By Griff Witte, Michael Birnbaum and Anthony Faiola, Washington Post

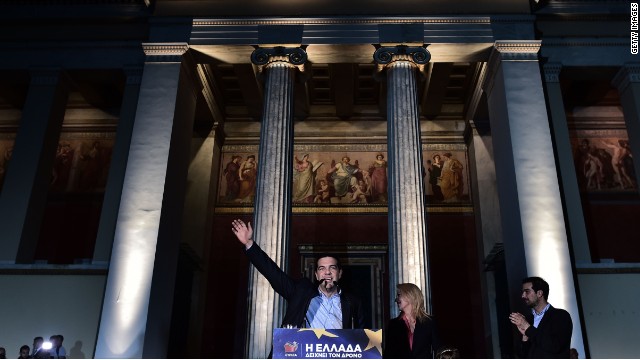

On a January evening four days before he became the first radical leftist to lead a country in the European Union, Alexis Tsipras bounded to the stage at an outdoor rally in a grubby corner of Athens and proclaimed the imminent end to “our national humiliation.”

Evidence of Greece’s severely degraded state was all around: the graffiti-saturated walls, the abandoned storefronts, the tattered clothes of the thousands who had turned out that night to cheer a man who vowed to not only remake Greece but also transform all of Europe by inspiring leftist movements continent-wide.

“First we take Manhattan,” blared the anthemic rock song radiating from loudspeakers as the boyish-looking 40-year-old paced the stage and punched the sky, “then we take Berlin.”

Six months later, those heady ambitions have shattered on the hard reality of a European status quo that has fought Tsipras’s revolutionary dreams at every turn.

The showdown between Greece’s scruffy Marxist renegades and the continent’s dour, slick-suited titans may have been an epic clash of cultures, ideologies and values that resonated around the globe.

But it was also a profoundly lopsided fight: After months of poisonous battles, the European powers-that-be are shaken but still standing, while Greece’s humiliation may be only just beginning.

“In this struggle between David and Goliath,” said George Kyritsis, a member of Parliament from Tsipras’s Syriza party, “Goliath wasn’t going to show any weakness.”

Neither was David, at least at first.

The effort to rescue this drowning Mediterranean nation, which despite its illustrious history had deteriorated into a debt-ridden pariah, has always been about more than just Greece.

For the ragtag collection of leftist professors, activists and PhD students who took office on a wave of anti-austerity anger in January, it was just the first front in a much wider campaign to claw Europe back from the heartless, neo-liberal dogma that seemed to have permeated every power corridor on the continent. If Syriza could win concessions for Greece, then that might spur similar leftist movements in Spain, Ireland, Portugal and beyond, and in the process reshape European politics.

To the faithful, Syriza’s rise from fringe player to party of government was, in itself, evidence of Europe’s failure: After decades of electing centrist governments, the Greek middle class was falling away as the austerity-choked economy shrank more than that of any other developed nation since World War II. Desperate for answers, the increasingly proletarian public looked in an unlikely place.

The new government’s prescription was to tear up Greece’s colossal bailout deals and dare Europe to offer its loans with fewer of the strings that party officials believed were strangling the economy. The strategy may have been radical, but officials thought their proposals were sensible, and they expected that Europe would soon yield.

“Syriza’s agenda was actually very moderate. It was an Obama-type program for growth,” said Kyritsis, who in addition to representing Syriza in Parliament edits a party-affiliated newspaper. “I myself am a communist, but I know we can’t put forth a communist agenda in Europe in the 21st century. We had to find a way to coexist with the mainstream.”

But where the Greek government saw moderation, Europe saw a dangerous determination to break the rules.

“Being pro-Europe means common rules and regulations that you commit to and implement,” said Finnish Finance Minister Alexander Stubb, whose country took one of the hardest lines in talks with Greece. “It’s anti-European not to stick to the rules and regulations. That might be a slightly Calvinistic approach, but that’s how I see it.”

Greek negotiators described a clash of cultures that from the beginning put them at a disadvantage against their buttoned-down European counterparts. Few on the Syriza team had a detailed understanding of the thick technical memorandum that was the guiding force of the austerity they had campaigned so hard against, negotiators said. Instead, many of the newly elected officials, energized by their fresh victory, wanted to talk in sweeping philosophical terms.

In frigid February, when negotiators sat down across from each other for the first time, the members of the Syriza squad, some of whom were still in their 20s, were abuzz with ideas about putting struggling workers ahead of corporate interests.

Their counterparts from European finance ministries and the International Monetary Fund wanted bloodless numbers. What were Syriza’s concrete proposals? And how would they affect Greece’s bottom line?

Sometimes they were scarcely speaking the same language, as worldviews clashed and tensions started to mount. Syriza’s top negotiators were fresh out of posts as Marxist-oriented economics professors. Their aides were PhD students, steeped in the heady discussions of the academy. The European side, meanwhile, was unaccustomed to hearing rhetoric that had died out of the political mainstream with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

“The Europeans thought these were normal politicians who would turn after the elections. These guys were really hard-core,” said one former negotiator from the Greek side, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the difficulties of the months of fruitless talks.

Even words like “competition” — hardly controversial among the market-driven economic elite that Syriza sought to reshape — irked some of the Greek negotiators, the former negotiator recalled. Syriza bosses saw the relentless focus on promoting growth as prizing profits over people.

Greece’s strategy had been premised on the idea that it could peel away allies to advocate on its behalf against an austerity-minded European establishment dominated by Germany. But instead, some of the continent’s smallest nations became its fiercest critics.

Officials from Eastern European countries that suffered for decades under communism warned of the dangers of giving in to the left.

Other countries wrestling with their own economic troubles marveled that a nation receiving so much support could be so seemingly oblivious to the impact of the bailouts beyond its own borders.

“People need to understand that a country like mine has contributions to Greece that are nearly 10 percent of our annual budget and 2.5 percent of our GDP,” said Stubb, the Finnish finance minister. “We’re not talking about small potatoes.”

An analyst familiar with German thinking said Greece’s former finance minister, the self-styled bad boy Yanis Varoufakis, made a key error in gaming the Germans. Rather than shrink from Varoufakis’s increasingly bitter accusations of German malice, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble only hardened his line, convinced that the Greek government could not be trusted.

Schäuble’s conviction was deepened after Tsipras walked away from the negotiating table on June 26 and called a national referendum on Europe’s proposal, urging the public to vote no.

“Tsipras really thought that a clear ‘no’ in the referendum would strengthen his position in the negotiations in Brussels,” said Marcel Tyrell, a professor of economics and game theory expert at Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen, Germany.

But instead of winning leniency, the no vote prompted European negotiators to toughen their terms while threatening that further Greek intransigence would lead to swift bank failures and an ejection from the euro zone.

With Greeks already lining the streets to get their daily 60-euro ATM withdrawal, Tsipras relented — agreeing last Monday to measures tougher than the ones on the table before the referendum, or than the ones he had denounced so forcefully while campaigning in January.

In the end, the Greek side may simply have overestimated its strength. Greece was unwilling to leave the euro. As the bargaining stretched on, the increasingly furious European side was all too happy to bid farewell.

“We never actually had a plan B” if Greece were forced off the euro, said one of the negotiators. “What could we have done, really? Maybe our threats were a bit like a bee’s. You sting, you hurt someone a bit, but then you die.”

The agreement allowed Greece to stay in the euro zone — at a very high cost. But it was still not as tough as some hard-liners, led by Germany, would have liked. They remain skeptical that Greece will fulfill its end of the bargain.

“It is extremely difficult to believe that a new program is going to be followed by a government that openly says it doesn’t want it,” the European official said.

Even if European nations are not sure whether they won the showdown, Greek officials readily acknowledge that they lost, saying they believe they were made an example of so that other European nations would not dare elect their leftist allies.

“It’s not an agreement, it’s a punishment,” said Deputy Culture Minister Nikos Xydakis. “Their plan is fear.”

In the wee hours of Thursday, Tsipras persuaded the Greek Parliament to back the deal even while proclaiming that it will inflict additional pain. His decision to support the agreement has split his consensus-minded party, raising questions over whether the rift will ever heal.

Some within the government see the past week as only a temporary setback and are still counting on elections in Spain and Ireland within the year to deliver sorely needed leftist allies.

“It was a tactical retreat to avoid the sudden death of the economy,” said George Katrougalos, the labor minister. “We had confidence that we could change Europe. I still believe we can do it. We just thought it was going to be easier than this.”

Others are less sanguine.

Kyritsis, a 50-year-old whose hoop earring and pointy gray beard give him the bearing of a beat poet, was sworn in as a member of Parliament only on Wednesday, just in time “to vote for something I despise.”

The next day, he wrote on Facebook that he was embarrassed. In reply, people called him “a traitor.”

He could understand why. Having doubted his whole life that he would ever see a leftist government in Greece, he voted yes only to save it from falling after a mere six months.

But he wonders whether a disenchanted public will swing again — this time to the far right. And he despairs that the dream of a more equitable and compassionate Europe may be dead, at least for the foreseeable future.

“For my generation and for the younger generation,” he said softly, “it’s over.”

Faiola reported from Berlin. Stephanie Kirchner in Berlin and Karla Adam in London contributed to this report.