The NATO allies’ partnership has devolved into a “slow-motion car crash.”

By Alex Ward, VOX

The United States and one of its longtime NATO allies, Turkey, are suffering a complete breakdown in their relationship — and it’s unclear if it will ever recover.

Though Turkey and the US have a long history of partnership (including years of fending off the Soviets together), Ankara’s recent actions have blown a hole in the center of their alliance.

The country, for example, is openly defying US wishes on a Russian-made weapons purchase. Ankara has also blamed a US-based cleric for orchestrating a coup against the government, although there’s no evidence to support the claim. It has held American hostages for years. And Turkey even attacked US allies in Syria, throwing the anti-ISIS campaign at the time into chaos.

Their crumbling partnership is, perhaps, not a complete surprise — despite being NATO allies for seven decades, the US and Turkey have often disagreed on foreign policy, particularly toward the Middle East. One reason is that Ankara is perennially skeptical that Washington takes its security concerns seriously, says Amanda Sloat, a Turkey expert at the Brookings Institution think tank in Washington, DC.

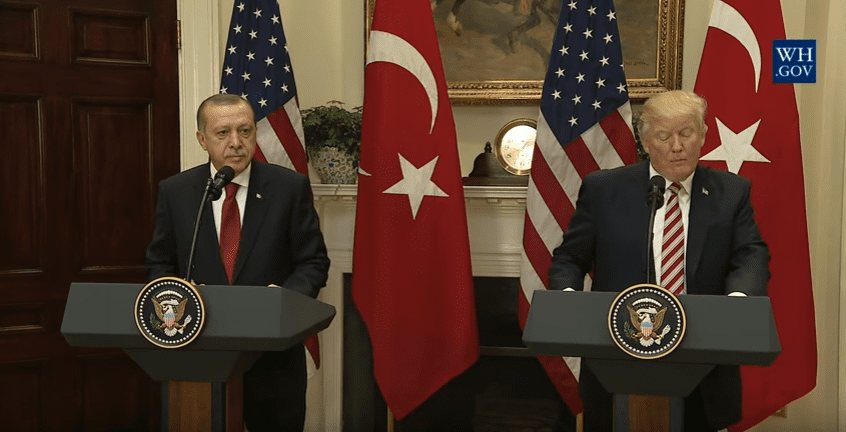

The US, Sloat added, worries about Turkey’s growing friendship with Russia and acceleration away from democracy. That’s been exacerbated by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, an authoritarian who has dismantled secular liberal politics in favor of Islamist political values, harbors anti-Western views, and has widened the US-Turkey gap.

The Trump administration has also played a role in the breakdown of ties. Trump placed tough sanctions on Turkey last August, and at one point vowed to “devastate” the country’s economy.

However, the over half-dozen Turkey experts I spoke to for this piece unanimously said that the reason why the US-Turkish relationship is likely doomed for the foreseeable future is mostly because of Ankara.

“This is no longer anything that can accurately be called a strategic partnership,” Lisel Hintz, a Turkey expert at Johns Hopkins University, told me. “I wouldn’t even call Turkey an ally. An ally doesn’t behave the way in which Turkey has been behaving.”

This swift breakdown in ties is bound to have wide-ranging consequences. As a result of losing a friend (or, for some “frenemy”) in the region, the US will surely find its goals in Europe and the Middle East harder to achieve over the coming years.

“This is a slow-motion car crash,” says Aaron Stein, a Turkey expert at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia.

The US and Turkey were never perfect partners

The history of US-Turkey relations is, at best, a rocky one. “There probably never was a good old days,” says Howard Eissenstat, a Turkey expert at the Project on Middle East Democracy think tank in Washington.

Turkey joined NATO in 1951, at which point both countries worked together to counter the Soviet Union during the Cold War. America and its other allies focused more on threats to Western Europe, leaving Turkey to act as the heavily armed bulwark against Moscow’s advances in the Middle East, and particularly the Black Sea.

That didn’t make the two countries the best of friends, though.

In 1963, for example, then-President Lyndon Johnson warned Turkey in a letter against invading Cyprus, the small island nation in the Mediterranean. Between 1963 and 1964, fighting between Turkish and Greek Cypriots increased after Cyprus’s president made constitutional changes perceived to benefit Greek Cypriots.

The US president’s letter was perceived as a major insult to Turkey.

“Johnson’s letter has done more to set back United States Turkish relations than any other single act,” a CIA officer wrote in a once-secret June 1964 cable. The letter “illustrates that the United States has not understood and still does not understand Turkish intensions or positions on Cyprus” and “makes it almost mandatory for Turkey to become more independent of the United States in the field of international relations.”

A month later, when the Greek government backed a military coup on the island, Turkey went ahead with the invasion. To this day, Cyprus remains a divided country where a Turkish-Cypriot government controls the northern third and a Greek-Cypriot government controls the rest.

Experts say Ankara never really felt like Washington had its back throughout the Cold War. Nonetheless, they remained allies, banded together by their mutual Soviet concerns.

But then two events happened that changed all that.

The first, of course, is that the Cold War ended, exposing the deep fissures masked by their mutual anti-communist stances. The second event, putting those relationship cracks on full display, was the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War.

After the US military kicked out Iraqi forces from Kuwait, then-President George H.W. Bushworried about Baghdad’s repression of the Kurdish people in the north of Iraq. America therefore imposed a no-fly zone — meaning warplanes couldn’t operate in a defined airspace without the threat of retribution — over that part of the country.

While it did protect thousand of Kurds from slaughter, the Kurds also decided during this time to push for their own state — Kurdistan — within Iraq.

That was something the Turks strongly opposed. Ankara has been fighting a decades-long insurgency of Kurdish separatists inside Turkey, and thus considers growing Kurdish power to be a security problem. And yet here was the US, providing military cover while the Kurds aimed to establish their own government near Turkey’s southeastern border.

Considering all of this, former Turkish parliamentarian Aykan Erdemir told me, “it’s naive to assume this relationship has always been harmonious.”

But lately, it’s gotten worse. Much worse.

The current US-Turkey dispute, explained

Burak Kadercan, a Turkey expert at the US Naval War College, says the current problems between Washington and Ankara should be thought about in three separate ways.

First, there are just some intractable issues neither side is likely to solve soon. Second, there are long-term problems they might fix over time. And third, some new concerns have popped up that probably will bedevil the relationship for a while.

Let’s take each in turn.

The Kurds and the war on ISIS

The US and Turkey have quarreled over the Kurds, a Middle Eastern ethnic group, in years past. But the conflict in Syria showed that the disagreement persists — and remains deadly.

After a 2011 uprising in Syria against the government devolved into full-blown civil war, ISIS fighters seeking to establish a fundamental Islamist caliphate took advantage of the chaos and swept in, taking control of large swathes of the country. The US saw this as a threat to regional security, and decided to militarily push back.

In order to defeat ISIS, Washington allied for years with Kurdish fighters who toiled on the ground while the US-led coalition mainly dropped bombs from the sky. As they rooted the terrorist organization out from northern parts of Syria, Kurdish forces — which were known as the People’s Protection Units (YPG), before they joined with other fighters and became the amorphous Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) — took control of the territory.

Turkey was never happy about the US-YPG partnership to begin with. Ankara, rightfully, according to some experts, complained that the Syrian Kurds had close ideological ties to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, a terrorist organization. That Turkish Kurdish group has waged a bloody fight for autonomy from Turkey since the late 1970s.

But when the Trump administration helped them acquire territory in Syria’s north — which borders Turkey’s south — it proved a step too far for Ankara.

Erdoğan responded by sending Turkish troops into northern Syria to fight Kurdish forces in January of last year, throwing the US-led anti-ISIS campaign in jeopardy.

“Turkey will suffocate this terror army before it’s born,” Erdoğan said on January 14.

It was a development that US military personnel didn’t anticipate early on, Eissenstat, who is also a St. Lawrence University professor, told me.

As the anti-ISIS fight began, he gave lectures to troops and staff about what to expect. “I basically said ‘you’re not going to get Turkey to support the YPG in any way against ISIS.’ And they were flabbergasted. They didn’t believe me,” he said.

Here’s why they should have: “For Turkey, groups like ISIS are fundamentally security problems,” he continued. “The YPG is an existential one.”

This fundamental misunderstanding is ruining President Donald Trump’s own war plans now.

Trump has said that he wants to withdraw US troops from Syria, but his advisers warned that Turkey would likely launch a full-scale invasion to rid the Kurds from northern Syria. Washington, then, seeks Ankara’s guarantee that it won’t attack America’s allies there if US troops come home.

During a trip to Israel in January, National Security Adviser John Bolton reiterated that point. “We don’t think the Turks ought to undertake military action that’s not fully coordinated with and agreed to by the United States, at a minimum so they don’t endanger our troops,” Boltontold reporters in Jerusalem, referring to the roughly 2,000 US troops in the area advising the Kurdish fighters.

The top Trump aide then traveled to Ankara to meet with Turkish officials, including Erdoğan. But the Turkish leader chose not to meet with Bolton, even though he was in the capital, because of those remarks. “It is not possible for us to swallow the message Bolton gave from Israel,” he told his parliament.

Without a guarantee for the Kurds’ safety, and to fight off any ISIS remnants, Trump has reportedly decided to keep around 1,000 troops in Syria.

Experts told me that unless the US begins to consider the Kurds as much of a threat as Turkey does — or Turkey stops worrying about the Kurds, a very unlikely prospect — both countries will continue to squabble over this issue indefinitely.

“This is not a problem that can be talked away,” Kadercan told me. “It’s still going to be there with or without Erdoğan.”

Erdoğan’s authoritarianism, Gülen, and imprisonments

There’s no denying, though, that Erdoğan’s disdain for democracy is a major impediment to improved US-Turkish ties.

Erdoğan has held power in Turkey for 16 years — first as the country’s prime minister from 2003 to 2014, and then as president. And he has also seemingly stopped at nothing to preserve his authority: He has silenced his challengers, jailed dozens of journalists, and changed the Turkish constitution to favor him.

But his drive for absolute control intensified in July 2016 when Erdoğan survived a failed military coup that attempted to oust him out of power.

A faction of the Turkish military, claiming to speak for the entire Turkish Armed Forces, aimed to oust Erdoğan in the name of democracy — despite the fact that Erdoğan and his party were democratically elected. But the attempt failed, mainly because large portions of the military sided with their president.

Erdoğan used his triumph as an excuse to purge the military and government of people he suspected of plotting against him, thereby creating a state more subservient and pliable to his will.

Indeed, Turkey’s presidency used to be a primarily ceremonial role, while the country was mainly ruled by a prime minister in a parliamentary democracy. But that changed in 2017, when a referendum led by Erdoğan’s party overturned the existing government structure. This abolished the prime minister’s role and cleared the way for Erdoğan to extend the limits of his authority.

Unchecked, he began to openly criticize the US with language that veered into outright hostility.

Erdoğan, without evidence, blames a Turkish cleric named Fethullah Gülen for instigating a July 2016 coup attempt and has called for his immediate return to Turkey to stand trial. The problem for Erdoğan is that Gülen currently lives in Pennsylvania after coming to the US in 1999 to escape persecution from a previous Turkish administration. Trump, like other presidents before him, has so far refused to hand the cleric over to Ankara.

The Gülen rift grew bigger during the White House’s push to get Andrew Brunson, a US pastor, released from Turkish prison in 2018.

Ankara charged Brunson with unproven crimes and claimed that he was involved in terrorism. Trump was personally invested in bringing Brunson home, going so far as to impose heavy tariffs on Turkey last August until he secured the pastor’s release. That was a major move, especially since Turkey is America’s fifth-largest source of exports.

The sanctions hurt Ankara’s economy so badly that its currency, the lira, plunged to a record low against the dollar last year.

But experts mostly agree that Erdoğan originally aimed to withstand the American-imposed pressure out of hope the US would trade Gülen for Brunson. That didn’t happen, but both sides did reach a secret deal that led Turkey to release Brunson, who returned to the US last October.

The pastor’s detention, though, is just one example of a growing problem in Turkey. Ankara has also detained three Turkish citizens (two were put in prison, and one was placed under house arrest) that work for the State Department. The charges again them, by all accounts, are bogus.

Experts I spoke to said that jailing US government employees is not normal diplomatic practice, and it’s especially egregious when a NATO ally does it.

And Erdoğan’s rhetoric during local elections last week stoked anti-American sentiment among his base throughout the campaign. There has long been anti-US feeling within the Turkish government and public — partly because of rampant conspiracy theories about America secretly plotting to crush Turkey, and Washington’s much-disliked Middle East policies — but the autocrat ratcheted up the language to a whole new level.

“What’s unique now is that even when US-Turkish relations were turbulent, there was never such a systematic attempt to smear the US from the highest levels of the Turkish government or state-run media,” Erdimir, who is now at the conservative Foundation for the Defense of Democracies think tank, told me. “There has never been this level of conspiracy theories spread by government circles or such a level of threat against US officials and troops.”

When it comes to big-picture Washington-Ankara relations, all of these problems are solvable.

For one, Erdoğan’s party lost local elections in Ankara and Istanbul last week, making it clear that the autocrat’s power isn’t absolute. There’s a chance, although a very small one, that he loosens his grip on the state and enacts some democratic reforms in light of these results.

The Gülen dispute and the jailing of US government employees are very bad for the relationship between the two countries, but it’s possible that sustained diplomacy behind the scenes can smooth things over.

However, new issues keep popping up that threaten to further derail the fragile alliance.

Russia and the S-400 missile-defense system

The latest conflict roiling Washington and Ankara is over an anti-aircraft missile system — one that Russia wants to sell to Turkey.

The Turkish government has pushed hard to get one for years because it’s one of the nation’s biggest defense gaps. The system would make it much better at shooting down threatening planes.

Some experts say Ankara especially wants it now because the 2016 coup attempt included rogue military pilots flying fighter jets with the intention of ousting Erdoğan. Such a system could help the president shoot down potential coup-plotting airmen in the future.

The United States and some European countries, as NATO allies, assumed Turkey would buy the platform from one of them. After all, they say, a US or European-made system would work more seamlessly with NATO militaries because they use similar software, radars, and even troops to provide maintenance.

But Turkey looked elsewhere, specifically toward China and Russia.

In 2013, Ankara initially said it agreed to purchase a Beijing-made system before changing its mind. That once again opened the competition to the US and European models. But in a somewhat surprising move, Turkey then agreed to buy Russia’s S-400 system in 2017 for $2.5 billion.

The Trump administration isn’t happy about this at all, and US Army general and NATO Commander Curtis Scaparrotti told the Senate in March as much.

“I would hope that they reconsider this one decision on S-400,” he said. “My best military advice would be that we don’t then follow through with the F-35, flying it, or working with an ally that is working with Russian systems, particularly air defense systems, with one of our most advanced technological capabilities.”

Experts tell me the US fears that the Russian system could pose a threat to the 100 US-made F-35 fighter jets that Turkey purchased, partly because the system’s radar could potentially collect intelligence from the plane and send it back to Russian spies. That worry is a bit overblown, though, especially since F-35s already fly near China, for example.

Still, there’s enough fear that the top Republicans and Democrats on the Senate foreign relations and armed services committees wrote a New York Times op-ed on Tuesday to warn Turkey against buying Russia’s system.

“By the end of the year, Turkey will have either [US-made] F-35 advanced fighter aircraft on its soil or a Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile defense system,” four senators wrote. “It will not have both.” They also noted that Turkey risks being kicking out of the F-35 production program, which provides jobs and roughly $12 billion to its economy.

But Turkey won’t relent, as Erdoğan made clear on Monday. “We have determined our road map for the S-400,” he said shortly after meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow. “No one can expect us to give up this.”

Russia plans to start delivery of the system in July and turn it on in October. As a result, the US this week announced that it would block necessary equipment to operate the F-35unless it cancels the Russian order.

What’s more, Turkey’s installation of the program would trigger the US to place more sanctions on the country. A bill called the “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act” requires the US to impose penalties on those that do business with Russia’s defense sector.

“Sanctions will hit Turkey’s economy hard — rattling international markets, scaring away foreign direct investment and crippling Turkey’s aerospace and defense industry,” the bipartisan group of senators wrote.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has effectively turned this issue into a referendum on Turkey’s relationship with NATO writ large, and America and particular.

“Turkey must choose,” Vice President Mike Pence said on April 3 during the NATO anniversary celebration in Washington. “Does it want to remain a critical partner in the most successful military alliance in history, or does it want to risk the security of that partnership by making such reckless decisions that undermine our alliance?”

Based on recent history, it doesn’t seem like the US will like the answer to that question.

How the US and Turkey are managing their “divorce”

The natural query now is: Will the US-Turkish relationship improve? It’s unlikely to any time soon, experts say.

Three main factors help explain why.

First, as the Russian missile defense system kerfuffle shows, Erdoğan has started to turn more toward Moscow than toward Washington. Indeed, the Turkish leader and Putin met in person seven times in 2018 and spoke on the phone another 18 times that year, indicating a developing, close relationship.

While Turkey remains in NATO (and no expert says it will leave any time soon), closer Turkey-Russia ties will naturally strain Ankara’s relationship with its allies — particularly the US. But there is some positive news, says Johns Hopkins’ Hintz: “Turkey will never trust Russia the way it does institutions like NATO,” because it “still benefits from the military alliance.”

So there may not be a complete US-Turkey break on this front, though it will likely remain a major stressor.

Second, Erdoğan shows no real sign of ending his anti-American stance. He still promotes conspiracy theories against the US and openly blames the country for many of Turkey’s woes. He’s accelerated democratic backsliding, and his government still poses a threat to American citizens, journalists, and government officials.

Trump, for his part, hasn’t done much to quell tensions — he’s sanctioned Turkey and placed tariffs on products, as well as openly lambasted Ankara for detaining US hostages. As if to feed the conspiracy theories, at one point Trump vowed to “devastate”Turkey’s economy if it attacked the Kurds in Syria.

But Washington’s need for Ankara has declined over time. Incirlik Air Base, a US Air Force base in Turkey’s south, proved indispensable to US and NATO operations in the Middle East for years. But the base is no longer as valuable to its Western allies — and part of that is Turkey’s fault.

In 2017, German troops left the base after Erdoğan’s government wouldn’t let lawmakers from Berlin visit their troops. And on multiple occasions, Ankara used the base as leverage against the US in discussions over how to conduct the anti-ISIS war.

Washington doesn’t have to put up with that as much anymore, experts say, especially since there are new bases nearby in Qatar or Romania that could become roughly, although not entirely, as useful.

One way ties could improve in the short-term is if the US decides to help Ankara’s struggling economy recover, Jenny White, a Turkey expert at the University of Stockholm in Sweden, told me. But she’s also skeptical that could happen, mainly because “nothing can be fixed unless there’s a diplomatic message to reach a solution — and that’s not happening right now.”

So what to make of the US-Turkey fallout, going forward? Eissenstat offered the smallest of silver linings. The reason the relationship is so fraught now isn’t because both countries are enemies, but rather because the two historical allies are separating after so long.

“The United States and Turkey will continue to have close areas of cooperation,” he said, “but they’re going through a divorce. And there’s lots of countries that we don’t get along with that nonetheless we’re capable of cooperating with, but there’s a lot of bitterness that goes with divorces.”

And as this divorce happens, America’s ability to work with Turkey in the Middle East and Europe will continue to dwindle — meaning US influence there, at least somewhat, degrades.