Marcus Bensasson, Bloomberg

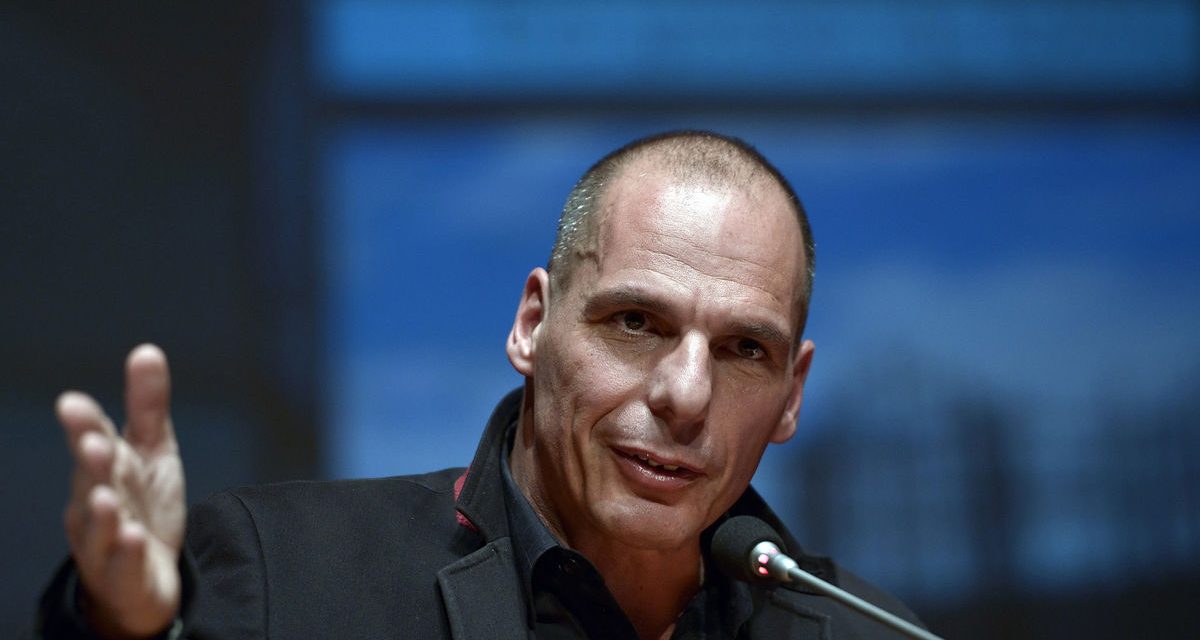

The root of Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis’s desperation for debt relief will be laid bare in the coming days.

The backdrop for the new government is an economy lumbered with near-record unemployment and a deflationary spiral after the country plunged into its worst slump since World War II. While data on Friday may confirm the economy grew in each quarter of 2014, it has a long way to go to regain output lost in six years of recession, with the current political crunch threatening to trip up the recovery.

Since coming to power in an election last month, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has maintained his pledge to help Greeks by reversing the austerity imposed under the country’s bailout. That’s led to clashes with other European governments before a leaders summit in Brussels on Thursday, sent stocks spinning and raised the risk of the country abandoning the single currency.

Greece’s statistics office will publish unemployment data for November later on Thursday. That’s forecast to come in a 25.7 percent, according to a Bloomberg survey of economists, more than twice the euro-area average.

The gross-domestic-product data may show the economy grew 0.4 percent in the three months through December. The European Commission estimates GDP rose 1 percent in 2014, which would be the first full-year expansion since 2007. Economic contractions since then have left GDP 26 percent below its pre-crisis peak, with household disposable incomes falling by a similar amount.

Varoufakis gathered with euro-area counterparts in Brussels late Wednesday for an emergency meeting about Greece’s request for a temporary financial accord to gain time for negotiations on its debt. He spent much of last week traveling Europe, holding one-on-one talks with finance ministers in France, Germany, and the U.K. to try to win support.

Tsipras will meet his German counterpart for the first time at a European Union summit on Thursday. Chancellor Angela Merkel, the biggest contributor to Greece’s financial rescue, sees little room for maneuver on support for Greece, with French President Francois Hollande and Italian Premier Matteo Renzi having signaled willingness to conciliate.

Watering Down

In the face of opposition, the Greek government has already watered down its position on the debt, ditching a pre-election pledge for a write down in its nominal value. Greece has more than 320 billion euros ($362 billion) in debt outstanding, about 175 percent of GDP, mostly in the form of bailout loans from the euro area and the International Monetary Fund.

Frustration over the unsurmountable pile of debt — even after the world’s biggest-ever restructuring in 2012 — and the dismal economic state helped Tsipras and his anti-austerity Syriza party topple former Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’s New Democracy in last month’s elections. Tsipras lined out a range of measures in a policy speech on Sunday including pledges to increase the minimum wage and halt the privatization of infrastructure.

Greece’s benchmark ASE Index has dropped 5.6 percent since the vote on Jan. 25. The three-year note yield has doubled in the same period to 20.8 percent.

Political Standoff

Greek consumer prices plunged an annual 2.5 percent in December and the decline probably accelerated last month. The European Commission forecasts that prices will fall an average 0.3 percent in 2015, a third year of declines.

A 3.8 percent drop in industrial production in December may in part reflect uncertainty related to the political standoff over a new president, which prompted the election, according to James Nixon, chief European economist at Oxford Economics Ltd. in London.

“If a deal can be struck, in many ways a lot of the things Syriza is proposing should actually be quite positive for consumption,” he said. “The concerns about the Syriza program are really in the longer term. Unemployment is a quarter of the workforce and you’re looking at a decade-long process to get it down and get the economy back to where it was in 2007.”