By Ahval

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has deeply embraced populist rhetoric during his time as the country’s leader, remaking the country during his 16-year reign, U.K. news outlet The Guardian reported on Monday.

Erdoğan’s four-month spell in prison in the late 1990s for reciting an Islamist poem was a formative experience, according the Guardian. “He emerged with an acute sense of the power of the spoken word and a sharpened resentment toward the elites who openly ridiculed his piety, mocked his working-class background and sought to exile him from the political establishment,” said The Guardian. “Two decades later, the Turkish president is a populist colossus.”

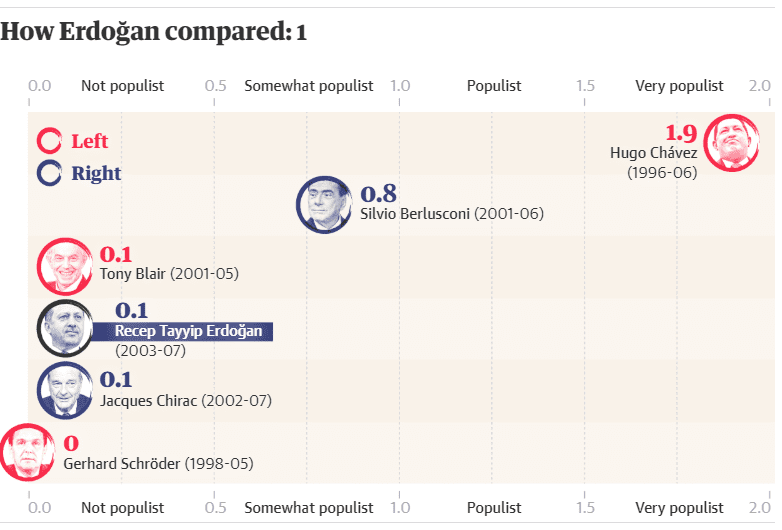

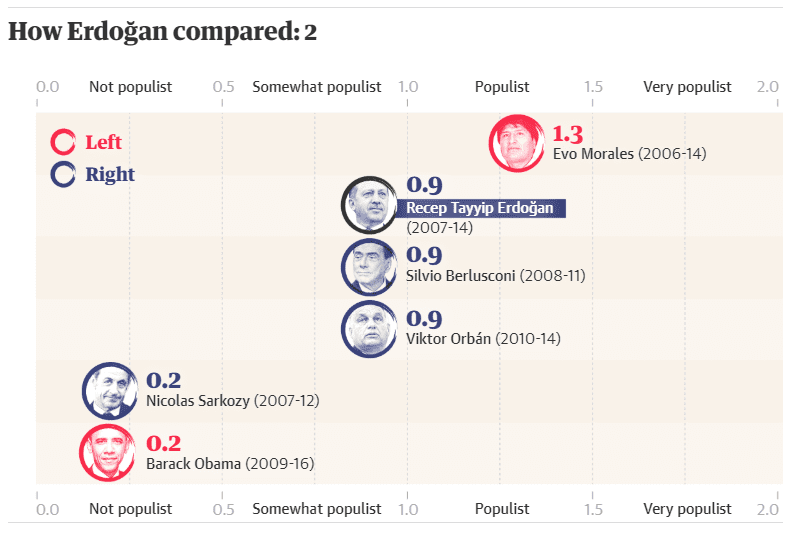

His most recent term in office was the most populist of any right-wing leader in the Global Populism Database, which tracks populist discourse in the speeches of almost 140 leaders in Europe and the Americas.

“Erdoğan is the inventor of 21st century populism,” said Soner Çağaptay, author of The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey. “His career shows the extraordinary effect one person can have on an entire country.”

Since taking power in 2003, Erdoğan has transformed from a cautious reformist seeking entry to the European Union (EU) to an authoritarian whose speeches are as populist as those of the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez.

He was born and raised in Istanbul’s low-income Kasımpaşa neighbourhood, where so-called “black Turks” — conservative, working-to-middle class citizens — now see him as an inspiration. “He changed everything,” a barbershop owner told The Guardian.

His speeches during his first term in office were mostly devoid of populist discourse, putting him in the same category as British Prime Minister Tony Blair. He almost sounded like a liberal, respectful of democratic norms and minority rights. “We won’t let democratic progress slide,” Erdoğan said in the mainly Kurdish city of Diyarbakır in 2005.

His more recent terms show a more confident politician, skilled at manipulating the state apparatus, according to The Guardian.

“It was Erdoğan’s commitment to elevating Turkey into the club of European nations that gave him cover to dismantle the constitutional checks on his power,” said the Guardian. “To bolster Turkey’s EU bid, parliament helped the prime minister neuter the powerful military, passing laws subjecting it to civilian control.”

Constitutional changes put in place in 2007 and 2010 ensured women’s and workers’ rights, while consolidating AKP power and deepening religious conservatism, said the Guardian.

“Erdoğan was like a doner kebab master,” Çağaptay said. “He lured us in, and then worked steadily and methodically, taking just thin slices off Turkish democracy at a time, removing a layer of liberal, secular Turkey every time he could.”

Erdoğan soon began to employ a more bellicose stance toward his opponents, in the military, on the streets, and in the news media. After a big AKP win in 2011, he stood on the balcony party of AKP headquarters in Ankara and declared: “The tyranny of the elites is over” adding that Turkey would no longer be ruled by those who split from God’s will.

“That line, fusing the will of God and the will of the people, seemed to enshrine Erdoğan’s emerging brand of Islamic, nationalist populism,” said the Guardian.

Erdoğan’s animosity toward his enemies was deepening during this time. Angered by the European Court of Human Rights’ 2005 decision to uphold the French ban on Muslim face veils, Erdoğan was increasingly doubtful Turkey had a future in the EU, according to the Guardian. He soon called for the restructuring of the United Nations and stormed out of a 2009 Davos debate about Gaza with Israeli President Shimon Peres.

Then came his aggressive response to the Gezi Park protests of 2013, with 22 people killed in the crackdown and 5,000 arrested. “It was a foretaste of the most recent – and most populist chapter – of Erdoğan’s leadership, which began when he was elected president in 2014,” said the Guardian.

Erdoğan’s speeches since he assumed the presidency, particularly after an attempted coup in 2016, have been his most consistently populist of his career, sharpening his fury at perceived enemies at home and abroad.

Yet he remains deeply popular, despite the two-year state of emergency imposed after the failed coup and the more than 160,000 members of the judiciary, academics, teachers and civil servants who lost their job in post-coup attempt purges.

“He stands by the poor, people who have been hit hard by fate,” a tea farmer in the Black Sea town of Rize told the Guardian. “Our hearts are with him. The most important thing is that he stays strong to protect Turkey.”