by Simeon Djankov, Peterson Institute

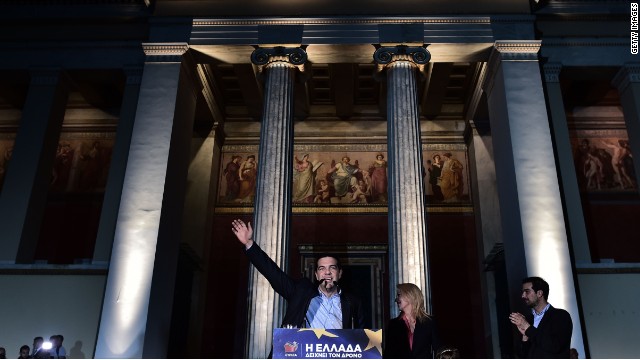

Less than a month after taking power, the Greek government led by Syriza finds itself in a difficult place. This is due to the grand miscalculation of its leaders that Europe will blink in front of the victory that its leader, Alexis Tsipras, achieved in last month’s elections. Quite the opposite: So far Europe has called Syriza’s bluff, leaving it with little room to maneuver.

While its coalition is a relatively new formation, Syriza is no newcomer to Greek politics. Tsipras has been in politics for 20 years, starting as a member of the Youth Communists in the 1990s and entering the municipal council of Athens in 2006. The finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, was economic advisor in 2004 to former prime minister Georgios Papandreou. How could a team that is not a novice miscalculate so badly the chances of succeeding with their anti-austerity program?

Opposition politicians often promise more than they can deliver while trying to unseat an incumbent government. But the populist agenda usually stops soon after the new government is formed. Not this time. The vitriol against the German-led fiscal responsibility drive in Europe has continued.

The miscalculation lies in Syriza underestimating the insistence of Southern European countries, which have undergone their own austerity measures, that Greece not be permitted to ease up on its austerity program. Were the future of Greece the only issue in question, the euro area might have been a more willing listener. But with elections in Portugal and Spain in September and December of this year, respectively, the euro area has a lot to lose from yielding to Greece’s populism. In particular, the Spanish counterpart to Syriza—Podemos—is watching carefully how the debate in Brussels and Athens develops.

And while leftist populists are currently riding high across Europe, the biggest challenge to the euro area’s stability may come from the populist right—from Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France. With presidential elections in two years, the National Front enjoys unparalleled approval, and Le Pen may well be a serious contender for the presidency. The National Front’s economic program is remarkably similar to Syriza’s: rolling back fiscal responsibility and increasing state intervention in the economy.

Regardless of how Syriza’s negotiations with the euro area end up, the recent populist drive in Europe has already contributed something positive to the growth discussion in Brussels: the investment plan of Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission. The plan marshals €315 billion to spend on new roads, ports, energy facilities, green technology, and information technology projects. Many of these were planned in national budgets or private initiatives but cancelled or delayed as a result of the euro area crisis. Jyrki Katainen, European Commission Vice-President for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness, is tasked with making Juncker’s plan operational by the summer. In my experience as finance minister of Bulgaria, working alongside Katainen during the euro area crisis, he is the right person for the job.

Perhaps a happy compromise can be found after all: that a large share of projects under Juncker’s investment plan take place in Southern Europe. Such a plan would help growth in these countries and reduce the inequality in job opportunities between North and South, which has become the new dividing line in Europe.