By Jacob Funk Kirkegaard (PIIE)

The campaign in Britain to “Leave” the European Union (EU) has lately turned on the issue of immigration in the United Kingdom (UK). This issue was always the Brexit advocates’ strongest political card, and their surge in the most recent polls is not so surprising. But the focus on immigration will likely only diminish the victory margin for “Remain” and also produce repercussions for the UK itself.

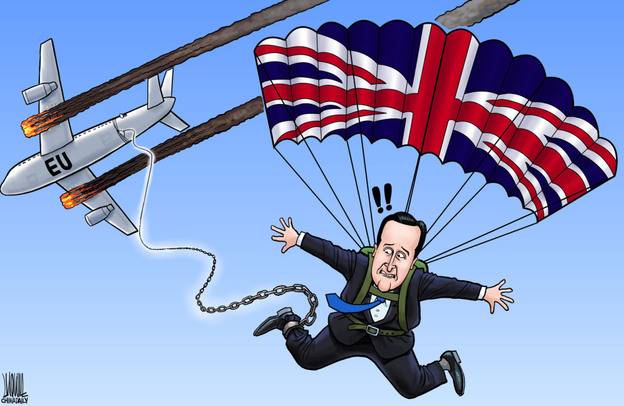

Prime Minister David Cameron was always going to be politically vulnerable to charges of not being able to control UK immigration. The 2015 Conservative Party election manifesto famously pledged to reduce net inward migration to below 100,000(link is external). Unfortunately for him, the latest data for 2015(link is external) indicated that a record 333,000 new migrants came to the UK last year (figure 1) and that almost half of them were from the EU (figure 2) and hence a direct function of EU, rather than UK, law.

As a result, Cameron’s political credibility is very weak, and the Leave Campaign has exploited that vulnerability, especially among the older voters.

The success of the Leave Campaign in turning this referendum into a yes or no to high levels of inward migration does make me raise my odds of a Brexit from the earlier very low probability of perhaps 10 to 15 percent. Immigration is an intense political issue and links directly to matters of identity that many voters may feel trumps any economic concerns arising from Brexit. I continue to believe, however, that the probability of Brexit is relatively low at maybe 20 percent. There are several reasons for that.

By doubling down on immigration, for example, the Leave Campaign has removed a lot of ambiguity about its plans for a post-Brexit UK. There is not going to be any “Norway option,” under which the UK would try to retain access to the Internal Market. As the example of Switzerland illustrates, such a move would require that the free movement of workers be maintained. Through its political promise to finally deal with immigration, the Leave Campaign has implicitly decided to pursue a clean break with the rest of the EU, damn the economic consequences.

It is equally clear that any post-Brexit scenario for national UK immigration policy will invariably mean shifting towards a much more restrictive overall policy. As indicated by various economic analyses of a post-Brexit UK economy, this scenario is invariably the most damaging to the longer-term UK growth outlook.

Financial markets are likely to watch this development with increased alarm, as not only polls tighten but also the downside risks from Brexit grow. One should therefore expect a material increase in financial market volatility of UK assets in the coming weeks, as a direct consequence of the Leave Campaign’s focus on immigration. As I have discussed before, such prereferendum market volatility will push voters toward the status quo option of Remain.

But the emergence of immigration as a crucial issue will have important implications in the likely event that Remain wins the referendum.

Immigration will clearly remain very potent political fuel for resentment on the right of UK politics for the foreseeable future, especially because a Remain victory will make it impossible for the UK to substantially reduce net migration levels. No one should therefore expect the demand to leave the EU “to take back control of our borders” to disappear inside the Conservative Party. The UK will thus remain an awkward partner for the rest of the EU, making calls for another referendum soon seem likely.

In addition, the successful mobilization potential of the immigration issue is likely to strengthen the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) even after a loss on June 23. The party could follow the pattern of Alternative for Germany (AfD), shifting from an economics-heavy agenda to a full-blown nativist right-wing anti-immigrant organization. Given the increasing fragmentation in UK politics, such a party could succeed in winning more seats in the UK parliament than the UKIP managed in 2015.

Finally, the referendum result is now likely to be tight, casting a shadow over Cameron’s political future in the face of a reenergized rightwing fringe of his own Conservative Party, as he will not likely be able to put the issue of “Europe” behind him and his party. Just how he can respond is unclear, but nothing is likely to satisfy that element. A leadership challenge to Cameron is thus more probable, even if he wins on June 23, though he should survive one.

In the end, the explicit playing of the immigration card by the leaders of any party with credible aspirations of governing is a dangerous political game in any country. The UK is no exception, particularly because the main alternative to the Conservatives in the UK Labour Party have themselves adopted a political platform so far to the left to make them unelectable. No matter what happens on June 23, the country will likely be more difficult to govern.