Sheri Berman is a professor of political science at Barnard College. She is the author of “The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe’s 20th Century.”

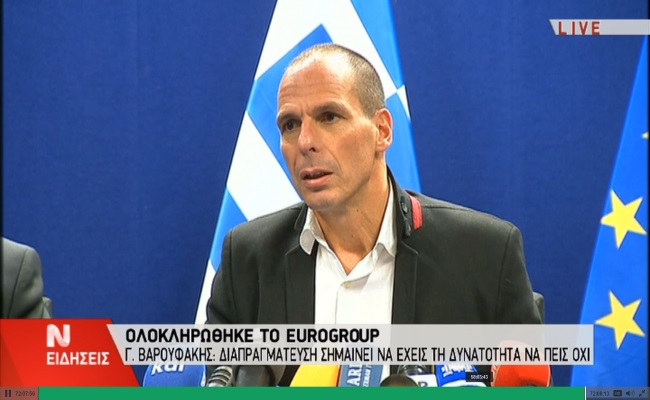

‘Adults in the Room” is hard to characterize. Ostensibly it is a nonfiction account by former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis of his negotiations with the Troika (the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund) over the Greek debt crisis. Sometimes, however, it reads like a novel centered on a globetrotting, motorcycle-riding hero fighting the forces of darkness and ignorance. Ultimately, perhaps it is best understood as the story of an academic idealist who became involved in deep political battles for which he had little understanding or sympathy.

The financial crisis left Greece bankrupt and in economic and social meltdown. In “Adults in the Room,” Varoufakis claims he had a plan that would have ended Greece’s suffering and revitalized Europe. Getting the Troika to accept it, however, would require threatening a Greek default, thereby potentially blowing up German and French banks (to which Greek debt was initially owed) and the euro zone itself. Varoufakis persuaded Greece’s new left-wing prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, to accept his plan, and Tsipras then asked Varoufakis to become finance minister to carry it out. Having previously been an academic and wary of politics, Varoufakis hesitated but in the end accepted — influenced by the pleas of a homeless man who urged him to “remember” the people and by the realization that “an historical accident had given [him] a rare chance to do right, speak truth to power, and work to bring a genuine recovery to our wasteland.”

Varoufakis thus headed off to save Greece and Europe — and was consistently and unceremoniously rebuffed. His plan called for Greece to trigger its nuclear option: its refusal to take on more debt, essentially ejecting itself from the euro zone. But Tsipras balked, and the whole thing came crashing down.

Much of “Adults in the Room” is taken up with Varoufakis’s explanation of this failure. Convinced of his plan’s economic and moral superiority, Varoufakis emphasizes his opponents’ stupidity and immorality. (He sees himself as the only adult in the room.) Key officials, including his nemesis, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, are characterized as pushing “incompetent authoritarism,” and their policies are seen as “organized folly” and “fiscal waterboarding.” Varoufakis claims that the Troika rejected his plan to avoid admitting that their own mistakes had aggravated the crisis and engaged in “lies and distortions that would make Joseph Goebbels proud.”

All good stories need a villain, and for Varoufakis, it’s the Germans. He alleges that their ultimate goal was enhancing their power, which meant crushing the leftist Greek government so as to not “give ideas to other Europeans.” Varoufakis has nothing but disdain for how the rest of Europe submitted meekly to its new “master.” (“Adults in the Room” catalogues the myriad people who agreed with him, but only in private.) The French come in for particular scorn for being unwilling to stand up to the Germans, not recognizing, Varoufakis claims, that German policy toward Greece was aimed at sending a message to Paris as well.

“Adults in the Room” provides, however, another interpretation of Varoufakis’s failure. Varoufakis approached negotiations as an academic, convinced that with facts and decency on his side, any argument could be won; he was unaware of and uninterested in the political calculations guiding his opponents. Varoufakis was a terrible diplomat — he had little understanding of protocol or power dynamics and treated Troika meetings like university seminars. He misunderstood (and clearly disliked) the Germans. Schäuble and the German government were committed to Europe; they just had a very different diagnosis of its problems than Varoufakis did. The Germans believed that the crisis was primarily caused by previous Greek governments’ corruption, irresponsible borrowing, and inability or unwillingness to collect taxes. They were therefore unwilling to allow debt restructuring to precede reforms; they believed that only the threat of bankrupting Greek banks and perhaps booting the country out of the euro zone would inspire the Greeks to do what was necessary. Greece’s own role in the crisis’s backstory occupies only a few pages of nearly 500 pages of text.

Germany’s position may have been wrong, but it was deeply believed and not only by Schäuble’s party, the Christian Democratic Union. Varoufakis does not recognize the political constraints facing the German government: Its taxpayers were loath to bail out a country seen as irresponsible and unwilling to accept the painful labor market and other reforms they themselves had endured.

Varoufakis’s explanation of his Greek allies is similarly apolitical, focusing on their weakness and corruption by the system. He is particularly stung by Tsipras’s betrayal; he believes that if Tsipras had stuck with him, his plan would have worked. But unlike Varoufakis, who took on the role of finance minister hesitantly and then constantly threatened to resign, as prime minister Tsipras was responsible for the fate of his country and party. Sticking to Varoufakis’s plan would have meant ejecting Greece from the euro zone into a world where its banks had no money and its survival depended on constructing an entirely new and untested payment system to replace the euro. Any strategy whose success depends on a prime minister sending his country careening off a cliff into the unknown is probably not a very good one.

It is hard to read “Adults in the Room” and not feel admiration for Varoufakis’s commitment to Greece and Europe, as well as frustration with his inability or unwillingness to play the messy and often irrational political games necessary to get his ideas a hearing. It is also hard to read this book and not feel immensely worried about Europe. During the crisis, the European Union pushed around democratically elected governments in Greece and elsewhere and insisted that the will of the people could not outweigh what it believed were necessary economic reforms. Varoufakis’s explanations of his failures may not be fully convincing, but his critiques of the E.U. are. If Europe is to survive, it will need to pay more attention to democrats and idealists like Varoufakis.