A few years ago, the Berkeley Police Department applied for and received a grant from the state of California to improve the behavior of local drivers.

The grant came on the heels of data showing that Berkeley was perhaps the most dangerous city in the state in which to cross the street: The previous year more pedestrians had been struck by automobiles in Berkeley than in any of the 55 other comparably sized California cities.

But as anyone who lives here knows, the drivers aren’t really the problem. Or rather, they aren’t any more of a problem than they are any place else in California, and probably a lot less of one.

The Berkeley pedestrian, on the other hand, seems bent on his own destruction. In daylight hours you can find him sprinting from behind tall bushes into busy intersections, ear buds in place to ensure he remains oblivious to any danger; at night he dons dark clothing and slips, ninja-like, from shadows onto poorly lit streets. It’s California law that a pedestrian, when he arrives at a crosswalk, must stop and make eye contact with any approaching driver: Hardly anyone here pays that law any attention. If the Berkeley pedestrian glances up at all, it’s to glare at any driver moving slowly enough to notice his sudden, almost magical appearance in the middle of the road.

Behind that glare lies the source of the peculiar danger on Berkeley’s streets. The Berkeley pedestrian is propelled not just by his desire to get from one place to another but also by his sense that he’s doing it in a morally superior way. He believes — even if he might not quite put it this way — that it is the duty of all fossil-fuel consuming, global-warming promoting, morally inferior users of the road to suffer on his behalf. He’s not suicidal. He doesn’t want to be run over by a car. He simply wants to stress to you, and perhaps even himself, that he occupies the high ground. In doing so, he happens to increase the likelihood that he will wind up in the back of an ambulance.

Which brings me to the current dispute between the Greeks and the Germans.

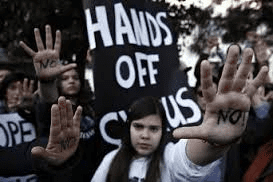

In the new Greek finance minister’s (pretty great) macho bluster, in the new Greek prime minister’s condescending lectures to the German people, in the unquenchable Greek thirst for magazine cartoons of German leaders in Nazi uniforms — in all of it you see the soul of the Berkeley pedestrian. It’s only the source of Greek self-righteousness that is obviously different: The Greek people think the German people should feel shame for the sins of their past, and an obligation to expiate those sins.

As if to illustrate the point, the Greek Ministry of Finance recently commissioned a study to determine how much Germany should payGreece for the atrocities committed by Germans in World War II. (The number they came up with, 301 billion euros, was suspiciously close to Greece’s outstanding debt.) This study did not make it more likely that Germany would pay Greece reparations: just the reverse. It enraged the German politicians whose indulgence the Greek government now seeks. But it still served its purpose — to remind everyone that the Greek people still insist on their own righteousness.

Greek government corruption, cheating on taxes, resistance to reform: Never mind all that! If a Greek wants to sprint across the autobahn, every German still has an obligation to notice and hit the brakes.

Everywhere you turn in Greece you now see that ordinary feelings of self-preservation have been suspended. The willingness of the Greeks to vote into power a party bent on antagonizing their creditors is the most obvious example, but there are others. For instance, every week comes some report of Greek people pulling a few billions of euros out of their banks, presumably to move it to safer banks based in Germany and Switzerland. That isn’t surprising; what’s shocking is that there are still savings to withdraw from Greek banks.

Every Greek now knows there is a very real possibility that Greece will leave the euro. If that happens, the euros in Greek bank accounts will become, overnight, new drachmas, and be worth perhaps half of what they were valued the day before. The risk is real and easily avoided — and yet there are, by last count, 140 billion or so euros ($160 billion) still on deposit with these Greek banks — earning roughly 1.5 percent annual interest. If Greece were to exit the euro zone tomorrow, roughly 70 billion euros of Greek savings that might have been preserved with a phone call, would go poof.

It’s possible that these Greek savers know something the rest of the world doesn’t. It’s possible that they are too lazy or fatalistic to bother to prepare for the worst. But I’ll bet a lot of those euros still held in Greek banks are governed by the spirit that governs the behavior of the Berkeley pedestrian. It’s an “I dare you to do this to me” sentiment, hardened perhaps by five years of repetition.

If you want to predict what people will do in most financial situations, then figure out what is in their narrow self-interest to do, and assume they will sooner or later figure it out, too. But that doesn’t work when people’s behavior isn’t confined to the narrow channel of self-interest. That’s why it’s so hard to predict which way the Greek people will jump. And why it must feel so tempting, when they jump right in front of your BMW, to simply run them over.