By Metin Gurcan

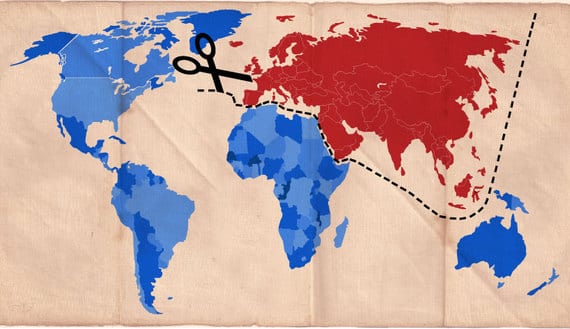

Turkey’s April 16 referendum enabled President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to launch a structural transformation in the state apparatus on his way to executive presidency. The fundamental question now is which direction Turkey will take in the coming period.

Erdogan’s first four foreign trips following the vote — all of them to the East — are indicative of a new orientation. After visiting India on April 30-May 1, Erdogan traveled to Sochi on May 3 for talks with Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin. He then visited Kuwait on May 8 before heading to China less than a week later to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping and attend a regional cooperation forum.

Summary⎙ Print The Eurasianist vision for Turkey has gone beyond rhetoric, gaining weight especially with regard to defense and security, but its proponents are themselves divided on what the country’s Eurasian future should mean.

In the meantime, Ankara took a severe blow from Washington. Overriding harsh Turkish objections, the administration made a decision to supply heavy weapons to the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units, without even waiting for Erdogan’s May 16 meeting with President Donald Trump.

Following Washington’s decision, the surging Eurasianist wave in Turkey has become even more pronounced. The Eurasianist perspective now seems to go beyond ephemeral discussions, gaining intellectual and institutional depth. The trend is likely to further intensify if Erdogan’s highly critical meeting with Trump and the May 25 NATO summit in Brussels result in great disappointment for Ankara. So what are the basic features and competing variants of this perspective?

It is important to keep in mind that the Eurasianist visions in Ankara do not originate solely from Erdogan. Over the years, they have gained prominence in the state bureaucracy, the security sector, think thanks and academia. Hence, Erdogan’s strategic foreign policy preferences are a necessary but not a sufficient condition to understand this perspective.

To start with, one should note that this rising trend is more apparent in terms of foreign policy, defense and security rather than economic and social life. Turkish think tanks such as the Anka Institute, 21st Century Turkey Institute, Center for Middle Eastern Strategic Studies, Turkish Asian Center for Strategic Studies and the Institute of Strategic Thinking have come to increasingly articulate the idea that the West is getting broken and it is time for Turkey to turn East.

The Eurasianist perspective rests on the following basic assumptions:

The world’s geo-economic and geostrategic center is increasingly shifting to the East, as “the rise of the rest” thesis argues, meaning that Turkey is becoming a center country.

The established West-dominated world order is no longer able to resolve global security problems.

Political and security integration with the West is dragging Turkey toward a new Treaty of Sevres, so Turkey’s two-century Westernization process needs a serious critical review.

West-centered international organizations such as the European Union, which ties Turkey’s hands in geo-economic terms, and NATO, which does the same in geostrategic terms, have plunged into structural crises.

The globalization process, from which the West benefits disproportionately, is creating huge inequalities, and Turkey is clearly becoming a front country in the clash between global capitalism and national state structures.

NATO, the United States and European countries have all come to erode the legitimacy of Turkey’s Syrian and Iraqi borders, withholding support for the country’s fight against terrorism. Since they no longer care about Turkey’s security concerns, Ankara needs to draw up its own strategic vision, relying on its own power.

The Eurasianist perspective has four distinct variants, which can be summarized as follows:

Pro-Russian Eurasianism: The main promoter of this variant is a community clustered around the small but vocal Homeland Party of Dogu Perincek, which functions as a virtual Russian lobby in the country. According to this community’s point of view, Turkey today needs an alliance with Russia, similar to the anti-imperialist collaboration with the Soviets in the days of Kemal Ataturk. Turkey, this community argues, should develop close cooperation with Russia, the natural leader of the Eurasian bloc, in the realms of foreign policy, defense and security. To achieve that, it needs to shrug off the NATO tutelage, which the Western defense bloc has imposed on Turkey, and get rid of American shackles on defense and security matters.

Pan-Turkic Eurasianism: This variant, which has an ultranationalist and irredentist outlook, rejects alliances not only with the West, but also with Russia, which it sees as a historic foe that can never be Turkey’s friend. According to their vision, Turkey needs a rapid opening to Central Asia to secure the support of the region’s Turkic republics and build an alliance based on common ethnic roots, which could be then expanded to the Middle East under Turkey’s leadership.

Islamist Eurasianism: The proponents of this vision, too, argue that Turkey needs neither the West nor Russia, but point to the country’s Ottoman and Islamic legacy as the alternative path. The argument goes that Turkey’s Ottoman past and Islamic identity dictate for it a global role, which it cannot escape and will have to assume, sooner or later. The proponents support a global ummah vision for Turkey, which, they believe, is the only country that can become the driving force of a new order of justice, especially in the Sunni world. A Turkey-led Sunni world, they argue, can balance both the West on the one hand and Russia and China on the other.

Erdoganist Eurasianism: In this variant, Erdogan’s charismatic leadership is seen as the main factor securing the continuity of the state and strengthening the bond between state and nation, especially since the failed coup attempt last year. Proponents of this thinking argue that the West is averse to Erdogan because he is a strong leader. Erdogan, they believe, can fix most problems of the East, especially in the Middle East region. Thanks to his leadership, Turkey has asserted itself on the global stage, threatening US and European interests. Erdogan’s leadership — described as “transformative” and “resting on moral ground” — is seen as a challenge and a rebellion against the West-centered global order, reflected best in his assertion that “the world is bigger than five.”

A common feature of the four Eurasianist visions is that they all stem from a reactive form of thinking, aimed at “thwarting the game of the West.” Thus, one can hardly say they have matured to proposing a new model for Turkey’s foreign policy and strategic vision.

Were Erdogan’s trips to India, Russia, Kuwait and China a message to the United States ahead of his meeting with Trump? Was Erdogan trying to show he has some strong trump cards? Or were the trips the sign of a genuine Eurasian drive? Is Turkey’s Eurasianist leaning driven by economic interests only, or does it signal a structural change in its foreign policy and strategic vision? And if Ankara is serious about a Eurasianist future, which of the four variants will ultimately prevail? How will the mounting power struggle between them affect the state apparatus? The first clues on these critical questions are likely to emerge in the coming weeks.