By Al Monitor

Around this time six years ago, Turkey was bracing for a referendum on controversial constitutional changes that would profoundly reshape the judiciary. To lure opposition voters, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) had put a sweetener into the package — an article to prosecute the leaders of the 1980 coup, which had victimized mostly leftist, Kurdish and some rightist quarters.

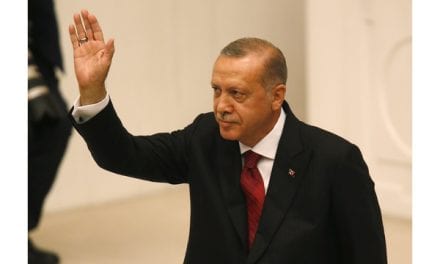

In a memorable episode in parliament ahead of the vote, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan broke into tears as he eulogized young people executed after the coup, and he read the farewell letter one of them had penned. “The referendum,” he said, “will be a score-settling with the mentality that sent young people to the gallows.”

Today, having survived a coup attempt himself, Erdogan is an ardent advocate of reinstating the death penalty. Consistency is hardly Erdogan’s strong suit, yet this turnabout is not just another one, for it threatens a full-blown crisis with the European Union and serious rifts at home.

No one has been executed in Turkey since 1984, first under a de facto moratorium and then legal reforms aimed to advance the country’s EU accession bid. Capital punishment was fully removed from the books in 2004, under Erdogan’s government, following two amendments in 2001 and 2002 that had narrowed its scope to terrorism and crimes committed during war.

Erdogan and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim say it’s the Turkish people who want the death penalty back after the July 15 coup attempt. Yet, talk in Ankara’s political corridors suggests otherwise. On July 16, hours after the putsch was suppressed, a group of AKP supporters were already calling for the death penalty at the parliament’s courtyard. “We want executions,” they chanted, as Yildirim emerged from an emergency session to condemn the putsch. Al-Monitor, however, has learned that AKP lawmakers began discussing the restitution of capital punishment while the putschists bombed parliament during the night. Moreover, the demonstrators were able to enter the parliament’s premises as guests of the AKP, which reinforces claims that the whole thing was orchestrated.

Top EU officials, including foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini, have issued stern warnings that reinstating the death penalty would end Turkey’s membership bid. Yildirim at one point cautioned against “rushing decisions in the heat of the moment,” though he asserted “the will of our citizens is an order for us.”

Erdogan, for his part, has urged parliament to take up the issue, pledging to readily approve any amendment to that effect. He reiterated his call even at the massive rally in Istanbul Aug. 7, which was meant as an unprecedented display of unity between the government and the opposition, including the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), a staunch opponent of the move.

Ertugrul Gunay, who served as Erdogan’s culture minister before resigning in disappointment in 2013, believes the president is using the threat of the death penalty to bully opponents and “bluff” the EU.

Gunay told Al-Monitor, “Erdogan is a pragmatist” with “no scruples about contradicting what he said yesterday. He knows very well that retroactive application of the death penalty [for the putschists] is legally impossible. So, why this turnabout? To spread fear in society, I believe. It is an intimidation intended for tomorrow, for the coming days.”

Gunay drew a link between the death penalty controversy and Erdogan’s efforts to overcome the crisis with Russia, which he described as a “great debacle” for Turkey. “The Russia move, along with the death penalty rhetoric, is a show for Europe — a message saying, ‘Look, I have the Russia option.’ [But] no European leader has correctly read the bluff.”

Turkey, Gunay argued, has too much to lose from severing ties with Europe or NATO, and closer bonds with Russia can never compensate for the loss. “A break is unlikely, so the bluff is aimed at the domestic public as well. Ties [with Europe] may become strained, but a break is something that neither Turkey’s economy nor military nor social fabric can afford,” he said.

Atilla Kart, a former lawmaker, warned of disastrous consequences if the death penalty was restored, stressing that a draconian crackdown was already underway against the Gulen community, which is held responsible for the putsch. “Today’s practices pale in comparison to the 1980 coup,” Kart, who had served as a lawyer for victims of the 1980 coup, told Al-Monitor. “They don’t even feel the need to trump up some evidence … acting [merely] with feelings of enmity and vengeance. [People are prosecuted] on the basis of lists sent directly to the courts, without any investigation by police and prosecutors.”

Kart recalled the massive sham trials that targeted mainly soldiers but also journalists and intellectuals several years ago, which the government first backed and then disowned as a Gulenist “setup” to weaken the military. “Can you imagine what a huge catastrophe it would have been if the death penalty was applied at the time?” he asked.

Metin Feyzioglu, the head of the Turkish Bar Association, told Al-Monitor that major legal obstacles stood in the way of reinstating the death penalty. Any such move will require not only adding a new article to the constitution, but also the removal of an existing one that gives precedence to international law with respect to human rights, and therefore Turkey’s withdrawal from related protocols of the European Convention of Human Rights. He said, “Even if you go that far, you still can’t apply the death penalty retroactively. And if you insist you can, you override a fundamental, 2,000-year-old principle of law, which means a total break with Europe and the rest of the world.”

Feyzioglu, too, believes the controversy was aimed at domestic consumption, but warns it impedes the extradition of coup plotters who managed to escape abroad.

Besides the CHP, the Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party is also opposed to the death penalty, which means an outright amendment in parliament is arithmetically impossible. Yet, with support from the Nationalist Action Party, the AKP could take the amendment to a popular referendum.

The government has not spoken of a referendum so far, and Yildirim keeps pledging commitment to the spirit of unity displayed at the Istanbul rally, in which the CHP is a key element.

CHP deputy chairman Bulent Tezcan told Al-Monitor the party would not back down from its opposition to capital punishment. He slammed the AKP for stirring popular sentiments “instead of promoting common sense,” but doubted it would actually submit a proposal in parliament. “If they do, that would be a sign of a serious descent into authoritarianism [and] break with the West,” he said. “But I don’t really think this is what they are aiming at, and hopefully, it won’t happen.”

“Hopefully” is the most oft-used word in Turkey these days, reflecting perhaps less hope and more apprehension on what lies down the road.