ISIS might have pulled off a string of terrorist attacks across Europe in recent months, but on its home turf in Iraq and Syria it has suffered one setback after another.

By Zachary Cohen and Ryan Browne

On Monday, Syrian forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad recaptured the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. Last week, the U.S. took out the organization’s No. 2, Abd al-Rahman Mustafa al-Qaduli, whom the Pentagon dubbed ISIS’ “finance minister” and is just the latest target to disrupt the group’s financial network.

And in recent months, the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition has killed more than 10,000 fighters and 20 leaders, including al-Qaduli, according to Pentagon estimates.

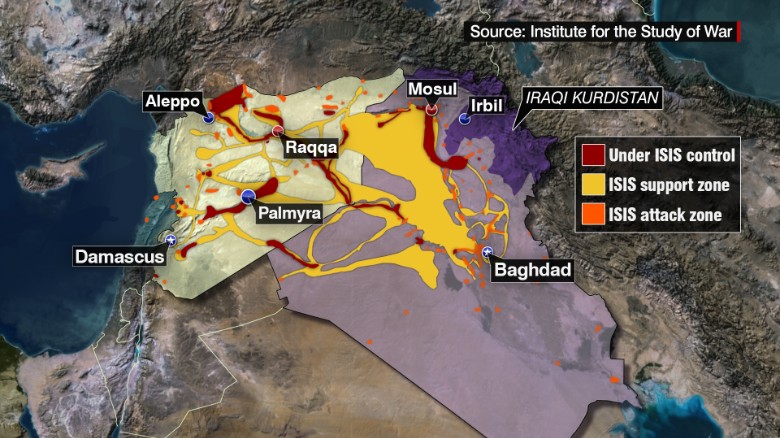

Altogether, the U.S. calculates that ISIS has lost 40% of the 34,000 square miles of territory it controlled in Syria and Iraq before the U.S. and a host of other nations ramped up military involvement in the region in 2014. Perhaps most significantly, Iraqi forces retook the city of Ramadi in December.

The Pentagon has tried to draw more attention to the group’s losses, which officials believe are considerable.

“We are systematically eliminating ISIL’s cabinet,” Defense Secretary Ash Carter said last week, using a different name for ISIS. He noted that al-Qaduli was “the second senior ISIL leader we’ve successfully targeted this month.”

Asked whether the U.S. was turning the corner on the fight against ISIS, Carter responded, “We’re certainly gathering momentum and we’re seeing that that momentum is having an effect.”

ISIS increasing attacks on Westerners?

But could that anti-ISIS momentum on the ground in the Middle East be spurring the group to stage more terror attacks in Europe, such as the one Tuesday that claimed at least 35 lives in Brussels? Is the group looking to distract from its losses of territory and leadership and show that it still has the ability to inflict as much pain — and is as dangerous to the West — as ever?

“ISIS has definitely faced losses and has increased its use of unconventional tactics, like suicide bombings, in order to draw forces away from the front,” said Harleen Gambhir, a counterterrorism analyst at the Institute for the Study of War.

“But linking the recent terrorist attacks in Brussels to ISIS’ battlefield losses misses the point,” she added, noting that ISIS has “been attempting to execute a global campaign for years” and “external attacks are key to its ideology.”

Some of the land ISIS has surrendered has also been tactical, according to Gambhir, as the group has chosen to yield territory in the face of potentially heavy ISIS fighter casualties.

Still, the fact that two mass casualty attacks of the scale of Paris and Brussels have occurred since coalition efforts have started reclaiming areas once considered part of ISIS’ “caliphate” is telling, according to Nick Heras, a Middle East expert with the Center for New American Security.

“ISIS fancies itself as a state with the power to deter its strategic enemies and to coerce their behavior, and the external attacks in Europe work towards this goal,” said Heras, pointing out that the group also understands that conducting these attacks in the West will potentially lead to more aggressive efforts from the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq and Syria.

He continued, “The West should expect that ISIS has developed a contingency strategy to authorize more attacks inside of Europe even in the event that its would-be caliphate is collapsing in Iraq and Syria, and that even in its dying days ISIS’ proto-state will try to punish Western countries that hastened its end.”

The U.S.-led coalition long focused primarily on airstrikes but has recently expanded its efforts to take on ISIS more aggressively.

The U.S. military’s elite Special Operations forces began on the ground missions to target, capture or kill top ISIS operatives in Iraq last month.

In the wake of the Brussels attack last week, Defense Secretary Carter vowed to further “accelerate” efforts to destroy the extremist group and its caliphate by conducting “raids of various kinds, seizing places and people, freeing hostages and prisoners of ISIL, and making it such that ISIL has to fear that anywhere, anytime, it may be struck.”

Criticism of air strike strategy

The air campaign faced criticism that it was not doing enough to alter the trajectory of the anti-ISIS effort.

Chris Harmer, a senior military analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, called the air campaign “tactically spectacular but strategically irrelevant,” adding that such strikes might have had a decisive impact if ISIS followed a strict organizational structure but that boots on the ground are the key.

Yet targeting specific ISIS leaders is not intended to lead to the “immediate, or direct, collapse of ISIS as an organization,” Heras said.

While the local leadership in places like Iraq and Syria can regenerate itself and continue to operate on the ground, Heras argued that its abilities to launch mass-casualty terror attacks abroad was limited by taking out leaders, as the attacks on the West require a bigger, more sophisticated network and coordination.

This significantly benefits the U.S. both because it disrupts attacks against Western civilians but also because it deflates the ISIS narrative that it has been able to deter the international community by launching and coordinating attacks in the West.

“The less ISIS looks like it can act like a state, and conduct attacks in the heart of the West, the weaker its narrative to would-be jihadists that it is the epochal caliphate and therefore worthy of their allegiance,” Heras said.