By Arne Delfs & Alan Crawford, Bloomberg

It was when the numbers became faces that German Chancellor Angela Merkel made a decision that could make or break her political legacy.

As she toured a refugee center in the eastern German town of Heidenau on Aug. 26, hearing stories from Syrians about traumatic journeys to flee their civil war, protesters against their arrival jeered and shouted abuse. Some called her a “traitor to the nation.” The experience left her shaken but determined to act, according to two close Merkel aides.

What ensued was a strategy for dealing with a flood of refugees by simply letting them come. While her open-door policy transformed her image almost overnight from the scourge of the Greeks into the conscience of Europe, it threatens to split the continent and presents a domestic high-wire balancing act even more dramatic than the euro crisis.

“If we now have to start apologizing for showing a friendly face in response to an emergency situation, then that’s not my country,” Merkel said at a press conference in Berlin on Tuesday.

Willkommen

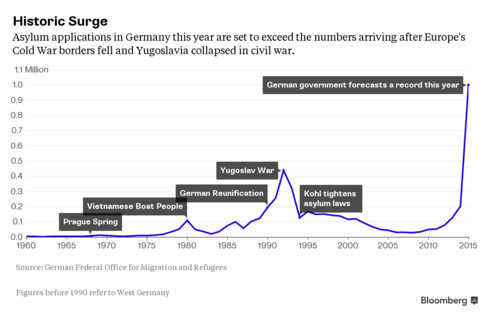

Germany, already a magnet for job seekers from Spain, Greece and Italy, became the destination of choice for refugees as word got out they were welcome. Interior Ministry estimates of 800,000 of them this year became 1 million arrivals in a forecast this week by Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel, though not all will end up staying.

While Germany’s economic growth and near-record low unemployment gave her some breathing space, her European counterparts were already struggling with sluggish economies and angry constituents.

She called for European “solidarity,” echoing words she used during the debt crisis as shorthand for a financial rescue. This time, she meant a fair distribution of refugees among EU member states.

For Merkel, “the risks are more longer-term” as new arrivals compete for jobs and housing in Germany, potentially feeding popular resentment, said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank. “The political reaction to the refugee crisis is potentially a much bigger risk to Europe” than Greece, he said. “These are significant risks that strike at the heart of the EU.”

Remembering 1989

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban was having none of it. Hungary, which is one of the main EU arrival points along with Italy and Greece, blocked thousands of refugees at the border with Austria.

Merkel’s response on Sept. 5, to open the doors further to alleviate the bottleneck, was motivated not only by fear of an open border conflict. Her policy took on an added emotional dimension as she was reminded of similar scenes at the Hungarian border in the summer of 1989, when East Germans queued to make their way onward to the West, according to one of the aides.

For the Lutheran pastor’s daughter, the refugee crisis is a humanitarian catastrophe that must be addressed, the people said. It also could be a defining moment that offers a chance to permanently alter Germany’s image as the cold head, rather than the heart, of Europe.

“She sees perhaps an opportunity here to appeal not only to other EU leaders, but to send the more general message that we are bigger and better than this,” said Jackson Janes, president of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies in Washington. “But this could also be another of her efforts to rally the EU, after a long bad patch with Greece where Merkel made a lot of people angry.”

Political Warnings

Within Germany the backlash has been swift too. Her Christian Democratic Union party offices are getting hundreds of e-mails and letters each day critical of the chancellor’s approach. The aides and party officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said she is aware that if Germany fails to get the refugee crisis under control and to integrate the Syrians into German society, she will get the blame.

Merkel, 61, is facing a nascent rebellion from the CDU’s sister party in Bavaria, the main point of entry for refugees coming across the Austrian border. Bavarian Prime MinisterHorst Seehofer, who criticized Merkel’s decision to allow in refugees from Hungary as a “mistake that will occupy us for a long time to come,” said Monday that some districts of his state are taking in more refugees than all France.

Some senior party members are said to be appalled by her open-doors policy. They were incredulous at her suggestion in a newspaper interview last week that she can’t impose limits on the number of asylum seekers Germany will accept.

After defending her decision to allow entry for thousands of unregistered refugees, Merkel may have bought some time with the reintroduction of some border controls and she has public opinion on her side for now. While 35 percent of respondents said Germany is being overwhelmed by refugees, 62 percent said the country can handle the influx, according to a Sept. 8-10 FG Wahlen voter poll for ZDF television.

Teflon Chancellor

Yet as she listens to warnings about driving voters into the arms of the far right, it’s still by no means certain she’ll be able to carry the German people with her. Ten years in office and midway through her third term, the refugee crisis might be the Teflon chancellor’s undoing as the nation heads toward the 2017 election.

And still they keep coming. The Foreign Ministry was expecting 40,000 people to arrive in Germany last weekend alone — double the number the U.K. will accept over the next five years.