Erdogan is clashing with his predecessor, Abdullah Gul, as he continues to muddle relations with the U.S. and Europe

By Zvi Bar’el, Haaretz

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s angry reaction recently to his predecessor Abdullah Gul was to be expected, but it’s always fascinating to see how far Erdogan manages to stretch the limits of his venomous attacks. The bad blood between the two presidents is nothing new and has already been played out in public before. This time, though, Gul hit a sensitive spot, touching on what Erdogan defines as his war on terror.

According to emergency decree 696, published last month, any person who worked to suppress the military coup attempt in July 2016 – be they civilians, soldiers, policemen or government officials – would be granted immunity from prosecution for their actions.

Gul and human rights organizations claim that the vague wording of the decree could be interpreted to mean that even civilians who acted against the movement of Erdogan’s exiled rival, Fethullah Gulen, after the coup attempt (and not only during it) would also be granted immunity.

Gul, who last spring opposed the constitutional amendments granting Erdogan supreme powers, attacked the latest regulation and said it creates an opening to bypass the rule of law and grants civilians powers that are the exclusive right of the police and judicial system.

“It’s saddening that our former president is talking about vagueness. Where do you find vagueness? In which paragraph?” said Erdogan angrily. “And how have you suddenly boarded the ship of Kemal (Kılıcdaroglu, the opposition leader]?” he added, hinting at a betrayal of the party.

Gul and Erdogan were among the founders of the Justice and Development Party and worked together for years. Gul was prime minister during the first year of the party’s rule, until Erdogan took the position and rewarded Gul by helping to get him appointed president. But Gul didn’t agree with Erdogan’s takeover of state institutions and his mortal blow to the media. Erdogan, who has already proven that he doesn’t forgive his critics, has now targeted Gul, by accusing him not only of joining the opposition, but even of undermining the country’s efforts to fight terror.

Although Gul fought back, tweeting that he would continue to express his opinions, the only way he could really challenge Erdogan would be by running for president himself.

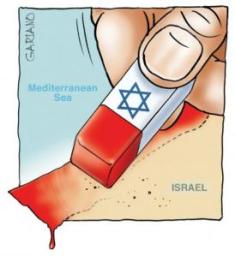

The relationship between Erdogan and Gul is very similar to the charged relationship between Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Reuven Rivlin, and according to a Turkish commentator in the daily newspaper Milliyet, “Erdogan has apparently adopted Israel as a model for political conduct, but in Israel you still have freedom of expression that we lack.” Anyone seeking additional examples can find them in the city of Adana, where the mayor ordered the removal of all signs in Arabic, “which cause visual pollution and damage the effort to protect the Turkish language.”

This political storm didn’t have time to develop because a far more threatening affair landed on Erdogan’s head, when on Friday a court in New York convicted the executive vice president of the Turkish state-owned Halkbank, Mehmet Hakan Atilla, of fraud and violating the sanctions against Iran – because he allowed Iranian-Turkish businessman Reza Zarrab to transfer gold to Iran in exchange for oil.

As far as Erdogan is concerned, what goes for Netanyahu goes for him – there is nothing, because there was nothing – since what was done, if it was done, fell within Turkey’s sovereign authority. Erdogan and his family have emerged clean in the affair until now, at least in the court proceedings. But the verdict, which is liable to lead to 30 years’ imprisonment for the bank vice president, can be used by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as a basis for imposing heavy fines, between $5 billion to $10 billion, on the Turkish bank. Such a fine would constitute a lethal blow to the entire Turkish banking system, and senior officials in Turkey hastened to promise that the government would come to the bank’s assistance.

Meanwhile, the affair has contributed to an additional deterioration in Turkey-U.S. relations, which began to decline as a result of the assistance that the United States provides to the Syrian Kurds, then slid further down the slope when U.S. President Donald Trump announced his recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, and now there are already those in Turkey who are proposing a severance of relations with the United States.

That isn’t a realistic demand, of course, but it attests to the uneasy atmosphere in Ankara and the feeling that Erdogan is taking his country far beyond the vision of the early years of his rule, when the slogan “Zero problems with neighbors” dictated his foreign policy. Now, not only have relations between the United States and Turkey reached an unprecedented low, but relations with the European Union are also in need of urgent orthopedic assistance to mend the fractures.

Last week Erdogan received a resounding slap in the face from French President Emmanuel Macron in regard to Turkey’s joining the EU. The current process “does not allow for an resolution in the coming years,” Macron said during a joint news conference with Erdogan, adding that he thought stringing Turkey along was hypocritical, in reference to the attacks on human rights in Turkey.

Erdogan made do with a chilly response: “We’re tired of knocking on the door of the European Union,” he said. But Turkey doesn’t have many other doors left to knock on.