The Greek finance minister’s portrayal in the media relies on facile national stereotypes

Yanis Varoufakis may or may not end up saving Greece’s economy — but he’s certainly giving the media a lot to gossip about.

At a meeting in Riga, Latvia, with his European counterparts, Varoufakis, the Greek finance minister was reportedly “savaged” and later labeled a “gambler” and an “amateur” by an unnamed source in Bloomberg. This report was then repeated in most of the European press. The Greek negotiating team was subsequently reshaped, with alternate minster Eyclid Tsakalotos taking the helm of the Brussels team and technocrat George Chouliarakis tackling the day-to-day technical level negotiations.

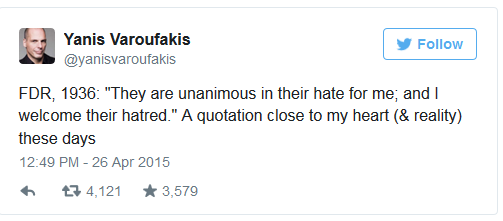

Varoufakis, it seemed, was on his way out, and he appeared to acknowledge his new marginal position. Channeling Franklin Delano Roosevelt, he tweeted a few weeks ago:

Only his sidelining now seems to have been purely for appearances’ sake. Two weeks after sending his beleaguered tweet, he was back in Brussels. And Varoufakis denies that the insults in Riga ever took place. Financial Times journalist Peter Spiegel felt the need on May 21, after almost a month, to say that no one attacked Varoufakis in the meeting. But this small detail was distorted by stories in Business Insider, The Guardian and The Telegraph.

“The media went into a frenzy of obfuscations and lies, which I am sure they are not entirely responsible for,” Varoufakis told The New York Times in a profile published this week. “All these reports that I was abused, that I was called names, that I was called a time waster and all that — let me say that I deny this with every fiber of my body.”

This denial and the somewhat late clarifications, call into question the reliability of the outlets that examine his every move and reproduce often distorting, one-sided statements by anonymous sources. Can we trust the information coming out of Brussels? And why is this one man, once propped up as a European revolutionary, getting so viciously torn down?

The media’s treatment of Varoufakis is a symbol of how they, and the European Union, have approached the Greek question since the crisis began. An anonymous, ill-informed and one-sided opinion claiming the Greek positions are unrealistic is given more merit than an entire country’s demand for an end to austerity. Like Varoufakis in this case, a stereotype of the Greek national character is put before facts and figures.

Shooting the messenger

The problem, from the start, was the cult of personality that the media built up around the him and the symbolism it carried. The Varoufakis narrative isn’t about one man; it’s a stand-in for an entire nation.

While his intellectual credentials and the honesty of his positions are hard to deny — he has stuck by his views since the beginning of the Greek crisis and published books and dozens of articles in support of his analysis — what got him the attention of the international media was his disdain for convention, with his leather jacket, shaved head and motorbike. When he visited the U.K. to meet Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, the Brits loved him. (Londoners did, after all, elect the markedly more outrageous Boris Johnson as their mayor.) There was hardly any international outlet that didn’t carry a profile or an interview of his since Syriza won in the elections in January. “Rebel,” “rock star” and “erratic Marxist” (which he chose for himself) were just a few of the labels following him around. But the technocrats in Brussels were less impressed.

This is what also made him the ideal scapegoat, onto which journalists and their readers could project their ambivalence (and perhaps lack of understanding) about the entire eurozone crisis.

Varoufakis went to Brussels in January with a very simple mandate: to renegotiate Greece’s bailout deals, which had brought little more to the country other than a deep recession and what the country’s leaders repeatedly refer to as a humanitarian crisis. Even if he wanted to, he couldn’t capitulate to the demands of the country’s lenders and continue with the austerity program. He has been clear about his dim view of the austerity regime, calling it tantamount to leaving the euro, but he doesn’t believe a Grexit is a good move, nor does the Greek electorate that voted for him.

However, his reasonable (and decidedly nonradical) position never ended up being the focus of the talks or the coverage thereof.

For example, when the Greeks ask why the country should privatize profit by selling public assets, such as regional airports, the only answer available to them in Brussels is “Because you have to.” When Syriza officials suggest other ways out of the slump, the only reply available seems to them be “You can’t do that, because we say so,” regardless of the plethora of evidence that suggests the Greek economy can’t handle more cuts and recessionary measures.

Instead of taking his ideas seriously, Varoufakis’ European counterparts obsessed over his clothes and his manners — perhaps to avoid the hard work of restructuring Greece’s unviable debt and backing down on measures that, on the basis of how they have worked over the past five years, will sink the country further into recession.

Similarly, when Syriza brought up the issue of war reparations that Germany might owe Greece, it was almost universally shunned.

Pale and tired

As the media picked apart Varoufakis, from his smirk to his casual footwear, ugly stereotypes about Greeks resurfaced. In a German daily, the reporter wrote that while “the other finance ministers looked pale and tired, Varoufakis looked as if he had just come back from vacation.” The fallacy of hardworking northerners and lazy southerners should have been put to rest with the 20th century but is still around in 2015.

The press briefings cited in most media — which come almost exclusively from unofficial, anonymous sources — said that the discussions that took place over the past few months were no better. They spoke of Greece having no viable proposals and of living in an alternative reality. They accused Varoufakis of being an ideologue, as though German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s notion of “expansionary contraction,” which was used to justify the austerity dogma, wasn’t in and of itself an ideological intervention (let alone a contradiction in terms). They even complained that Varoufakis was lecturing them on macroeconomics.

He was, in a way. “One of the great ironies of the Eurogroup is that there is no macroeconomic discussion. It’s all rules based, as if the rules are God given and as if the rules can go against the rules of macroeconomics,” Varoufakis said in The Irish Times, in response to a criticism by Ireland’s finance minister that he was “too theoretical.”

For now, Varoufakis, like Greece, enjoys too much unwanted attention. While support for Syriza is growing and the party is now leading with 21 percentage points over New Democracy, everyone from everyday supporters of the party (as recent polls have shown) to Greek businesses agrees that the negotiations have gone on too long.

But it’s also becoming obvious that when close to a solution, the EU goes back to the table with demands that make no sense in the current context. Earlier this week The Wall Street Journal reported that German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble “showed no willingness to compromise in the negotiations to unlock the final installment of Greece’s 245 billion euro ($272 billion) bailout.” And in late-night talks on Thursday, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras met with his counterparts from France and Germany; the atmosphere, Bloomberg reported, was convivial, but the team failed to reach an agreement to release additional bailout funds.

We’re running out of time, as we’re only a few weeks before Greece is forced to default on billions of euros in debt repayments. Europe and the international media should stop talking about its finance minister’s clothes and address his nation’s needs and the ideas that he is putting on the table.

Yiannis Baboulias is a journalist, writer and founding member of Precarious Europe. His work has been featured in The London Review of Books, The New Statesman, Vice, Open Democracy and The Guardian, among others.