by: SINAN ÜLGEN & MARC PIERINI, Carnagie Europe

On June 7, Turkey’s electorate shook up the country’s political landscape: the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost its parliamentary majority, while the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) entered the legislature for the first time. In this blog post, Sinan Ülgen assesses the domestic implications of the result, then Marc Pierini considers Turkey’s international outlook.

After almost thirteen years of single-party government, Turkey is entering an era of coalitions. No party was able to obtain a clear majority at the parliamentary election on June 7. With almost all the votes counted, the ruling AKP looks to have won 258 seats, eighteen short of a majority. This result was a setback for the party’s ambition to establish another single-party government.

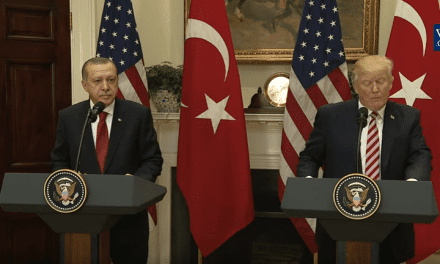

However, the outcome was an even bigger setback for President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s plans to change Turkey’s constitution and introduce an executive presidency. Although the election failed to settle the uncertainty over the nature of the next government, it firmly put to rest the question of an executive presidency. The election’s first clear message, then, was a resounding negative reaction to the government’s aspiration to change Turkey’s parliamentary system.

The second clear message of this election was the enthusiasm with which the predominantly Kurdish HDP transformed itself into a national party. Traditionally, the HDP and its political ancestors had clung to ethnic politics. They had carved out a space in the Turkish system by championing Kurdish rights.

But since the 2014 presidential election, the HDP, under the able leadership of Selahattin Demirtaş, decided to break this mold. The party began to champion a more pro-democracy rhetoric, with less specific focus on Kurdish rights. The objective was to transform the HDP into a more pluralistic and representative political platform.

To complement this approach, the party’s leadership decided to participate in the 2015 parliamentary election under a single banner, rather than as independent candidates, as in the past. This initially seemed a risky strategy, given that in previous elections Kurdish parties had received at most 7 percent of the national vote, short of the 10 percent threshold needed to enter the parliament.

But the tactic paid off handsomely. The HDP received 13 percent of the national vote on June 7, surpassing the expectations of even the most optimistic observers. The group is projected to become the third-biggest party in the Turkish parliament, with 81 seats, ahead of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which looks set to receive 80.

So what now? There seem to be three tangible coalition possibilities. The first two involve the AKP. The ruling party could decide to partner with either the MHP or the main opposition center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP). Although the first option may seem more plausible given the ideological affinities between the AKP and the MHP, the pairing’s main predicament would likely be its failure to advance the talks on resolving Turkey’s Kurdish problem.

As the AKP may be keen to keep the talks alive and stop the erosion of its own support among the Kurds, a so-called grand coalition with the CHP could instead become a reality. Such a coalition would need to reopen the corruption cases that were blocked under the previous government. In any case, with its parliamentary majority gone, the AKP cannot prevent these cases from being investigated if the other parties decide to pursue this course of action.

Finally, there is the option of a minority government composed of the CHP and the MHP, supported by the HDP. But minority governments have never been popular in Turkey. So as perplexing as it may seem, I would bet on the grand coalition for Turkey. How that partnership will perform is the subject of another blog post.

From a Western standpoint, Turkey’s legislative election on June 7 will be remembered as a remarkable show of dignity by the voters. After a campaign marred by violence and deaths, by a polarizing narrative from the ruling party, and by a demonization of the pro-Kurdish party, both the polling and the vote count went smoothly, and the voters’ wisdom was abundantly clear.Turkey in effect had two elections in one: the parliamentary vote itself and an indirect referendum on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s proposal to introduce an executive presidency. As a result, the country saw two complementary results: the political landscape has been substantially rebalanced, and the president’s project has been clearly rejected. The voters’ ability to freely express their preferences had a moderating effect, as is expected in modern democracies.

Whatever the length and depth of the uncertainty ahead for Turkey, (some of) the four political parties now represented in the parliament—the religious-conservative AKP, the Kemalist CHP, the nationalist MHP, and the (initially) Kurdish-rooted HDP—will have to find a way to put a government together. That is just as in any European or Western democracy, in which those in power alternate from time to time.

For all the AKP’s narrative of conspiracies driven by foreign powers and the media, the bare truth is that twelve and a half years of single-party government led to too many one-sided policies and decisions for Turkey’s citizens to bear for much longer. Again, this is exactly what voters do in the EU.

As much of a shock as this may be for AKP politicians, a European observer sees only genuine, nationally driven political normalcy in this result. Such a rebalancing of political forces can only be seen as positive by EU leaders, who have been worried by the authoritarian evolution of Turkey’s leadership during the past few months and by the rolling back of the rule of law architecture over the past year and a half.It is too early to say where political negotiations will lead—to a coalition of one kind or another, or to fresh elections. But it is early enough to say what EU leaders will watch for in a coalition agreement or in a future election campaign. Four questions stand out.

First, how swiftly and deeply will the rule of law be reinstated, in particular the independence of the judiciary?

Second, how seriously will the freedom of the media be restored and its permanence guaranteed, whatever the political situation?

Third, how comprehensive will the next government’s economic proposals be, especially with regard to the central bank’s independence, a crucial ingredient for successful foreign investment?

And finally, how compatible will Turkey’s future foreign policy be with Ankara’s Western anchor? This applies particularly to the fight against the self-styled Islamic State, to the resolution of the deadlocked division of Cyprus, to Turkey’s relations with Armenia, to Ankara’s commitments as a NATO member, and to the technical and political criteria for Turkey’s EU accession negotiations.