With few independent outlets left, more journalists in Turkey now face jail time, fines, or getting fired for doing their job.

AYLA JEAN YACKLEY, The Atlantic

ISTANBUL—Pelin Ünker thought she had the scoop of a lifetime when Cumhuriyet, one of Turkey’s oldest newspapers, published her bombshell report that the family of Binali Yıldırım, then the country’s prime minister, owned vast offshore holdings. Yıldırım promptly admitted that the revelations were true—though he denied wrongdoing—and even invited an investigation into his two sons, who were named in the 2017 report.

That inquiry never materialized, and the authorities instead pursued Ünker, making her the first journalist in the world to be prosecuted for covering the Paradise Papers, a trove of some 13 million leaked documents that divulged tax loopholes used by the rich and powerful. A couple weeks ago, she was sentenced to more than 13 months in prison and fined $1,600 for insulting and defaming Yıldırım.

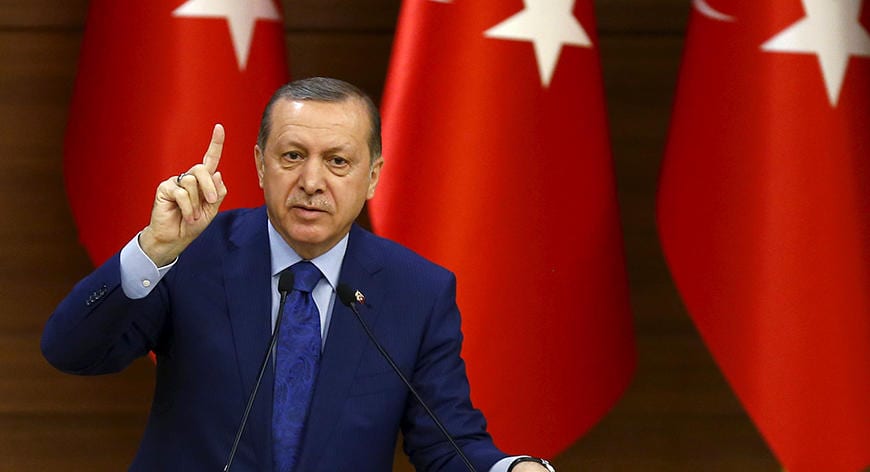

Ünker’s case exposes the perils of reporting in Turkey, where a sweeping crackdown has blunted civil society and turned the country into the world’s biggest jailer of journalists. Scores of media outlets that ran afoul of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government have been banned or forced to find new, more compliant owners. And even as Erdoğan grabs global headlines for denouncing Saudi Arabia over the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist killed in the kingdom’s Istanbul consulate in October, journalists in his own country labor under the threat of censorship, dismissal, or arrest.

Ünker was part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a global network that spent months sifting through the mass leak from a Bermuda law firm to lay bare the shadowy workings of the offshore financial industry. In her reporting, she found that Yıldırım’s sons had established shipping companies in Malta, which has a far lower corporate tax rate than Turkey, and had won a government contract back home. She also discovered that Serhat Albayrak—whose brother, Berat, is married to Erdoğan’s daughter—concealed offshore companies linked to the Turkish conglomerate the two Albayraks ran.

“My stories contained no slander, because the claims are not disputed, and not a single word of insult,” Ünker, 34, told me in a telephone interview after the verdict. “This sentence isn’t just about me. It’s punishing the act of journalism to intimidate others who might report this kind of news.”

Ünker can still count herself lucky. Should the appeals court uphold the verdict, Ünker is unlikely to serve more than a few days in jail, benefiting from a good behavior credit, her lawyer said. The judge ruled out a reprieve that would have eventually expunged her record, however, citing her propensity to commit the same “crime” again, Ünker and her lawyer said. Next time, she could wind up behind bars.

At least 68 of her peers, or more than a quarter of journalists jailed worldwide, are languishing in Turkish prisons, the Committee to Protect Journalists said last month. Other groups say that the figure is far higher; Human Rights Watch counts more than 175 journalists and media workers. The Turkish government says that it locks up those journalists who moonlight as terrorists or criminals. “It would never occur to us to discriminate by profession in these cases,” Erdoğan said last month. And to be sure, he has put away tens of thousands of people, including rights activists, politicians, and civil servants, most of them in a clampdown following a 2016 coup attempt against him. With a muzzled media and a cowed opposition, his drive to consolidate power has been largely unfettered. In June, Erdoğan—who first came to power in 2003—won election to a new supercharged presidency that puts most organs of the state under his control.

Almost 90 percent of Turkey’s news channels and papers are run by the government or businessmen close to it, according to Reporters Without Borders, which ranks Turkey 157th out of 180 nations in its World Press Freedom Index. Opposition voices have retreated to the web, but the long arm of the state extends there, too.

Necla Demir, the 29-year-old publisher of Gazete Karınca, faces up to 13 years in prison after prosecutors in Istanbul this month charged her with creating “terrorist propaganda” for the website’s coverage of a Turkish military offensive against Syrian Kurdish rebels in 2018. The indictment comes as Erdoğan threatens another incursion against the Kurdish militia, which has fought the Islamic State alongside U.S. soldiers, after President Donald Trump said that he’s withdrawing from Syria.

Turkey’s press has always worked within constraints, but enjoyed a brief heyday a decade ago, when Erdoğan needed its support to fight off the country’s secular old guard and champion a quixotic European Union membership bid.

Today, a trickle of mass-circulation newspapers still questions his authoritarian style of rule, but most outlets subscribe to an ardently nationalist view, giving short shrift to taboo topics such as Turkey’s conflict with the Kurds or human-rights abuses.

“There’s a suffocating climate of fear,” says Ahmet Şık, who spent 15 months in detention during his trial on terrorism charges, along with a dozen staff members from Cumhuriyet. “Cases are brought to stifle the handful of outlets writing critically of the administration, and the courts operate on government orders.”

Şık was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison in April for his coverage of alleged coup plotters and militant groups, but he remains free pending his appeal. A few months after his release, he quit journalism to run for parliament and won a seat with a left-wing opposition party. Nearly 30 of his colleagues at Cumhuriyet were sacked or resigned in September after a legal battle over management at the paper culminated in the appointment of a new chairman who had testified in court against Şık and his co-defendants.

Under its previous editors, Cumhuriyet was the sole Turkish outlet to collaborate on the Paradise Papers. When Ünker began working on the project, she would rush to the office in the middle of the night when a new batch of documents arrived, unable to contain her curiosity until morning. In the weeks after her son was born, she brought him to the newsroom so she could work on the story.

The disclosures about how global elites used offshore assets to reduce their tax burden led to a smattering of resignations around the world and calls for reform, at least outside of Turkey. Here, access to Ünker’s stories in Cumhuriyet’s online archives are blocked because of a court order.

“If our government officials and their relatives are hiding their wealth, the public ought to know,” Ünker said. “I never thought anyone would resign over this, but I did think the law, which calls for the disclosure and taxation of offshore accounts, would be applied—that just as regular citizens pay their taxes, the same would be expected of the rich.”

Her report had the opposite effect. When Yıldırım acknowledged that the companies existed and faced no repercussions, he normalized the practice. He became speaker of parliament after his post of prime minister was abolished, and is now running for mayor of Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city. Erdoğan named his son-in-law Berat Albayrak economy czar last year.

Ünker, meanwhile, quit Cumhuriyet after a decade at the paper to protest the new management. She now works as a freelance reporter for a German news organization, and is due back in court next month on defamation charges, this time against the Albayrak brothers. Another prison sentence looms.