By Matthew Yglesias

The “electability” question has loomed large in discussion of the Democratic primary even though it hasn’t been explicitly discussed much by the candidates. Hillary Clinton’s supporters routinely raise it as a key problem with Bernie Sanders’ aspirations. Sanders’ supporters, meanwhile, are increasingly frustrated that their candidate gets no credit from these pundits for performing significantly better than Clinton in head-to-head polling against possible GOP contenders.

But what worries the Democratic Party professionals who’ve rallied to Clinton’s side — not just her inner circle, but the vast majority of the party’s elected officials and interest group leaders, including people who are more ideologically in-sync with Bernie — isn’t Sanders’ personal standing.

It’s his ideas and, especially, his approach to politics.

Sanders’ appeal in the primary is based largely on the idea that he, unlike Hillary Clinton, full-throatedly embraces the liberal agenda and always had. Clinton supported the Defense of Marriage Act and “tough on crime politics” in the 1990s, while Sanders safely ensconced in Vermont did not. Today, Sanders calls for a carbon tax, and an end to the death penalty. He’s shattered taboos on Israel by calling openly for more “respect and dignity” to be shown to the Palestinian people.

But it’s no great mystery why Clinton’s record is different from Sanders’ in this regard. She’s a careful, opportunistic politician who is more likely to follow public opinion and lead it. That’s what makes her a less-inspiring candidate. Someone who’s less likely to attract a vast crowd to her rallies, and less likely to inspire an ordinary person to take $15 or $50 out of her wallet and hand it over to Clinton. But it’s also, in the view of most professionals, what makes her the more electable candidate. Careful opportunists win and the establishment worries that Sanders won’t be careful or opportunistic enough.

Sanders polls much better than Clinton

The basic core of the current electability case for Sanders refers to public opinion polling.

Current polls show Clinton beating both Republican front-runners rather handily, but losing to John Kasich — a potential indication that she would have problems against any kind of X-Factor nominee who might emerge from a contested convention. Sanders, by contrast, beats all three Republicans and absolutely trounces Trump.

Similarly, Clinton’s favorable ratings are dismal (though much better than Trump’s or Cruz’s) and though Sanders’ numbers aren’t great they are much better than hers.

This, in the eyes of Sanders’ supporters, amounts to a strong prima facie case that he is the real electability choice.

General election polls are starting to matter

For months, the counterpoint from Clinton’s supporters has been that early general election polls aren’t predictive. And, indeed, they aren’t. But we are starting to get to the point in the year when the polls aren’t “early” anymore and instead convey real information.

Christopher Wlezien is the co-author, with Robert Erikson of Columbia, of The Timeline of Presidential Elections, a political science book that provides an invaluable guide for anyone trying to make sense of polling data.

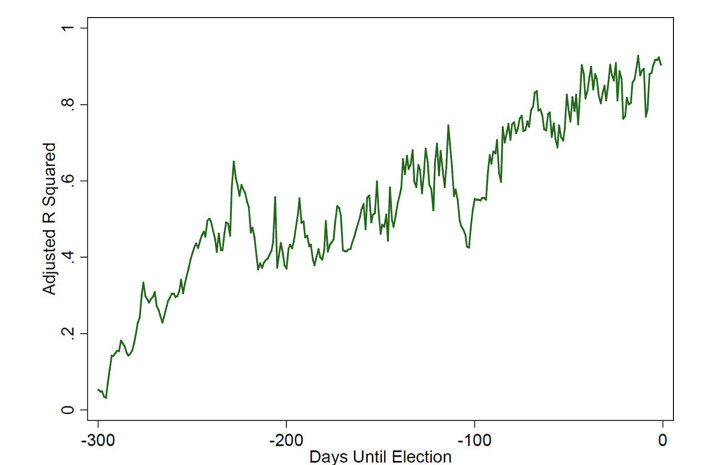

The two crunched general election polling numbers for the past 60 years of presidential contests. And the below graph shows, essentially, how closely the polls tend to be related to the eventual outcome at various points in the campaign. The higher a point is on the y-axis, the more predictive the polls for that time in the campaign:

Unsurprisingly, Wlezien and Erikson found that as the campaign goes on, the polls start looking more like the eventual outcome.

These polls may not tell us much about Sanders

But while today’s polling showing that Clinton is a not-so-popular figure and Trump a very unpopular one are probably conveying meaningful information, it’s much less clear that the rosy outlook polling offers for Sanders and Kasich is warranted.

Polls become more predictive as we get close to the election because voters hear more information about the candidates as time goes on.

The media has, thus far, given much more coverage to frontrunners Clinton and Trump than it has to Sanders and Kasich. And the coverage that has existed has primarily featured the underdogs as antagonists of not-very-popular frontrunners rather than scrutinized them on their own terms. And, crucially, neither Sanders nor Kasich has yet been subjected to sustained criticism by the opposition party.

Clinton needs to dance gingerly around lambasting Sanders as a tax hiking job-destroyer or a soft-on-crime pinko lest she divide her own electoral coalition. Republicans would have no such worries, and like any candidate his numbers would fall somewhat in response to attacks. That’s not to say they would necessarily fall as far as Clinton’s numbers but they would certainly fall.

What really worries Democratic professionals about Sanders

An exchange in the most recent Democratic debate illustrates, beyond polling, exactly what has professional political operatives worries about Sanders. Things that he brings to the table as his primary virtue in a nominating contest — primarily a willingness to take tough stances regardless of the political consequences — are likely to be weaknesses as a nominee:

SANDERS: All right, here is — here is a real difference. This is a difference between understanding that we have a crisis of historical consequence here, and incrementalism and those little steps are not enough.

Not right now. Not on climate change. Now, the truth is, as secretary of state, Secretary Clinton actively supported fracking technology around the world. Second of all, right now, we have got to tell the fossil fuel industry that their short-term profits are not more important than the future of this planet.

And that means — and I would ask you to respond. Are you in favor of a tax on carbon so that we can transit away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy at the level and speed we need to do?

CLINTON: You know, I have laid out a set of actions that build on what President Obama was able to accomplish, building on the clean power plan, which is currently under attack by fossil fuels and the right in the Supreme Court, which is one of the reasons why we need to get the Supreme Court justice that President Obama has nominated to be confirmed so that we can actually continue to make progress.

I don’t take a back seat to your legislation that you’ve introduced that you haven’t been able to get passed. I want to do what we can do to actually make progress in dealing with the crisis. That’s exactly what I have proposed.

LOUIS: OK, thank you, Secretary Clinton.

CLINTON: And my approach I think is going to get us there faster without tying us up into political knots with a Congress that still would not support what you are proposing.

LOUIS: Senator Sanders, you’ve said that climate change is the greatest change to our nation’s security.

SANDERS: Secretary Clinton did not answer one simple question.

LOUIS: Excuse me, Senator, Senator, Senator, Senator, Senator…

SANDERS: Are you for a tax on carbon or not?

Sanders is a smart politician and he tried to press Clinton on this with good reason. On the one hand, she’s not going to endorse a carbon tax. But on the other hand, if she attacked a carbon tax on its merits she’d be lambasted by the kind of wonkish establishment liberal pundits who’ve been generally supportive of her campaign and environmental groups would be compelling to slam her.

Consequently, she has no choice but to look squirrely and evasive which gives Sanders an opening to return to his insinuations that he thinking on climate change has been perilously corrupted by fossil fuel money. But it’s no mystery why Clinton doesn’t want to embrace a carbon tax — it’s unpopular.

Carbon taxes are the least-popular climate fix

According to Harvard political scientist Stephen Ansolabehere’s meta-analysis of 25 separate surveys:

75 to 80 percent of Americans favor EPA regulation of greenhouse gas emissions

45 to 55 percent favor cap and trade

25 to 45 percent favor a carbon tax

That’s why Clinton won’t embrace a carbon tax. She wants to win in November.

EPA regulation of greenhouse gas emissions is almost certainly not the optimal policy for combatting climate change. But it is popular and political defensible, as well as being something a Democratic president can do without majority support in congress. But despite its popularity, EPA regulatory authority has been under relentless attack from congressional Republicans and conservative judges and all the GOP candidates for president have promised to roll it back.

Politics is full of tradeoffs, but to Clinton (like Barack Obama before her) there actually is no tradeoff here. The right thing to do if you care about reducing greenhouse gas emissions is to maximize the Democratic Party’s odds of controlling the White House in order to deploy EPA regulatory levers. Taking an unpopular climate-related stance in pursuit of a policy goal that wouldn’t have a snowball’s chance in hell in congress is pointless and counterproductive.

Sanders has a lot of positions like this

If it were just carbon taxes, Sander’s issue positions probably wouldn’t be enough to outweigh his poll numbers in the eyes of most political insiders.

But Sanders — quite proudly and openly — takes these kind of stances on a wide range of issues. He markets himself in the primary, accurately, as the bolder, more politically courageous candidate.

While Clinton has clearly tried to signal sympathy with death penalty opponents and their concern about racial bias, Sanders outright calls for an end to executions.

While Clinton tries to reassure fracking opponents that she understands the need for tight regulations, but she also wants communities that like fracking to know she won’t stand in the way of their economic development — while Sanders promises a blanket ban.

Hillary Clinton proposes only relatively modest, overwhelmingly popular tweaks to the tax code while Sanders proposes to soak the rich to a much greater extent while also asking more of the middle class.

Hillary Clinton hews to the stale, politically safe orthodoxy on Israel policy while Sanders offers a breathe of fresh air.

Sanders is even willing to promise to let people who’ve already been deported from the United States back into the country if they have family living here.

On all of these topics you don’t need to question Sanders on the substance to see that it’s not a mystery why national Democrats rarely take these stances. They are not popular. Sometimes in life you have to do the right thing, whether it’s popular or not. But if you want to understand why the Democratic Party establishment is so skeptical of Sanders’ electability despite his strong current poll numbers this is why — Bernie Sanders says he is the candidate who is willing to take tough stands for progressive causes, and the establishment fears he is telling the truth.

Clinton’s vast experience is probably a weakness

The bad news for Clinton is that while her “try to take popular stances” theory of politics has a lot of merit, it clashes with another one of her perceived strengths — her decades of experience in national politics.

Sanders’ campaign has succeeded in making a fair amount of hay out of Clinton’s support for the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996 and of a crime bill in 1994 that featured many punitive elements.

From the vantage point of 2016, Clinton has tried to argue that DOMA was a bankshot effort to block a constitutional amendment barring gay marriage and that mass incarceration was a kind of unintended consequence of centrist Democrat policies in the 80s and 90s.

Neither account holds much water. The truth is much simpler: the Clinton administration signed DOMA and backed “tough on crime” policies because that stuff was very popular.

In line with her view that she ought to try to take popular positions, Clinton has shifted to the left on these issues as public opinion has shifted left. This is a sensible enough approach, and according to political scientist David Karol’s quantitative analysis in his book Party Position Change in American Politics it’s also fairly typical behavior. But it’s also saddled Clinton with a reputation as an opportunist. Someone who’s not “honest and trustworthy” as the pollsters say, and it ensures that when she changes her mind she is almost always covered (including by Vox) as doing so for opportunistic reasons.

The sweet spot in American politics is to be an opportunist without seeming to be an opportunist, which means inexperienced candidates generally have an advantage. Someone like Obama who bursts onto the national stage and then secures a national party nomination quickly can have all the up-to-date “correct” political opinions without the fuss and muss of a lot of flip-flopping.

But in 2016, Democrats are stuck choosing between two veteran politicians. One, Sanders, who has an unfortunate habit of taking positions that are too left-wing for public opinion and the other, Clinton, who has an unfortunately long record of trying to stick with public opinion even as it shifts.

The Trump opportunity

The good news for Democrats of all stripes is that the Republican Party is more likely than not to nominate Trump, who gives off every sign of being a disastrously weak general election candidate.

There are no sure things in politics, but both Democrats seem eminently capable of winning a race against Trump.

Progressive activists feeling the Bern fear, however, that it’s an opportunity Clinton’s small-c conservative instincts would squander. As Princeton University historian and Sanders supporter Matt Karp puts it, “virtually every significant and lasting progressive achievement of the past hundred years was achieved not by patient, responsible gradualism, but through brief flurries of bold action.”

Conversely, Democratic regulars worry that Sanders’ platform would make it harder to win key downballot races. Life is already hard out there for incumbent Democratic senators who need to run for reelection in states like North Dakota, West Virginia, and Indiana. House Democrats hoping for big Trump-powered gains know that means trying to run and win in districts that are three or four percentage points more Republican than the national average. Sanders’ new, more ideologically rigorous vision for the Democratic Party makes this harder at a time when Democrats are already struggling mightily in state and local politics.

More than “electability” per se, this is the question that truly marks the 2016 Democratic race. Is the main obstacle to progressive policy victories a lack of electoral victories against the Republican Party, in which case reduced ideological flexibility would do more harm than good? Or is the main problem that Democrats themselves, as Sanders says, are too compromised by ties to corporate interests and too hobbled by political cowardice? Younger people and liberals who self-identify as independents have tended to blame the Democratic establishment for its own shortcomings and choose the latter answer.

Bernie’s big ideas about politics

To an extent, Sanders’ thinking about the viability of his policy ideas is driven by a big-picture theory of politics that’s a bit outside the mainstream.

“If we had a media in this country that was really prepared to look at what the Republicans actually stood for rather than quoting every absurd remark of Donald Trump,” he’s said, then support for the GOP would entirely collapse. “this is a fringe party. It is a fringe party. Maybe they get 5, 10 percent of the vote.”

In his autobiography, Sanders writes that “one of the greatest crises in American society is that the ownership of the media is concentrated in fewer and fewer hands” which contributes to the dynamics he deplores.

Most Democrats think this is fundamentally mistaken. That the Americans who vote for the Republican Party do so because they are genuinely suspicious of big government, genuinely committed to individualistic values, or genuinely hostile to the interests of lower-income people (especially if they come from a different racial group) who would benefit from new programs.

They think that, historically, progress has been made when progressives have been willing to accommodate select aspects of conservatism — from FDR structuring Social Security to leave out most African-Americans to LBJ making Medicaid a state-run program to ObamaCare’s reliance on private providers this has been the way to win elections and get things done.

More than any particular stance on any particular issue, Sanders’ overall theory of politics worries most people who work in it professionally. Throwing out the traditional playbook is a risky move. A move Sanders may see as necessary to accomplish what needs to be done, but that inherently comes with a large downside and that Sanders has never really tested outside the context of an small, idiosyncratic rural state.