Whenever pro-Palestine Egyptians raise the issue of their country’s non-interference in the Palestinian conflict and blame is casted on the current regime or those of the past, there is usually no shortage of people attacking the Palestinians (occasionally with astonishing zeal) and blaming them for their current misfortune.

Of all the arguments thrown around, the most provoking is the one accusing the Palestinians of selling their historical homeland and not actively resisting the influx of Zionist settlers. As an indisputable fact, the historical treason of the Palestinians to their own cause has been continuously affirmed throughout the years to the extent that it became part of the Egyptian popular culture in relation to the Palestinian cause and one of the popular justification tools to support the unbearable passiveness of Egypt in the conflict, despite the repeated massacres and continuous injustice suffered by the Palestinians. A brief (somehow selective) summary of the history of Palestine from the start of Zionist immigration in the 19th century till the first Arab-Israeli War of 1948 will demonstrate that besides not giving up their lands willingly, Palestinian Arabs were active in both popular, political and armed resistance from the time of the Ottoman rule till the end of the British Mandate.

The land problem in Palestine started with the Ottoman Land Laws of 1858 and 1861 that made it mandatory to register communally owned land in the name of individuals who were to become liable to pay taxes to the Ottoman authorities. Many of the typically poor Palestinian land inhabitants, fellahin, did not understand the importance of registers and therefore did not register the lands they had historically inhabited with their names under the new laws. In other cases, the fellahin who had registered the lands in their names became unable to pay the taxes leading to their land being confiscated or forcing them to sell it to wealthy individuals and ultimately become tenants on the lands they had inhabited and farmed for hundreds of years. This resulted in the appropriation of large tracts of lands in Palestine by absentee wealthy non-Palestinian Arabs in Damascus and Beirut and to a lesser extent rich families in Jerusalem and Jaffa. By the end of the 19th century, when the population of Palestine was about 600,000, only 250 individuals owned 45% of the cultivated land in Palestine. When the Zionists started to purchase lands in Palestine at this period, it is quite understandable that they favored buying from those wealthy individuals who were not attached to the land and did not inhabit it. In many of the cases, the Zionists also concentrated their purchases in the sparsely populated uncultivated coastal plains to avoid confrontation with the original inhabitants.

From the very beginning, Palestinian Arabs were aware that the influx of Zionist immigrants was a threat to their homeland. A few years after the first wave of Zionist mass immigration (aliyah), and the establishment of the first political Zionist colony, popular resistance in Palestine was initiated. The fellahin, fearing evacuation and displacement from the lands bought by Zionists, held protests in 1886 against the expansion of the settlement of Petah Kitva which resulted in the Ottoman government restricting the settlement of those who entered the lands as tourists and stayed for more than three months. With the spread of Zionism as an ideology and the gradual but slow increase in the lands purchased by the Zionist settlers, there were many acts of political resistance within the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire. Palestinian notables and intellectuals repeatedly raised the issue in the Ottoman Parliament and managed to convene several commissions under governmental authority to study and prevent Zionist immigration. These efforts succeeded in preventing immigration and land purchases from 1897 to 1902. After publishing was legalized following the Young Turks coup d’état in 1908, several publications were launched to expose Zionist plans and call for the awakening of the Arabs with the most influential one being Filastin, which was forcibly closed on several occasions after British control began to intensify. One of the Arab journalists of this period, Najib AlKhoury, had been so concerned with attacking Zionism and raising awareness with regards to its goals that he was nicknamed Magnoun Al-Sehyouneya (the one obsessed with Zionism). By the beginning of the First World War, the popular and political resistance of the Palestinian people had succeeded to limit all Zionist land purchases to less than 1.6% of the total area of the future British Mandate. Of the lands purchased, 58 per cent were made from absentee non-Palestinian landowners, 36 per cent from absentee Palestinian landowners and the remainder from local wealthy families and the fellahin.

By the end of the First World War, the Palestinians felt betrayed. The Arab Revolt of 1916-1919 had been initiated in coordination with the British based on the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence in which the Brits had promised the Arabs their independence and the lands of Al Hijaz and Al-Sham (including Palestine) if they rose against the Ottomans. This promise made to the Sharif of Mecca was soon reneged by the British in the secret Sykes-Picot agreement between Britain and France which was followed by the occupation of Palestine by British troops in 1917. In the same year, after victory was almost secured by Britain and its Arab allies on the Near Eastern front and with the Western Front on a stalemate, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration promising to support the aspiration of Zionists to establish a national home for the Jewish People in Palestine. The declaration was made in order to secure financial resources and appeal to American Zionists (two of whom were close advisors to the United States president) in the last phase of the war.

At the time of the declaration, Palestinian Arabs constituted 90 per cent of the population and the Zionists held only 1.7 per cent of the lands of the future British Mandate of Palestine. In response, Muslim and Christian Palestinian Arabs held a meeting and adopted a platform calling for a representative government while endorsing opposition to the Balfour Declaration and Zionism in what was later referred to as the First Palestinian National Congress. When it became apparent after the end of the war that the British had no intentions of leaving and were also favorable towards Zionism, the Palestinians initiated major demonstrations and riots in the early 1920s with one of them coinciding with the visit of Winston Churchill. They attempted to block his train. Many Palestinians were killed in these events as British troops opened fire on more than one occasion. The riots eventually led the British to compromise and issue the White Paper of 1922, later called the Churchill paper, confirming that “the status of all citizens of Palestine in the eyes of the law shall be Palestinian” and calling for the limitation of Jewish immigration to Palestine.

With the British mandate officially endorsed by the United Nations in 1923 and the sustained increase in Zionist immigration and settlements despite the Churchill Paper, Palestinian resistance continued and intensified in the second part of the 1920s leading eventually to the large scale Buraq uprising in 1929. The demonstrations started in response to the Zionist settlers violating both tradition and British policy by erecting a partition and a wall at a section of the Haram Al-Sharif with rumors circulating that they would take control of it. The British police eventually suppressed the riots with the killing of more than one hundred Palestinian Arabs.

The Buraq uprising led the British to reconsider their policy and issue a second White Paper criticizing the ejection of Palestinian peasants from the lands bought by the Zionist settlers and calling for some restrictions on Zionist immigration and the sale of lands in Palestine. In response, Zionist organizations worldwide mounted a vigorous attack on the document leading Britain to issue in the following year a clarification, which made the content of the paper ambivalent. At the same period, the Palestinians established the “Black Hand”, an anti-Zionist anti-British militant organization and in 1933 there was another popular uprising and demonstrations against Zionist mass immigration. The continued favoritism by the British towards the Zionists and the rise of Nazi Germany had resulted in a notable increase in Zionist immigration and land ownership in the following years. By 1936, the lands owned by the Zionists had almost tripled from the end of the First World War to reach 4.6 per cent of the total area of the British Mandate. The Palestinians were incensed and it was the killing of Ezz el Dine El Qassam, the founder of the Black Hand, who was trying to spark an organized armed revolt in Palestine, by the British police that eventually sparked the famous 1936-1939 second Arab Revolt.

The events of the Great Arab Revolt started with a nation-wide general strike that lasted for almost six month and was considered by some as the longest general strike in history before turning to a general armed uprising in the spring of 1937. The Palestinians effectively took control of large areas of land from the British including the older parts of the cities of Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus. Tens of thousands of British troops had to be employed and the revolt was suppressed with difficulty over a course of 18 months of intense fighting by the combined forces of the British Army and the Zionist bands at the catastrophic loss of more than 5,000 Arab lives. In total, 10 per cent of the adult Arab male population had been killed, wounded, imprisoned, or exiled by the end of the Great Arab Revolt, with the high proportion of casualties being the experienced military commanders and the most unyielding fighters, a loss that would prove vital in the following years. In contrast, the Zionist paramilitary bands had benefitted considerably from the significant assistance in armaments and military organization resulting from their cooperation with the British against the Palestinian Arabs. By the end of the revolt, 6,000 Zionist fighters were helping the British Police suppress the last Palestinian resistance.

Despite being brutally crushed, the massive and bloody Great Arab Revolt is credited with leading the British to issue another White Paper in 1939. Unlike the first two, what came to be known as the Macdonald White Paper was more definitive. It clearly rejected the idea of the creation of a Jewish state and the partitioning of Palestine. In addition, it limited yearly Jewish immigration to 15,000 for 5 years, ruled that further immigration was to be determined by the Arab majority in Palestine, and called for an independent state with an Arab majority to be established within 10 years, which was a severe blow to Zionist efforts. The result was that the Zionist settlers refused to abide by the White Paper of 1939 organizing in the following years a series of illegal immigration that intensified with the Jewish persecution in Europe. The Zionist paramilitary bands supported this effort by conducting a series of attacks against both the Arabs in Palestine and also the British forces, now considered an enemy, leading the United Nations to describe the most prominent of them as a terrorist organization. By 1945, official studies by the Anglo-American Committee revealed that the Zionist settlers had acquired 1,393,531 dunams of land, of which roughly 850,000 dunams had been purchased under the British Mandate, and the rest when the area had been under Ottoman control. This constituted about 5.3 per cent of the total land area of mandatory Palestine. In all, it is estimated that the Zionist settlers held 7 per cent of the total area of the British Mandate of Palestine by June 1947.

With the Mandate officially ending in the following year, the Zionist lobby had been underway to accomplish its foremost success to date by leading the United Nations to adopt a resolution in November 1947 recommending the adoption and implementation of a partition plan in Palestine to establish independent Arab and Jewish states while assigning the administration of Jerusalem-Bethlehem to special international administration. Harry S. Truman, the president of the United States at the time, later noted in his memoirs that the pressure movements around the United Nations and the White House with the constant barrage and propaganda of the Zionist lobby had been unlike anything he had ever seen before and that the persistence of extremist Zionist leaders and their political threats had deeply “disturbed and annoyed” him.

The Zionist lobby had been too effective to the extent of pressuring the United States to bribe or threaten many countries including Liberia, Philippines, Haiti and France (the latter in need for American aid for reconstruction after World War II) with cutting financial aid if they did not vote for the partition plan which eventually succeeded. Other countries like Cuba and India voted against the resolution while publicly announcing that they had been pressured by the United States and the Zionist lobby but had refused to abide. The prime minister of India publicly spoke with anger and contempt for the way the UN vote had been lined up. He said that the Zionists had tried to bribe India with millions and that at the same time his sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, had received daily warnings that her life was in danger unless “she voted right”. The result was the infamous UN Partition Plan of 1947, which granted the Zionist settlers, comprising less than third the population of Palestine at the time of the plan, 56 per cent of the lands of the British Mandate including areas where Arabs were living as opposed to the 7 per cent they had previously held.

No surprise, the adoption of the UN partition plan in 1947 led to massive Arab protests, a general strike and finally a full scale conflict between the Palestinian Arabs (whose fractioned forces were still suffering from the previous Arab Revolt with many of their leaders killed in action, executed or exiled) and the Zionist paramilitary bands. At the end, it was the Zionist bands that gained the upper hand after committing several massacres against the Palestinian population, most notably the disgraceful attack on the village of Deir Yassin in which more than 254 peaceful and unarmed Palestinian villagers were killed including children and women as counted by an International Red Cross official and reported in the New York Times. The defeat of the Palestinian forces, the intense bombardment of heavily populated urban areas and the news of the indiscriminating massacres by the Zionist bands against unarmed villagers traveled throughout Palestine resulting in a state of panic, an initial massive exodus of around 400,000 Arabs expelled or leaving their homes to escape the killings and a general collapse of the Arab society in Palestine.

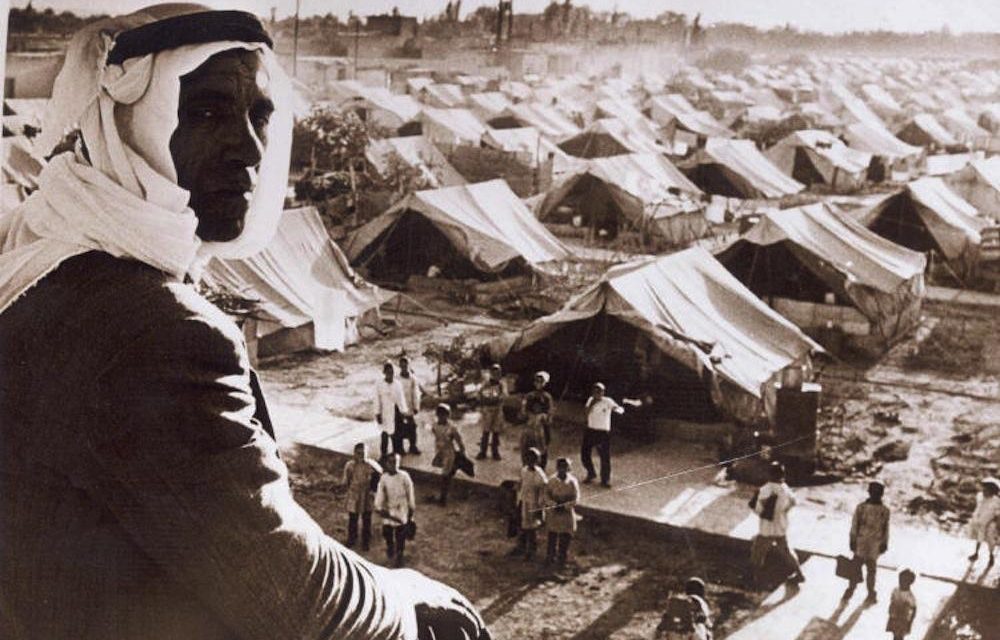

The events eventually led to the first intervention by other Arab states in the conflict and their defeat in the first Arab-Israeli war commonly known as the “Nakba” which resulted in Israel occupying even more territory bringing the total area under Zionist control in 1949 to 77 per cent of the lands of the British Mandate of Palestine.

By that time, the total Palestinian exodus amounted to 750,000 out of a total population of almost 1,300,000 marking the start of the tragedy of Palestinian refugees and their unquestionable legitimate right of return. Enough to say that in the seven years following the war, between 3,000 and 5,000 Palestinians were executed on the spot by the Zionist bands as they attempted to infiltrate and return to their homes and lands, so much for a people who had given up their lands willingly. To add to the plight of the Palestinian national cause, Transjordan which had initially participated in the war with its own agenda of territorial expansion and against Palestinian wishes formally annexed the area west of the Jordan River which it had occupied in the war calling it the West Bank while Gaza became under Egyptian administration with a nominal Palestinian government. As a result, the Palestinians held no effective control over any lands after the first Arab-Israeli war as opposed to them holding most of the lands under the British Mandate and before the United Nations Partition Plan.

No words can describe the anger and frustration felt by some Egyptians because of the passiveness of their country in the Palestinian conflict especially after the Camp David Accords or the current disgraceful and criminal participation in the Gaza blockade. Having said that, since the past ruling regimes of Arab countries had directed all their efforts and resources to remain in power without caring for the plight of the Palestinians or Israel’s continued disregard to humanity and international law, one can understand if a fellow Egyptian or Arab considers it practically unwise at the moment for his or her country to actively support the Palestinian struggle based on limited military or economic capabilities. But, instead of swallowing the shame, for some people to support and justify this non-interference by accusing the Palestinians of historical treason and trying to demean an oppressed struggling people who have sacrificed and continue to sacrifice for their national homeland till this very day is just unbearable.

***

Any views expressed are the author’s own

***

Sources and further reading:

Dunam is a measure of land area used in parts of the former Turkish Empire equal to about 1000 square meters. All percentages of land ownership are assessed based on the area of the British Mandate of Palestine being 26,320,505 dunams as stated in “A Survey of Palestine” which was “the official research prepared by Government of Palestine (then under British military occupation/Mandate) for the United Nation Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) in 1946.”

Mazin B. Qumsiyeh, Popular Resistance in Palestine, a History of Hope and Empowerment

Stein, Kenneth W., The Land Question In Palestine, 1917-1939

Gelvin, James, The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War

Eugene Rogan and Avi Shlaim (eds.) Palestinians and 1948: the underlying causes of failure. In The War for Palestine

Moshe Aumann (1976), Land Ownership in Palestine 1880-1948 (Israel Academic Committee on the Middle East).

Quigley, John B. (1990). Palestine and Israel: a challenge to justice

Barr, James (2012). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle that Shaped the Middle East

Heptulla, Najma (1991). Indo-West Asian relations: the Nehru era

Ilan, Pappe (2006). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine