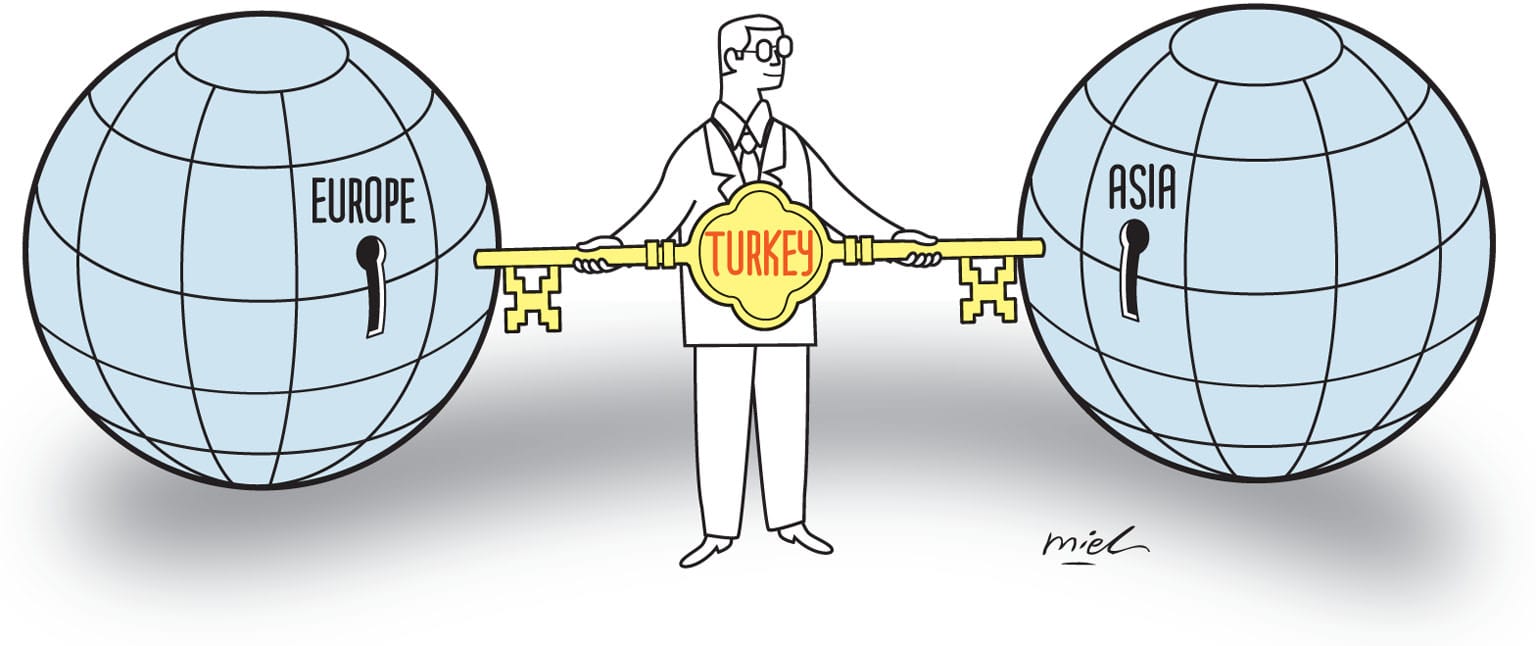

Ask Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim whether his country sees itself as Asian or European, and his studied response is to point out that while the Turks came from Central Asia, and their culture is Asian, they combine all this with European values.

As the 61-year-old former naval architect and engineer put it last Sunday in a 70-minute conversation, shortly after he landed in Singapore for a three-day visit, “We are both Asian and European. We are Eurasians”.

Just as well, perhaps. Who can begrudge the Turks their uniquely bicultural ways that make them feel as much at ease looking to the north-west, as looking east, which they have begun to do lately in some ways, including their endorsement of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

In fact, it is a bit of a homecoming because all but 3 per cent of Turkey’s land mass is in Asia and the Muslim-majority nation, in so many ways, has had much impact on this part of the world. In contemporary history, it would start from the time Turkey emerged as a beacon of hope to subjugated people when the Ottoman Empire crumbled after World War I and the country was liberated by the progressive-minded Mustafa Kemal Pasha in 1923.

The electric thrill this cousin to the West radiated at the time inspired many an anti-colonial leader out East. In Indonesia, Sukarno’s jousts with Mohammad Natsir over Turkey – the latter criticised Ataturk, or Father of the Turks, as “anti-religious” – is well documented. It is Asia’s good fortune that Sukarno prevailed and that his successors have kept the faith since. Richmond Wheeler’s The Modern Malay speaks of hundreds of young Malays up and down the peninsula buying portraits of Mustafa Kemal from Indian “mamak” shops. Former Pakistani military dictator Pervez Musharraf’s autobiography is laced with pages that suggest the general’s admiration for Turkey.

Today, the fundamentalist forces active in Indonesia are striving to overthrow a lot of what Sukarno left behind, including the Pancasila doctrine that is the ideological bedrock of the world’s largest Muslim nation.

The thought behind Pancasila was inspired in no small part by the secular legacy of the Ataturk, as Mustafa Kemal was known. It is a matter of comfort that, as the world battles the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and its dark version of an Islamic caliphate, Turkey, even as it faces its own stresses, nevertheless stands as a bulwark. It is not just Europe that benefits from this. Asia is a beneficiary as well.

“We’ve been very successful in our fight against Daesh,” said Mr Yildirim, using another name for ISIS. “Where most countries talk, we deliver results.”

This is true although it has been accomplished in a manner that not everyone would be comfortable with. By Mr Yildirim’s account, they include 4,000 ISIS activists “eliminated”, 4,000 jailed and 53,000 suspected activists and sympathisers deported.

Unpleasant as it might seem, this has often been the way of West Asia, where things started to come apart after the fall of strongmen like Saddam Hussein in Iraq, Muammar Gaddafi in Libya and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt.

Turkey, said Mr Yildirim, stands ready to share its experience and capabilities in fighting terrorism.

The sharing is bound to be welcomed in a region that’s feeling the reverberations of the conflict in West Asia.

From Indonesia to Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines, the authorities are battling ISIS’ doctrine at many levels. The movement has even been successful in capturing territory in the Philippines, where it is currently in a prolonged stand-off with the military in Marawi.

But it also is perhaps time for Turkey to see how some other Muslim-majority societies in Asia are coping with the pressure to drop their broad secularism in favour of a more prominent role for Islam in education and society that does not come in the way of their modernisation.

Next month Turkey introduces a new education curriculum in which the Darwinian theory of evolution will be controversially dropped from secondary school education. There also will be fewer classes studying Ataturk thought and more hours spent on religion.

While aware that this debate is not something restricted to Muslim countries – it has been a topic of discussion even in the so-called Bible Belt of the United States – Asia will be watching how the government negotiates this turn of the road.

UNEASY NEIGHBOURHOOD

Turkey has other good reasons to be looking East, as it were. Europe is not giving it the welcome it would have liked. While its members will not say this out publicly, the thought of a Muslim-majority state poised to overtake Germany in population size sits uneasily with them. Last year, the false scare of 75 million Turks showing up to look for jobs in Britain was cynically used by the pro-Brexit camp in their successful attempt to turn the referendum in its direction.

Since then an escalating feud between Turkey and Germany, Europe’s No. 1 economy, has worsened things. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Mr Yildirim’s free-spoken boss, has referred to German politicians as “enemies of Turkey”.

Mr Yildirim is candid to say that Turkey’s chances in that direction look dim. Besides, the EU demands that Turkey, which has some maritime issues with neighbours, sign on to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), something Ankara has declined to do because of its Aegean Sea dispute with Greece.

Turkey also could do with more friends in the world, given that its neighbourhood relations are not in the best of shape. In recent years, Turkey’s ties with Saudi Arabia and particularly, Egypt and Libya, have come under strain. Much of it is because of Mr Erdogan’s sympathies for the now-marginalised Muslim Brotherhood, which some suspect is also a ploy to play the pan-Islamic card to expand Turkish influence in the region, helped by a wink and a nod from Qatar. In fact, the Saudis demanded that Turkey close its military base in Qatar.

“The fact is, we offered to set up bases in both Saudi Arabia and Qatar,” Mr Yildirim said. “The Qataris moved forward on it, the Saudis neither rejected nor accepted. The base in Qatar will stay unless the Qataris ask us to move out.”

Mr Yildirim said portraying the Brotherhood as an extremist outfit is unfair and a mischaracterisation. Besides, in Egypt, the Brotherhood’s Mohammed Mursi, who won national leadership in June 2012 only to be ousted a year later by the military, had come to power after a democratic election.

“We are only supporting democracy and human rights, which are not protected in Egypt,” he said. “What wrong did Mursi do? Yet, the EU is silent on this. We cannot accept these double standards.”

Likewise, Turkey, while being a Nato member, has its own approach to Russia or Iran, declining to demonise either state. It takes a nuanced view of both nations and Mr Yildirim refers to Russia as a “reliable partner, especially in Syria”.

At the same time, he said, Turkey will resist both Shi’ite expansionism radiating from Iran and Salafi ideology promoted by Sunni Saudi Arabia.

The rest of Asia, particularly the Asean states, should have no quarrel with such thinking. Neither will South-east Asia, which has given Turkey sectoral dialogue partner status, hold its nose at Mr Erdogan’s attempts to consolidate power by moving to a presidential system – after all, this is a nation that has had 65 governments in 94 years.

The decent growth rates being clocked by the Turkish economy lately offer prospects for trade, tourism and investment to flow both ways. For instance, Singapore-Turkey trade is currently at a paltry US$1 billion (S$1.3 billion). The West Asian republic is also in the midst of a massive infrastructure drive, and a good part of it is centred on aviation. Ankara’s plans indicate it wants to take on Dubai as a hub for Asia and Africa to connect to Europe.

Still, to build further bridges to Asean it will probably need to modify its opposition to Unclos. The last thing Asean wants is another military power that says it has no belief in the efficacy of internationally established rules of the road, particularly in maritime affairs.