guilt to the legacy situation – in contrast to the socialist and centre-right parties – and because he promised to renegotiate and cut the debt burden.

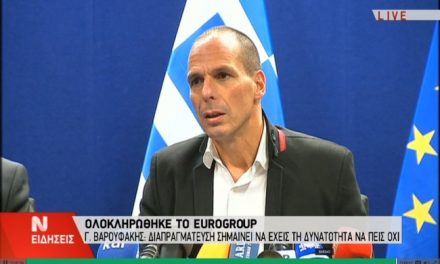

Tsipras and his finance minister Yanis Varoufakis are on a whirlwind tour of European capitals, not wearing ties or snappy suits as a kind of new hair shirt, to get backing for their plans.

The Greek government cannot alleviate the plight of its citizens and voters if it does not have room to spend. Its budget is eaten up by debt service costs – interest rates and reimbursements – so it can only lighten up on austerity measures if it can reduce the debt bill.

Yes and No

The anti-austerity message went down well in other quarters, such as in Italy and France who are engaged in a drawn-out arm wrestling match with EU paymaster Germany. They want to go soft on austerity so that governments can boost their stagnant economies with demand side measures.

Germany says “Nein” and wants to keep the strict budget deficit rules.

ECB president Mario Draghi announced the qualitative easing program of more than a trillion euros with the majority backing of his council but against the wish of Germany.

He did that partly because Germany was stopping European states from engaging on supportive measures for their economies, something that Draghi had long prompted them to do.

Germany has urged Europe to be firm on Greece, with no concessions. European parliament president Martin Schulz, a German social democrat and no internal Merkel ally, said Greece risked national bankruptcy.

Draghi, while the ECB is independent, could not permit to lose more credibility currency with Germany by not siding with them on this Greek issue.

That is the political reason behind the ECB stance.

That is also the reason why French president François Hollande told Tsipras that while debt talks should continue and while he was working on changing Europe’s economic policies, the Greek needed to adhere to the EU rules. Hollande cannot afford to displease Chancellor Angela Merkel on this point either, as he needs all his personal credit with her for other issues.

And now?

Meanwhile Varoufakis has changed his tone a bit and is no longer suggesting debt cuts but talking about new maturities, new growth bonds and other technical solutions that could lighten the debt burden without reneging on debt commitments.

He will have to negotiate with the other European countries, banks and the IMF about the debt package. Those are unlikely to give in an inch as long as there is no clarity on the new government’s policies to deal with the Greek economy.

They cannot give in because it would be unfair to other countries that have been bailed-out (Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Cyprus) and create a precedent for whoever would come next.

Tsipras cannot just forget his election promises, as some German leaders have suggested.

But he will have to tell the Greek that while he is doing what he can – and his European tour is a clear indication to the Greek voters that he is working hard – he cannot just wave a magic wand to solve the problems.

The new government’s domestic economy plans are not clear. It has stopped several privatization programs in the first cabinet meeting but Tsipras will have to look closely at how to sell state assets at the best possible way.

The government will need to relentlessly hunt tax evaders, especially the big fish, stamp out corruption and abandon the privileges of several interest groups.

The Greek orthodox church is wealthy and owns a lot of property in the country that is hardly taxed. The church also provides social serves the state can no longer afford.

Rich shipowners hold their assets outside Greece.

The Greek army counts 85,000 people (rising to 250,000 in war time due to reservists). That is down from more than 90,000 just a few years back but compares with 115,000 for France, 91,000 for the United Kingdom (without reserves) and 60,000 for Germany. Italy has 105,000 people under arms.

There are 18 Greek billionaires, and six Greek American billionaires. Three are on the Forbes top-500 with a combined $6 billion earned in banking, refining, shipping and real estate.

The government can help small businesses by cutting red tape, setting steep penalties on late payments, banning all-inclusive holiday packages so that tourists spend in the streets of the Greek villages and towns and not just in tourism complex. It can promote on-the-job learning to get people suited for jobs, it can create a social service next to military service for young adults to work in care to the elderly and ill – reducing youth unemployment and providing a state service that can otherwise hardly be funded.

It also needs to attack monopolies and other anti-competitive practices.

But above all, the new government will have to show that it is serious about structural reforms, tax collection and asset sales. Only then can it expect to get concessions on its debt maturity schedule and possible debt-swaps.