By Zaman

On Sept. 20, Greece held its national election for the second time this year. The result was a great victory for the Syriza Party and its leader Alexis Tsipras, despite the fact that several of the party’s high-profile members left prior to the election and established another party, which, as it turns out, marginally missed the threshold to make it into the new parliament.

The coalition government that was formed after the Sept 20 election was comprised of the same parties as before — the leftist Syriza and the (far) right Independent Greeks (ANEL) — resulting effectively in a very similar setting to the one pre-existing the September election.

A first reading into the results would lead to the assumption that the second national election of 2015 brought about very little change when compared to the first one in January. However unexciting, this is still an important finding. So many things have happened in the past months in Greece — a referendum, the closing of the banks, the party splits, the changes in party leaderships etc., — that some would expect more groundbreaking electoral changes, almost by default. Take the ruling party Syriza, for example. After having based literally all of its rhetoric — from the start of the crisis to its victory in the January 2015 election — on an anti-austerity program, it signed a new agreement with the lenders. It included heavy austerity measures, which have to be implemented in a very short time and will actually lead to two more years of recession, contrary to the growth figures projected by the agreement that the previous government negotiated. Still, Syriza managed to concentrate 35.46 percent of the vote, losing less that one percentage point in popular support. Taking the party split into consideration, someone could actually argue that Syriza gained rather than lost.

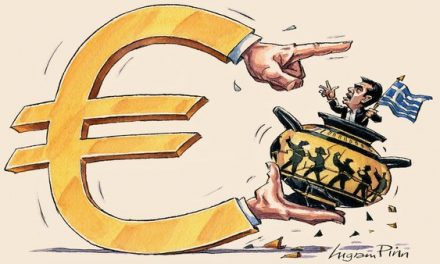

Despite the similar results, and the more-or-less same government that turned up after the Sept. 20 election, I still think that the election has brought significant change. It is just not a change concerning who it is that the people vote for. Instead, it regards the changes of the political parties themselves, especially regarding Syriza. This is why the change is invisible in a simple reading of the election results. More specifically, with Syriza now arguing that the best way to face the crisis is with the help of both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European institutions, it is the first time that the vast majority of Greek people voted for parties which favor a solution to the crisis that would happen through a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Greece’s lenders. To put in numbers, 267 MPs out of 300 in the Greek parliament support, at least in theory, such a solution.

This significant turn presents the country with significant challenges and opportunities. With such a great parliamentary support, the Syriza-led coalition should be able to take the necessary steps to allow the Greek economy to finally exit recession and follow the path to development, as other countries which faced similar challenges did — such as Spain or Portugal. Still there are many, myself included, that are skeptical about whether the Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras will manage to implement all the necessary, and at the same time partly unpopular, reforms. It is not only that he did not seek a coalition to include more parties, which would potentially improve his negotiating position against his European partners. The main suspicion is over his and his party’s commitment to the implementation of the new bailout program and the fact that it is quite limited and yet to be proven.